We are in very troubled times. This story started many scores ago and was penned by the founding fathers, many of whom may have known of the toxic contradictions that would poison the future of this great land. From a failed Reconstruction, a compromised Civil Rights Movement and a thwarted Black Power Movement to silenced affirmation action and the countless lynchings, occurrences of police brutality and instances of injustices in between, we see the consistent resistance to social respect and justice. We are in haunted times, where race and blackness are debated and presented like magic, tricking our best minds to think we are in a post-racial fantasy. We are…

We are in very troubled times. This story started many scores ago and was penned by the founding fathers, many of whom may have known of the toxic contradictions that would poison the future of this great land. From a failed Reconstruction, a compromised Civil Rights Movement and a thwarted Black Power Movement to silenced affirmation action and the countless lynchings, occurrences of police brutality and instances of injustices in between, we see the consistent resistance to social respect and justice. We are in haunted times, where race and blackness are debated and presented like magic, tricking our best minds to think we are in a post-racial fantasy. We are in war times, where racial deflection and white supremacy and privilege are on one side, and black poverty, mass incarceration and double-consciousness are on the other. Welcome to The American Civil War II, the war that started way before General Lee was born.

American history is a very complicated story, where the wounds of the Civil War continue to sting even after 150 years, along the lines of geography, race and regional heritage, compromising national healing and sometimes, civility. This tension played out loudly in the late 1990s in South Carolina over the placement of the Confederate flag on the capitol dome. The mass demonstrations and counter-demonstrations across the South showed the gigantic rift in the reading of the Civil War and its associated stories, and how greatly divided we really are as a country and how this war continues.

And with any war, flags are very important signifiers that mark the social, cultural and historical space. While some may believe the Confederate flag is about heritage and not hate, the reality speaks otherwise. This flag can never represent the rich diversity and dynamic heritage of southern folk, where the African-American experience has played a central role. And to continue to fly this flag is not only passive-aggressive and disrespectful, but promotes visual terrorism. And if black people and sympathetic others are not in constant resistance and protest of such symbols, then we run the risk of sending the wrong signal — that everything is fine and that we don’t matter. So we protest.

My protest started by recoloring the Confederate flag black, red and green — the colors of black nationalism. This was my way of arresting my own anxiety and fear of black erasure, both personal and collective. Also it was the beginning of a political art journey, starting with me showing the recolored flag in a Soho gallery, then Harlem with more variations, then bringing the AfroBattle flag to a KKK rally in Florida, where I realized the great social impact of going beyond the safe walls of the gallery space and how art can shape and inform what can matter most — identity and its relationship to symbols and community.

In 2004, I was invited to bring my work to Gettysburg, where I knew this would be a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to bring the artist voice to a very sensitive subject and to the national stage from one of the most important battlegrounds in American history. And so the project Recoloration Proclamation was born — an exhibition featuring the installation, “The Proper Way to Hang a Confederate Flag” — a Confederate flag hanging from a 13-foot gallows. The plan was to have the gallows installation up outside for the duration of the exhibition, following with a “funeral procession” for the flag to the black Union cemetery for “burial.”

This never happened. Once the Sons of Confederate Veterans (SCV) became aware of the exhibition, the politics around the exhibition shifted drastically, creating a direct collision between security issues and free speech. I received death threats. The forceful counter, lead by the SCV, resulted in the work not being allowed to be presented as an outdoor installation as previously planned. This created a crisis in which I had to measure the weight of my work being compromised with the reality of American cultural politics. So in the end, I decided to do a smaller indoor installation — but I boycotted my show out of protest. Beyond this setback, the work continued.

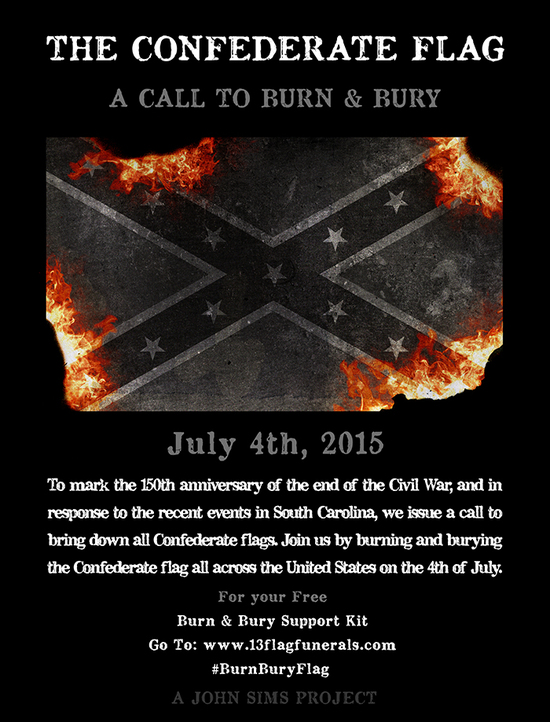

For the 150th anniversary of the end of Civil War and the conclusion of Recoloration Proclamation, a 15-year multi-media project, I organized “The Confederate Flag: 13 Flag Funerals.” This was a funeral/burial group performance in all of the 13 states represented by the 13 stars in the Confederate flag on Memorial Day, May 25, 2015. This lead to the creation of the video poem, “The Confederate Flag: 13 Eulogies” featuring poetic voices from the 13 participating states. These events were intended to finish what I started in Gettysburg and to create a space of ceremonial reflection for the complex desire for the death and burial and perhaps the burning of the Confederate flag as a symbol of terror, treason, supremacy and bearer of the messages that history is rewritable and that Black Lives Don’t Matter.

Then, weeks later, South Carolina happened.

This incident is sadly, not unimaginable, spurred as it was by American racism. The time is now for the Confederate flag to come down in South Carolina, and other states and places where it flies inappropriately. The time is now for federal law prohibiting the use of the Confederate flag in state flags or on governmental property. While taking the flag down is very important, it cannot be a mere consolation prize, for the time is now to address foundational issues with serious strategies that plagues social justice and respect for all Americans.

If we cannot resolve the issue of the Confederate flag, something we can see and touch, how can we as a nation process the complex things we cannot see? If there are cemeteries for Confederates soldiers, then where are the national memorials to the victims and descendants of African slaves who built the economic legacy that this country sits on? What does that say about our country? Or what can we make of the fact that in WWII, Nazi soldier prisoners were often treated better than African-American soldiers by white American soldiers? The Confederate flags flying, the Fergusons, the Eric Gardners and the cases like Baltimore are powerful examples that show there is a consistent lack of respect for black people. And where there is no respect, there is no justice, and then no peace.

So, in the spirit of creative resistance, I am extending the “13 Flag Funerals” project to a countrywide call for the collective burning and burying of the Confederate flag on July 4, 2015. I am asking all Americans to join together on Independence Day to demonstrate that this symbol of slavery, segregation, subjugation and a lost war will not divide us further and that the American Civil War II must come to an end.

John Sims, a native of Detroit is a multi-media political math artist who creates projects spanning the areas of mathematics, art, text, performance, and political-media activism. He is currently completing, Recoloration Proclamation, 15 year multi-media project featuring: an exhibition of recolored and hanging Confederate flags, a multi-state flag funerals, a play, a documentary film and a CD with 13 black music versions of the song Dixie. He lives and works Sarasota, Fl.

— This feed and its contents are the property of The Huffington Post, and use is subject to our terms. It may be used for personal consumption, but may not be distributed on a website.

![]()

Originally from:

Why I Burned and Buried The Confederate Flag — And America Should, Too