As part of my Fall 2015 PhD Research Colloquium course, I extended the opportunity for my Administration of Justice Doctoral Students to begin writing for the masses. Below you will find the first acceptance of this olive branch by Whitney Threadcraft-Walker. Whitney Threadcraft-Walker is a doctoral student in the Department of the Administration of Justice at Texas Southern University. Her research focuses on the interaction between gender, race and crime, as well as prisoner reentry. A curious affair happened a few weeks ago when assorted media outlets looped footage of 15 year old Dejeeria Becton being slammed to the ground by Officer David Eric Casebolt …

As part of my Fall 2015 PhD Research Colloquium course, I extended the opportunity for my Administration of Justice Doctoral Students to begin writing for the masses. Below you will find the first acceptance of this olive branch by Whitney Threadcraft-Walker.

Whitney Threadcraft-Walker is a doctoral student in the Department of the Administration of Justice at Texas Southern University. Her research focuses on the interaction between gender, race and crime, as well as prisoner reentry.

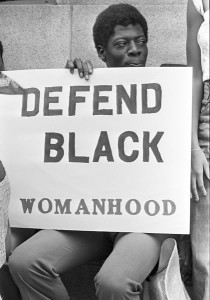

A curious affair happened a few weeks ago when assorted media outlets looped footage of 15 year old Dejeeria Becton being slammed to the ground by Officer David Eric Casebolt in McKinney, Texas. The emergence of yet another controversial recording of an encounter between a police officer and an unarmed citizen hardly gave the nation pause, nor did the subsequent backlash that followed. Instead, more interestingly, the national conversation on police brutality did something it had never done before, centered itself around the gender specific violence experienced by Black women and girls at the hands of law enforcement officers. Despite the efforts of such movements as #SayHerName and #BlackWomensLivesMatter, members of the general public are more likely to know the names of Michael Brown, Freddie Gray, and Walter Scott than Rekia Boyd, Mya Hall, or Kathryn Johnston, who similarly died after encounters with police. While most agree that these conversations are a step in the right direction toward a pathway of increased parity in policing, it can be argued that the notable absence of Black women and girls from this sociopolitical dialogue of victimhood is simply another link in a successive chain of apathy toward those at the very nexus of institutionalized gender and race- based violence.

Historically speaking, violence toward Black women and girls is just as conventional in the U.S. as barbeque on the Fourth of July. Some might even argue that violence against Black women is more common than the Fourth of July as the holiday occurs only once a year. For context, consider the hellish experience of those women and girls forced across the Atlantic to this country for their unpaid labor nearly three centuries ago. Faced with near daily promises of rape and other varied forms of assault, enslaved Black women were powerless to resist the violence of slave masters, or fellow slaves for that matter, as colonial laws did not grant legal recourse to chattel. Black women and girls had no claims to their own bodies as private or autonomous beings as they were repurposed for public consumption to be used and abused at the whim of those not only with authority and power, but by those possessing the means, opportunity or mere inclination. In this regard, the violence endured by Black women and girls became so common place because it was purposive, in a sense that it was meant to subdue and orient Black women and girls into a subjugated place in society. Accordingly, threats of rape and other similar violence in order to dominate, intimidate and threaten persisted from the Post Reconstruction Era well into the Jim Crow South. A time that produced such social change agents as Recy Taylor, Claudette Colvin and Endesha Mae Holland who stalwartly imparted their experiences with sexual violence to better detail an often neglected, and far less publicized, accounting of the seeds of social injustices that germinated the Civil Rights Movement. With the horrors of slavery and the Jim Crow Era serving as the bedrock of sexual violence against Black women, few are familiar with the nameless African slave women who endured medical violence while serving as guinea pigs for Dr. J Marion Sims, often referred to as the father of modern gynecology. Widely regarded by many as an intrepid pioneer, while others question the ethics of operating on a captive population incapable of consenting to treatment; Dr. Sims perfected the technique for treating vesico-vaginal fistulas by performing surgeries on enslaved Black women. Often these surgeries occurred outside in a corner of his yard that he had relegated for his slave subjects, without anesthesia as these women were thought to feel less pain than their white counterparts. Similarly, this same logic has had modern manifestations in contemporary medicine as studies indicate that implicit racial bias influenced both Black and white physicians alike, as they routinely provided inadequate pain management and recommended more invasive procedures to Black women. Plainly stated, this failure to recognize the pain and suffering of Black women by those tasked with the very obligation of healing and care speaks to a larger social context where the inability to register the very humanity of Black women has been normalized.

This apparent apathy for Black women and their suffering is not limited to the annals of history or medicine, in fact it can be easily observed in numerous aspects of social life. Take for instance the reluctance of mainstream media to cover the hundreds of Black women and girls who go missing every year. Just this month the remains of two Black teen girls were found on the same stretch of interstate in New Orleans within weeks of each other, a story that has yet to garner national, or regional, attention. Further, even in stories where Black women comprise the majority of those who have suffered, the conversation still tends to center on males. The shootings that took place at Emmanuel AME church in Charleston on June 17th provides one such example. While no one can lament the remembrance of the victims of this tragedy, the breadth of media attention has focused near exclusively on the Reverend Honorable Clementa C. Pinckney. President Obama has already been confirmed to not only attend his funeral, but deliver the slain public servant’s eulogy. Although, six of the nine victims who died that day were Black women, there has been negligible media coverage describing the lives or achievements of these women. Some might point to Reverend Pinckney’s position as a state senator as the rationale for his increased coverage, however those individuals need only consider the fact that outside of a thoughtful write up on the online community Buzzfeed, little else has been presented to attest to these women’s lives, careers or accomplishments. Few, if any, mainstream media outlets have discussed the fact that Sharonda A. Colemon-Singleton was a noted speech language pathologist at an area high school in Charleston, or that Cynthia Hurd obtained a masters degree in library science and went on to use that degree working for the Charleston County Public Library systems for over 30 years. These women were far more than could be conveyed in a 10 word byline or a 15 second sound bite, as such it is imperative to acknowledge their humanity beyond a footnote on a terrible page of American history.

Undoubtedly, in the wake of the shootings the general public arguably knows more about self-confessed shooter Dylan Roof than any of the women he killed. This story and others like it reinforces both the low level of concern for Black women as victims, while simultaneously discounts their victimization as commonplace. Further still, the failure to register the varied forms of violence visited upon Black women extends beyond the realms of medicine, history, media and the state, into the most sacred of private domains, the home. Consider the stark reality that data compiled using the FBI’s Supplemental Homicide Report found, indicating that Black women are more than twice as likely as white women to be killed by men. Despite the fact that the majority (52 %) of these women were killed by significant others, there has been a veritable lacuna of national initiatives or policies that address this form of violence aimed at Black women.

In sum, the issue is clear: When Black women are victims of violence, the response (given there is one) from the general public is lukewarm at best. Moreover, the impassivity that Black women are met with when they are victims of violence is not a new phenomenon. On the contrary, there is long and complex history of Black women and violence in this country that has occupied the periphery of both public and private conversations of victimhood. The victimization (and apathy toward said victimization) of Black women is so thoroughly ingrained in the collective consciousness of this country that it can indeed be considered mundane, the status quo, or normal. In terms of crime, the type of gut wrenching violence that took the lives of nine innocent citizens in Charleston occurs relatively infrequently. The glossing over of Black women as victims of violent crime, however, is sadly, more common than not.

— This feed and its contents are the property of The Huffington Post, and use is subject to our terms. It may be used for personal consumption, but may not be distributed on a website.

![]()

Link: