On Tuesday afternoon, Dane County District Attorney Ismael Ozanne stood before a crowded press conference and announced that Madison, Wisconsin, police Officer Matt Kenny, who is white, would not face charges in the March 6 fatal shooting of 19-year-old Tony Robinson Jr., an unarmed biracial man. With streams of sweat pouring down his brow, Ozanne — the first person of color to hold this office in the state of Wisconsin — began to paint the events leading up to Robinson’s death. He launched into a description of a series of 911 calls that were placed before Kenny arrived on the scene. Robinson was “tweaking,” said one caller. He had taken mushrooms — and other drugs — and was…

On Tuesday afternoon, Dane County District Attorney Ismael Ozanne stood before a crowded press conference and announced that Madison, Wisconsin, police Officer Matt Kenny, who is white, would not face charges in the March 6 fatal shooting of 19-year-old Tony Robinson Jr., an unarmed biracial man.

With streams of sweat pouring down his brow, Ozanne — the first person of color to hold this office in the state of Wisconsin — began to paint the events leading up to Robinson’s death.

He launched into a description of a series of 911 calls that were placed before Kenny arrived on the scene. Robinson was “tweaking,” said one caller. He had taken mushrooms — and other drugs — and was “going crazy,” said another. He was acting aggressively and unpredictably, said the third and final caller. Ozanne repeatedly stressed these details. They were, after all, crucial to the decision he was preparing to announce: that Robinson was essentially to blame for his own death.

The person Kenny says he confronted on that March evening was a man possessed: violent, crazed, under the influence of unknown substances and intent on attacking Kenny. Kenny claimed — and Ozanne ultimately agreed — that these factors sufficiently explained why he felt he had to fire seven shots into the body of an advancing Robinson.

“I conclude that this tragic and unfortunate death was a result of a lawful use of deadly police force and that no charges should be brought against Officer Kenny in the death of Tony Robinson Jr.,” Ozanne said.

In cases in which charges are not brought against an officer in a police killing, authorities have successfully shifted some blame onto the victim in order to support the assertion that an officer acted legally in using lethal force. The implication is that it isn’t the officers’ job to stop themselves from killing people — rather, it is the people’s job to not get themselves killed by the officers.

For example, in court filings in the case of Tamir Rice, a 12-year-old killed by officers last year while playing with a toy gun in a park, the city of Cleveland said Rice was responsible for his own death and claimed the shooting was “directly and proximately caused by the failure of [Rice] to exercise due care to avoid injury.” The city later amended some language in the filing, but maintained its initial defense. A decision on whether to indict the involved officers is still forthcoming.

When these sorts of arguments are used to explain why an officer won’t be charged in a shooting, the public is left with the sense that the officer was right and the victim was wrong. Much of that is a function of the investigative process, which doesn’t allow for a lot of gray area: Under Graham v. Connor, a crucial 1989 Supreme Court that relates to use of force by officers, prosecutors must judge an officer’s actions based on the perspective of “a reasonable officer” on the scene. They don’t have the benefit of 20/20 hindsight — instead, they must evaluate how the officer responded to the situation they were presented with, not what they could have done differently or whether they should have been in that situation at all.

While law enforcement advocates say this a necessary protection for police officers who must respond to difficult and dangerous situations, it also shapes the broader debate over police tactics and misconduct by eliminating much of the middle ground. The ACLU of Wisconsin made this point in a statement following Ozanne’s announcement.

“The ACLU of Wisconsin regrets District Attorney Ozanne’s decision because it leaves a cloud of uncertainty over the circumstances of and the responsibility for Tony Robinson’s death,” the organization’s executive director, Chris Ahmuty, said. “If Officer Kenny did not violate the law, then is anyone legally responsible for Mr. Robinson’s death? Does the criminal law protect individuals like Mr. Robinson from deadly force exercised by police officers? Are police officers above the law?”

To make matters more frustrating, the decision not to indict is typically accompanied by a sense of incontrovertible finality: The justice system — the only way to hold officers criminally liable for their actions — has considered the case and closed it for good. Furthermore, the public has been given little reason to believe that a police department would second-guess the use of deadly force by an uncharged officer and voluntarily pursue disciplinary action or policy changes in light of such a controversy. The question of an officer shouldering some of the blame may arise again during subsequent civil suits, though police departments usually look to settle, which saves costly legal fees and ensures the actions of their officers aren’t scrutinized further.

The cases below have all failed to produce criminal charges for the officers involved. But they leave us with a variety of questions that can’t be answered simply by having a prosecutor decide that it was the victim — and definitely not the officer — who was somehow at fault. Even if we accept the finding that the victims were killed legally, it doesn’t answer a more pressing question: Did these people really have to die?

What, if anything, could an officer have done differently to keep that from happening? Until we’re willing to confront the fact that officers hold some responsibility in many of these cases — even if it’s not in the criminal sense — we’ll continue to resort to finger-pointing instead of having a productive debate about what steps police might be able to take to keep these tragedies from happening so frequently.

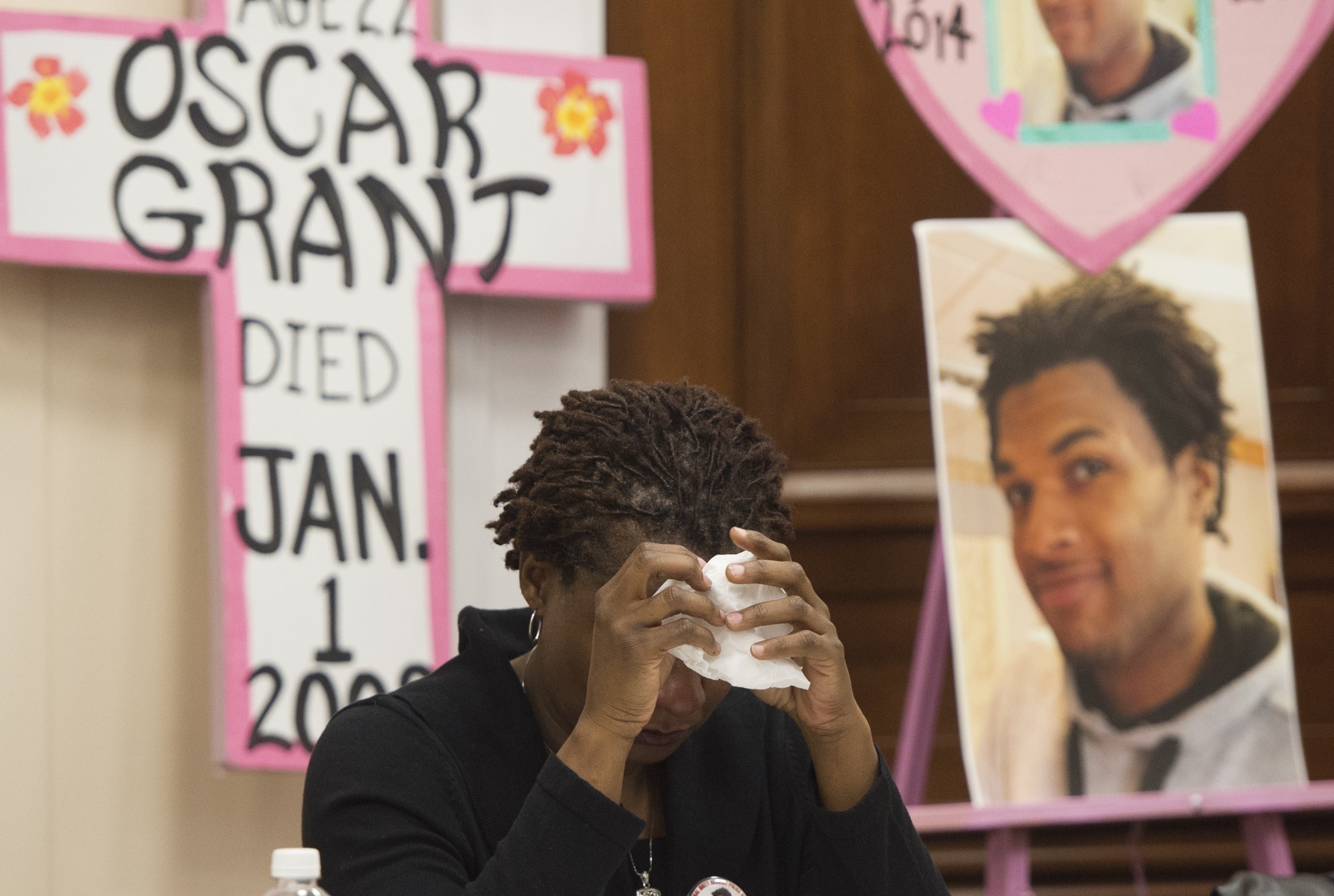

Tony Robinson, Jr.

Who’s been blamed?: Robinson, for being high on drugs and aggressive toward the responding officer.

What this misses: Robinson was clearly vulnerable and a potential hazard to himself and others at the time of this confrontation. But perhaps that should be a reason to approach a situation with more, not less, caution — both for the safety of the officer and the suspect.

It’s been pointed out that police in Madison and around the nation could benefit from re-evaluating how officers are trained to engage with potentially violent people, even if they’re unarmed — retreating, taking cover and talking down suspects could yield better results than going head-on into a situation that will likely require physical force. Additional training and tools that would encourage officers to use Tasers or other weapons less lethal than their firearms could also help police more peacefully address potentially dangerous suspects.

Rekia Boyd

Who’s been blamed?: Boyd, for being in the vicinity of her boyfriend, Antonio Cross, who had a cell phone that the officer said he thought was a gun.

What this misses: Though Officer Dante Servin was initially indicted in the death of Rekia Boyd, he was eventually found not guilty on all charges. Servin expressed little remorse for Boyd’s death and maintained that, though her boyfriend was unarmed, the officer shot out of fear of becoming “a police death statistic.”

“Any reasonable person, any police officer especially, would’ve reacted in the exact same manner that I reacted,” he said of his decision to fire an unregistered firearm over his shoulder toward a group of people while in his car. “And I’m glad to be alive. I saved my life that night. I’m glad that I’m not a police death statistic. Antonio Cross is a would-be cop killer, and that’s all I have to say.”

These public comments after being cleared of the charges highlight how the legal process offers complete vindication for officers and actually discourages any deeper reflection about how their actions may have also contributed to a controversial incident. Did Servin, who was off duty at the time, really need to take matters into his own hands if he’d already called 911 to file a noise complaint? Why didn’t Servin identify himself as a police officer before the incident escalated and he fired off a round of shots? Also, what do Servin’s actions tell us about implicit stereotyping and the assumption that some people are perceived to be more dangerous than others?

John Crawford

Who’s been blamed?: Crawford, for holding a BB gun in a Walmart in Ohio — an open-carry state.

What this misses: Crawford was dead within one second of encountering law enforcement officers, according to a wrongful death lawsuit filed by his family. “Mr. Crawford was shot before he even had time to react to the officer’s presence, much less to comply with any verbal commands,” the suit alleges.

Officers involved in Crawford’s death said they shot the father of two after giving him multiple warnings to drop what he was holding. But video surveillance footage suggests Crawford was shot almost immediately, and that the officers made no attempt at de-escalation. That such a swift and extreme response was based on a 911 call reporting there was a man in Walmart holding a gun — information that proved to be unreliable — is concerning, and raises questions about the role perceived black criminality may have played.

If other citizens — and therefore, responding officers — are more likely to see black people as a greater threat, they may be quicker to use force, even when it isn’t needed. Though such assumptions are usually based on implicit stereotyping, any conversation on how police can be better trained to confront and deconstruct these biases disappears when we’re told that the officers who actually shot and killed Crawford don’t hold any responsibility for his death.

It’s worth having a more substantive dialogue about how police interact with with “armed” suspects — and the conversation should have been initiated after LeeCee Johnson, the mother of Crawford’s children, said Crawford tried to tell officers the BB gun wasn’t a real weapon before he was shot. The case also shows that witness accounts can be unreliable, suggesting that they should inform, but not determine, the actions of an officer responding to a possibly tense situation.

Jason Harrison

Who’s been blamed?: Harrison, for holding a screwdriver.

What this misses: Around 50 percent of people shot and killed by police each year suffer from some form of mental illness, according to a 2013 report from the Treatment Advocacy Center and the National Sheriffs’ Association.

Harrison’s mother was well-known to police, as she’d frequently call them to assist with her son. On June 14, 2014, she phoned 911 and specifically requested officers who were trained to handle the mentally ill so that her son could be taken to the hospital.

Whether Officers John Rogers and Andrew Hutchins were equipped for that job is questionable. After arriving on the scene, Harrison’s mother informed officers that her son suffered from schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Harrison appeared in the doorway behind his mother, and within five seconds of the initial command to drop the screwdriver he was fiddling with, Harrison was shot.

The speed with which officers used lethal force on Harrison is jarring, especially as he didn’t seem to be posing an immediate threat by holding a screwdriver. The Atlantic pointed out that instead of talking Harrison down, officers stood their ground, pulled their weapons and agitated the situation by yelling at a mentally unstable man holding a potential weapon.

Cops are often trained to view hesitation as a flaw that can get them killed. Thus, The Atlantic reports, they are “trained to shoot before a threat is fully realized, to not wait until the last minute because the last minute may be too late.” But surely that mentality is not meant to be applied equally to every potential threat. Why not use a nonlethal weapon to subdue Harrison instead? Perhaps the bigger question is: How can police training be retooled so that officers view lethal force as a last resort used in the best interest of the community, instead of a means to protect themselves at the cost of the people within it?

Dillon Taylor

Who’s been blamed?: Taylor, for matching the description of another suspect and reaching for his waistband while intoxicated.

What this misses: Not following an officer’s command fast enough — or verbally pushing back against it — is frequently used to justify a police killing. A suspect’s resistance or attitude toward an officer seemingly trumps any consideration of how the situation could have been handled better by the officer.

“Nothing that Mr. Taylor did assisted in de-escalating the situation,” Salt Lake County DA Sim Gill told The Salt Lake Tribune. “If anything, it escalated things.”

But nothing Bron Cruz, the officer who shot and killed Taylor, appears to have de-escalated the situation either. A video of the incident shows that Cruz pulled his weapon almost immediately after approaching Taylor and began screaming commands — heightening the tenseness of the situation before he had established whether Taylor was the suspect he was looking for.

Gill also noted that some of Taylor’s Facebook posts suggested he was suicidal, downplaying that an innocent man had died.

Robert Cameron Redus

Who’s been blamed?: Redus, for being drunk and resisting arrest.

What this misses: Could University of the Incarnate Word Officer Chris Carter have approached this situation in a way that might have kept the confrontation from getting so hostile? An audio recording of the last 11 minutes of Redus’ life indeed shows he was uncooperative after being pulled over for erratic driving. But it is also clear that there was ample opportunity for Carter to try to calm the situation and allay concerns Redus voiced about how he was being treated, including fears that the officer was touching him inappropriately.

Carter is, of course, not obligated to be polite to Redus or any other suspect. Nor should he be required to by law. But perhaps there is an overeagerness to resort to force, in some cases catalyzed by the behavior of the officer. Could a change in tone or softer approach have kept the encounter from becoming dangerously volatile? In any case, if Carter had opted to initially address Redus differently and still ended up shooting him five times, what would the officer have lost?

There are also questions about why Carter wasn’t armed with a less-lethal option, such as pepper spray or a stun gun. Should a case like this influence departmental policy about what weapons their officers should be outfitted with and when they should use them?

Each of these cases provides a number of teachable moments that could equip officers to make better decisions and be proactive about preventing the tragic consequences of deadly force — even if such force is deemed legal. As it stands now, however, in order to prove their innocence, officers must maintain that there was nothing they could have done differently. When the justice system agrees — which it overwhelmingly does — we’re left to believe victims have invited their own deaths and that cops have had no choice but to oblige them. In that situation, no one wins.

— This feed and its contents are the property of The Huffington Post, and use is subject to our terms. It may be used for personal consumption, but may not be distributed on a website.

See the original post: