On April 10, 2012, Emily Bartlett received a few text messages from a guy who had left her Grinnell College dorm room about 10 minutes earlier. “If you ever tell anyone God help you,” one read. Bartlett did tell someone: That night she told a confidential advocate on the Iowa campus that the male student had sexually assaulted her. A few days later she went to campus security and filed an official report, but she was unsure whether she wanted to see her alleged attacker punished. She said college administrators suggested she request a mediation session with him, a practice the U.S. Department of Education had explicitly prohibited one year earlier in a letter to all colleges. The …

On April 10, 2012, Emily Bartlett received a few text messages from a guy who had left her Grinnell College dorm room about 10 minutes earlier. “If you ever tell anyone God help you,” one read.

Bartlett did tell someone: That night she told a confidential advocate on the Iowa campus that the male student had sexually assaulted her. A few days later she went to campus security and filed an official report, but she was unsure whether she wanted to see her alleged attacker punished. She said college administrators suggested she request a mediation session with him, a practice the U.S. Department of Education had explicitly prohibited one year earlier in a letter to all colleges.

The male student “took responsibility for what he did and regretted it” during the mediation, according to a school document shared with The Huffington Post. But the mediation proved to be a failure, Bartlett said, because it retraumatized her and didn’t bring a resolution to their case. She moved forward with a hearing process.

Despite what Bartlett considered a confession made during the mediation, text message evidence and photos of deep bruising on her body, the college hearing found the accused not responsible for sexual misconduct. He was instead deemed responsible for “disorderly conduct” and “psychological harm” and punished with a year of probation. Campus officials issued the two students a no-contact order. The accused would still be allowed to play baseball and take the same courses as her.

“The no-contact order was a joke,” Bartlett said. “I had a class with him through all of this.”

On paper, Grinnell was doing everything right: It received praise for putting an affirmative consent standard in place in 2012, and its annual stats for sex offenses were among the highest per capita for colleges — suggesting students there were comfortable coming forward to report their assaults. The school even includes gender-neutral pronouns in its student handbook. There are no rowdy frats or big-time Division I sports stars to blame for rape culture, as has happened elsewhere.

But in some cases, Grinnell forced students to attend class with men the school acknowledged to have sexually assaulted them. The college made offenders write short apology letters to victims as their punishment. When some women struggled in classes due to stress related to their assaults, they say, the college pushed them off campus. And when students confronted Grinnell over its failings, student magazine editors lost their jobs and administrators told activists they were being intimidating.

One student, India Vannoy, was placed on academic suspension from the college while her offender was allowed to return to campus. Another woman, a senior who asked to be identified by only her first name, Anna, saw her attacker punished with “conduct probation.” He was also ordered to write an apology letter, but allowed to stay in her classes. He later landed an on-campus job — as head of student security.

While these three cases might not represent the way Grinnell has handled the majority of reported sexual assaults, their consequences have driven two victims away from their dream school and caused daily anxiety for the third, who stayed on campus. The women filed a federal complaint against Grinnell in February due to their concerns the college’s handling of their cases violated Title IX, the gender equity law requiring colleges to address to sexual misconduct on their campus.

Grinnell, with its relatively progressive policies surrounding consent, a student body that’s buying into rape-prevention efforts and an administration actively working to address sexual violence, may be a bellwether for how difficult it will prove for any college to fully address the needs of assault victims. If a prestigious, close-knit college like Grinnell cannot avoid letting down students who report rape, it raises the question of whether any school truly can.

Grinnell said federal privacy law limited how much they could comment on sexual assault cases. However, in anticipation of this article’s publication, the school announced Monday it had requested that the Education Department launch a federal investigation of how it responded to reports of sexual violence.

“Grinnell has a longstanding commitment to creating and fostering an environment free from discrimination and harassment,” Grinnell President Raynard Kington told The Huffington Post. “Despite its small size, Grinnell has embraced its Title IX obligations and in recent years taken significant and expansive steps to assure that our policies, procedures, and practices are legally compliant, trauma-informed, and consistent with promising practices across the country.”

Frustrations over how the college handles sexual assault have enveloped the tiny Iowa campus, creating a face-off between the administration and an activist group of survivors and allies called Dissenting Voices. A progressive student body that views the “only yes means yes” consent standard as a settled discussion — and is proud of its school for having it — is caught in the middle.

“People want to see change happen now and it’s frustrating to know this is a system that goes so deep it’s going to take time,” said Joyce Bartlett, a senior who works as a peer advocate, meaning she’s trained to provide help to victims of sexual violence on campus.

One of the residence hall buildings at Grinnell College that are located in three areas of the campus. Students who reported being sexually assaulted say they struggled with seeing the accused students in the lounges of their buildings.

The liberal arts college dominates the isolated town of Grinnell, Iowa. Fewer than 10,000 people live here, and 1,600 of those are undergraduates at the private school. The student nightlife largely takes place on campus, and it’s roughly an hourlong drive on the highway to the nearest metropolitan city.

“The campus is so tiny, everyone’s lives are all wrapped up in each other,” said Lisa Stern, a junior who works with victims through a hotline run by Grinnell’s Domestic Violence Alternatives Student Assault Center. “It’s really challenging to navigate how to be in different social situations around people’s assaulters.”

The way no-contact orders are enforced on such a small campus is key to how some students say Grinnell failed them, but also shows the challenges for administrators in a tight-knit community.

When a professor told the administration Anna’s offender was sitting next to her in class, for example, the college said there was nothing they would do.

“The burden is placed equally on both of us to not communicate, so if I would say, ‘Get the fuck away from me, don’t sit here,’ like I wanted to, I would be in just as much trouble,” Anna said.

Andrea Conner, the current dean of students, points to several features that limit school administrators’ ability to enforce no-contact orders: “We have one dining hall, the campus is roughly a four-block radius, there are not multiple sections of every course.”

“We work with our students to understand the challenges of navigating a no-contact order in the context of a small geographical area with shared common facilities,” Kington added in a statement. “We also take strong action when the terms of a no-contact order are violated. We recognize the tension inherent in meeting the needs of a complainant and a respondent when both co-exist on the campus and — where possible, based on the facts and circumstances — separate the parties’ housing and class schedules.”

But even experts who acknowledge those hurdles criticized Grinnell’s approach.

“I have trouble understanding what an institution could call a no-contact order that allows a respondent to regularly come in close proximity and not violate the no-contact order,” said John Wesley Lowery, chair of the student affairs of higher education department at Indiana University of Pennsylvania.

“The Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights has never said that expulsion or suspension is required to remedy a hostile environment. But they have said sufficient steps must be taken to remedy that hostile environment,” said longtime campus safety advocate S. Daniel Carter of the VTV Family Outreach Foundation, a nonprofit born out of the Virginia Tech massacre. “No-contact orders can be part of that, but they must be effective at separating the victim and the assailant.”

Seeing her alleged attacker around Grinnell’s campus became too much for Bartlett, who transferred to the University of Missouri in 2013. As recently as December 2014, Grinnell sent Bartlett a letter asking if she would consider returning to the college, and asked her why she “chose to leave.”

“I loved Grinnell, or I loved what I thought Grinnell was,” Bartlett said. “But after all that there was just no way.”

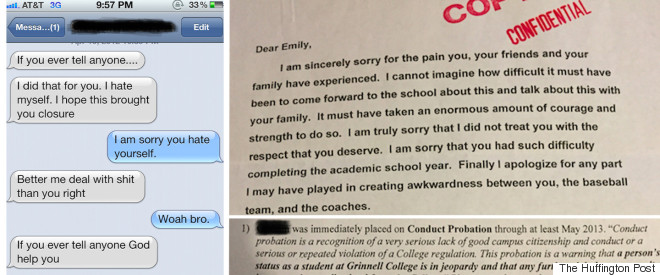

Clockwise: Text messages Emily Bartlett said a male student sent her just after he sexually assaulted her; An apology letter from the student after a hearing into the alleged assault; A portion of the letter describing the punishment the student received for disorderly conduct and “psychological harm.”

India Vannoy left the campus after reporting a sexual assault too, but she didn’t leave by choice.

Vannoy said a classmate in her scholarship program sexually assaulted her in April 2012 during a prospective students’ weekend before she ever started classes.

“The day I was raped I was at the [college] president’s house — literally five hours before I got raped I was with the president,” Vannoy said.

Vannoy filed school conduct charges against the male student in September 2012, as did another woman who said she was assaulted by the same man.

During a January 2013 hearing, Grinnell found him responsible for psychological trauma in Vannoy’s case; psychological trauma and sexual misconduct in the case of the other female student; and selling or distributing illegal drugs, according to college documents. He was suspended for three semesters and eligible to petition to return to school in spring 2014.

After the hearing, Vannoy was clinically diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder, and took the rest of the spring 2013 semester off to recover. She returned in the fall, but landed on academic probation due to her declining grades, and had to appear before the Committee on Academic Standing.

Grinnell Title IX Coordinator Angela Voos said the college typically would do “anything we can think of to help people navigate this difficult thing,” which may include reaching out to professors on a victim’s behalf.

But Vannoy said she did not receive the assistance she needed. An administrator told her she was “mentally unstable” and suggested she “should really take some time to get yourself together and get over this,” Vannoy claimed. She was placed on academic suspension, and her petitions to return have so far been denied by Grinnell — meaning the attacker is allowed back on campus, but Vannoy is not.

“That’s where I started my education; that’s where I’d like to finish,” Vannoy said. “I worked very, very hard to get into a school as rigorous as Grinnell.”

Grinnell College has a small campus, located in a rural part of Iowa near Interstate 80. It’s an hourlong drive to Des Moines, the state’s capital, or to Iowa City, where the University of Iowa is located.

Grinnell’s hearing panel for rape cases is like that of many colleges: It includes a student, a professor and a staff member who received special training about sexual violence and Title IX. Yet like many colleges, it’s moving toward a single-investigator model. The school is hiring former Iowa Supreme Court Chief Justice Marsha Ternus to handle future assault cases.

Most of the student victims Voos speaks with don’t want to engage in an adjudication process, according to numbers that she tracks. Anna’s frustrating experience may provide clues as to why.

When a hearing panel took up her case in May 2012, they asked her what kind of bra she was wearing the night of the incident, Anna said, and allowed the accused student to directly question her, a practice “strongly discouraged” by the Department of Education. Anna said the accused asked her, “Why are you doing this to me? Why couldn’t we have just talked about this?”

When Anna got to speak, she described explicitly saying “no” and crying during the assault.

“He said he was essentially teaching me about sex and he had a better idea about what I wanted than I did,” Anna said.

Anna’s offender was found responsible for “disorderly and disruptive behavior,” “psychological damage” and “sexual misconduct,” according to documents obtained by HuffPost. The school didn’t find him guilty of rape — a criminal term — but did find him accountable for “nonconsensual penetrative intercourse.” Conduct probation would serve as his punishment.

He also had to write a letter of apology, which the college delivered to Anna in July 2012. In the letter, which is five sentences long, he admits his “actions on the night of February 9th did not meet the definition of effective consent,” and says he hopes he will “never commit such a heinous offense ever again.”

When a student is found responsible in sexual misconduct cases, the college’s first consideration as a sanction is always dismissal, said Conner, the dean. Grinnell then works backward from there depending on “mitigating or aggravating factors,” she added.

“We do our best for our sense of ethics and appropriateness,” Conner said.

Anna stayed on campus, but in September 2014 gave up on trying to get the college to hold her offender accountable for the alleged violations of the no-contact order, or for harassment she reported by his friends. Adding salt to her wounds, he was hired by the college this academic year for a student security job that gave him oversight of campus events, essentially to make sure students are being safe at parties. The college recently said any student still on probation would not be eligible for this position in the future, and he resigned his position as Anna raised concern on campus about his role.

The accused student in Anna’s case told HuffPost he realizes he did violate the school’s consent policy at the time, but chalks it up to “mixed signals” and doesn’t consider it rape. At the time, Grinnell used an “effective consent” policy that stipulated consent must be “informed, freely and actively given,” and could not come from the use of “intimidation, or coercion.” The school switched to “affirmative consent” in fall 2012, which states that consent must be given for “each act of sexual activity,” and can be withdrawn at any time.

The accused student said he’s “pissed” with how Grinnell handled the case as well: The no-contact order meant he could stay in school but couldn’t take certain classes, and to avoid violating his probation he had to take routes far out of his way at a time when he was on crutches due to an athletic injury.

“If the school really thought that I was guilty of this, I shouldn’t be here; if my case was as serious as Anna made it out to be, I shouldn’t be here right now,” he said, adding, “I’m grateful it hasn’t changed my views on how I saw rape — I’m not questioning every single woman that said that it happens to them.”

Vannoy’s alleged assailant maintains it was consensual intercourse, and his attorney sent a statement suggesting colleges are elevating regretted sex to sexual misconduct. Bartlett’s alleged assailant could not be reached for comment. The accused men are not being named because they have not been charged with a crime in connection with these cases.

The anger may never have become so public had an editor for a student magazine not been fired for running an op-ed by Anna criticizing how the college punishes sexual assault.

Frustrated with portrayals in various news outlets of Grinnell as a shining example of a college handling sexual assault responsibly, Anna wrote an op-ed in October 2014 for the Grinnell Underground Magazine, or GUM. In it, she criticized how the school punished her attacker, and Grinnell’s administration was outraged she used the phrase, “The student was found responsible for raping me.”

After meeting with Grinnell administrators, the head of student media fired Linnea Hurst, the editor who published the op-ed, for flirting with “libel and slander” by allowing a phrase she allegedly knew to be “factually inaccurate” be published. The student media leaders feared a lawsuit, though they truly had no idea who — if anyone — was going to file one. Another sin the student media leaders said Hurst committed: She didn’t give as much Facebook promotion to the administration’s response op-ed as she had to Anna’s piece.

Hurst said she couldn’t understand why the school was so upset by the phrase, since, after all, “You can’t say she was ‘sexually misconducted.'”

“I thought Grinnell was a pretty good place for women,” Hurst said. “I thought it was fine, then everything was exposed to me. That got me very aware very quickly it was a huge fight.”

Students formed the group Dissenting Voices and began demonstrating on campus after the flap at the GUM. When administrators would speak about sexual assault, the protesters would show up with red tape over their mouths to symbolize what they felt as their freedom to use the word “rape” being silenced. After one forum, administrators called the protesters “intimidating,” student activists said.

Grinnell officials said they have tried to explain to student activists the school can’t use “rape” because it’s a legal term. Voos also suggested it’s “heteronormative.”

“Schools have no legal authority to determine a crime has taken place,” explained higher education consultant Brett Sokolow, president and CEO of the National Center for Higher Education Risk Management. When a school requests a student avoid using the term, “it’s not meant as a gag order, it’s just that most victims don’t understand how litigious these things can be.”

Grinnell students organized a protest in fall 2014 after a student was reprimanded for an article criticizing the school’s response to rape.

Grinnell is not under federal investigation yet, but has acted similarly to colleges that are. It hired well-known campus sexual assault consultants Gina Smith and Leslie Gomez to review its policies. It has an ongoing task force on the issue. Voos said she informally provided guidance on the sexual violence policies at Occidental College, another small liberal arts school accused of handing out lax punishments for rape.

“We’re a small community. I think we’re doing pretty well so far; not everybody’s happy and we know that,” said Jim Reische, Grinnell’s vice president for communication.

The college declined to speak on specific cases, citing federal privacy law. But Kington, the school’s president, did note Grinnell no longer uses mediation in sexual assault cases, and it stopped allowing accused students to directly question complainants in 2013. Kington, who took charge of Grinnell in 2010, said the school “proactively initiated a number of changes after commissioning a thorough external review” two years into his tenure.

“Our changes took into account the actions OCR was requiring of other institutions,” Kington said. “Our external review also included seeking feedback from complainants and respondents about their experiences with the College’s processes. That feedback was instrumental in guiding our actions.”

Some students, like Grinnell soccer player Michael Hurley, feel like the college is “really ahead of the curve” with its policies. But as Dan Davis, a Grinnell senior, pointed out, “We’re doing better than 95 percent of colleges, but 100 percent of colleges are doing terrible.”

Many students who spoke with HuffPost felt the affirmative consent standard was widely accepted among students. But they acknowledged there was tension on campus between activists and the administration over its handling of cases.

Opeyemi Awe, president of the student government, said she doesn’t feel like students are constrained by administration policies at all. She and others proudly noted the affirmative consent policy came at the request of students three years ago.

“I would say we have primary control — we very rarely have members of the administration stepping in and saying, ‘You can’t do this, and you can’t do this.’ So Grinnell is different in that way,” Awe said. “We are so involved in how we create the culture that we also have a responsibility to change that culture.”

Student leaders are exploring changes they can push for beyond the investigation process and consent policy. The Grinnell Student Government Association is currently leading a working group on the conduct process, soliciting input from students for further reform proposals.

It’s hard to ignore Dissenting Voices’ opinion at this point, which Awe described as “one extreme.” She said she feels like “other students are put off by their tactics.”

Activists with the group said in response that they spent three years holding quiet meetings with college administrators, to no avail. They also pointed out that some of their actions have come in the form of documentary screenings and a bake sale to raise money for victim services.

“Yes, sometimes action looks scary and confrontational … when such action is motivated by deep sympathy and compassion,” members of the group said in a statement. They said they think all administrators and students want the campus to be as safe as can be, and that their protest “should be a cause for concern and an opportunity for engagement and empathy from the rest of the community.”

College officials acknowledge they’ll have to continually adapt to federal guidance and concerns brought forward by community members. Yet they are also clearly concerned by how complicated these cases are, and how difficult it can be to assist students going through traumatic experiences. Additionally, due to confidentiality issues, it’s not always possible to discuss every critique.

“You are never going to hear about the cases that students are satisfied with the outcome,” Voos notes. “That’s really OK, but it’s unfortunate, because it’s a very lost conversation.”

Need help? In the U.S., visit the National Sexual Assault Online Hotline operated by RAINN. For more resources, visit the National Sexual Violence Resource Center’s website.

More:

Why Even Small, Progressive Grinnell College Has Trouble Dealing With Sexual Assault On Campus