“Grab that one! Hurry. Hurry!” I was 8 years old running through an orchard with my friends. It was fall, the sun was shining, the apples in the orchard glowed like neon red orbs, the branches strained under their weight seeming to droop down toward us, tempting us further, tempting us sufficiently that we were willing to make a run through the orchard during harvest season, chasing forbidden fruit. “Duck! Get down.” One of the boys warned. “What?” “I think I saw something.” Tommy was one of the older boys — 10 years old. And suddenly he was off like a shot, running hard. “Jigaboo on foot!” He yelled. We all …

“Grab that one! Hurry. Hurry!”

I was 8 years old running through an orchard with my friends. It was fall, the sun was shining, the apples in the orchard glowed like neon red orbs, the branches strained under their weight seeming to droop down toward us, tempting us further, tempting us sufficiently that we were willing to make a run through the orchard during harvest season, chasing forbidden fruit.

“Duck! Get down.” One of the boys warned.

“What?”

“I think I saw something.” Tommy was one of the older boys — 10 years old. And suddenly he was off like a shot, running hard.

“Jigaboo on foot!” He yelled. We all took off.

This was the call that the kids made if one of the black orchard workers was nearby — we scattered, running as far and as fast as we could, shirts formed into bibs, apples bouncing up and down with each stride, all of us smiling, laughing, scurrying to safer quarters. That word was only shocking later. It was not said with animosity — it was just a fact, a warning, an alarm — but of what I only understood later.

This was farce — no one ever chased us, no real threat existed, the orchard workers could care less about a dozen apples missing among thousands. But they no doubt cared about the word. Jigaboo. This was my introduction to race in America — which at 8 years old was a fish’s introduction to the water. I remember thinking — is that ok to say? But none of us talked about it, no one questioned it. It just was.

As a middle class white kid, for many years, this is what I thought racism was, a dialogue about figurative black and white — you said something racist or you didn’t, you were a racist or you weren’t. And of course that is partially true — but the far deeper, long-term and devastating acts of racism have little to do with what you say, what names you call someone. They are institutional — the deliberate construction of a distorted playing field that ensures that if you are black you cannot get a mortgage in a white neighborhood, you will get arrested and convicted for drug use at many times the rate of white drug users, you are more likely to get killed by police while unarmed, the grim list goes on.

Through all the racially motivated tragedies of the last several decades and the ones that are coming to the surface, finally, in the last year, including Ferguson and the movement that followed and the terrorist murders in Charleston, NC, we as a nation are on the verge of starting to have a deeper conversation about race. And now, after so many years of pretending issues of race were not right in front of us, race is once again, like so many times in US history, seeming to manifest itself everywhere.

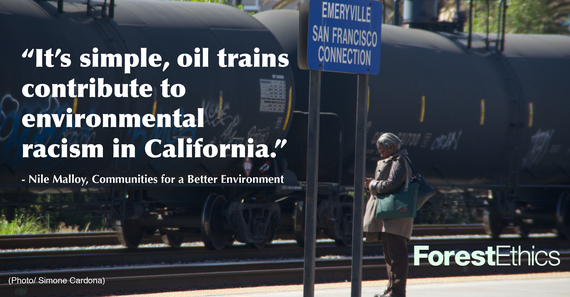

Institutional racism in the United States has profound impacts on who lives where, near what, and with how much exposure to risk. This week my organization, ForestEthics, partnered with our ally, Communities for a Better Environment, to release a report in which we analyzed who was at the greatest risk from oil trains in California. The risk in this case is both explosions (there have been five major derailment explosions in 2015 alone,) as well as the longer-term health impacts of diesel fumes and off gassing from these oil trains (they lose 1-3% of volume during transit via toxic gaseous emission).

The results are stunning — dark skinned and poorer communities received not just disproportionate risk, in some cities 100% of the risk from oil trains was borne by lower income people of color (Fremont and San Bernardino), with Oakland, San Jose and Stockton putting over 90% of this risk on these communities.

Transporting millions of gallons of oil on mile-long trains through our cities, towns, alongside our water supplies, and through our forests is a kind of insanity. Doing all of this while saddling dark skinned and poor communities with most, or in some cases, all of the risk, is morally repugnant. It is time to ban oil trains. If they can’t haul this explosive, toxic crude safely, they shouldn’t haul it at all. And those that do — Warren Buffett and his BNSF railroad primarily — should confront the choice they are making and who they have chosen to put at risk.

Our country is almost daily confronted with a ghost from its past, whether it’s the legacy and current practice of police violence, the Confederate flag inspired killings of black parishioners and their Pastor, the racist remarks of a presidential candidate… and we will see what is in the news tomorrow. Now we can add oil trains and who is threatened the most by explosions and pollution to the list.

Little by little, we are getting closer to a deeper conversation about race — and what we can do to correct our ugly history so that the actions of the future are not continuously bound by the racist policies and practices of the past. We are not there yet, but this issue isn’t going away. It will keep reappearing in different forms — we are like the fish that can’t quite see the water it’s swimming in, but little by little we are getting the feeling that there is a pervasive injustice tainting the environment around us. It is our job to make sure the water that some future generation is born into isn’t poison.

PS: I want to thank angel Kyodo williams (@ZenChangeAngel) for her leadership and guidance with this piece.

Originally posted on ForestEthics.org, July 3, 2015.

— This feed and its contents are the property of The Huffington Post, and use is subject to our terms. It may be used for personal consumption, but may not be distributed on a website.

View original –

What Do the Ferguson Movement, the Charleston Killings and Oil Trains Have in Common?