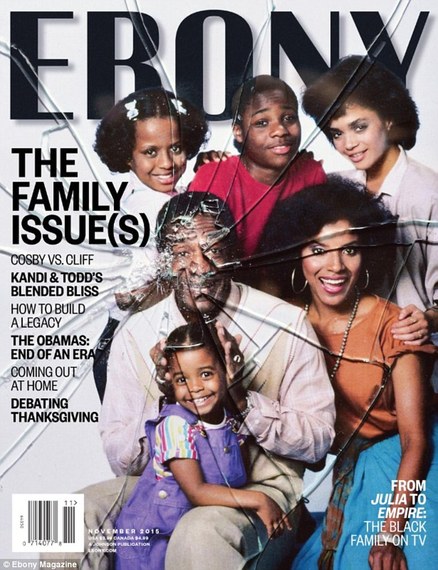

The upcoming piece in Ebony magazine’s November issue, “Can ‘The Cosby Show’ Survive? Should It?” has set black America on fire with a much-needed discussion on the impact of the Cosby show, and the recent allegations of rape against Bill Cosby. The core analysis is a critique of the man Bill Cosby is off camera, and whether it should affect the historical legacy of the show he created. But, if you dig deeper the piece does an impactful analysis of the show itself, and what the creators had to do to present the nuclear black family as successful to America in the early eighties. The show walked the …

The upcoming piece in Ebony magazine’s November issue, “Can ‘The Cosby Show’ Survive? Should It?” has set black America on fire with a much-needed discussion on the impact of the Cosby show, and the recent allegations of rape against Bill Cosby. The core analysis is a critique of the man Bill Cosby is off camera, and whether it should affect the historical legacy of the show he created.

But, if you dig deeper the piece does an impactful analysis of the show itself, and what the creators had to do to present the nuclear black family as successful to America in the early eighties. The show walked the fine line laid out by a country that wanted to be post-racial only twenty years after Jim Crow signs had hung at local restaurants. Creators balanced the expectations of a post civil rights America’s desire to become the visualization of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s dream, and how that fit inside of African-American reality.

For eight seasons on NBC–five of which it was the country’s most-watched program, according to Nielsen ratings–Cosby’s portrayal of Heathcliff Huxtable–a physician, loving husband and doting Black father-reinforced the widely held virtues of the nuclear family, if not also unwittingly illuminating the hazards of respectability politics (the notion that if Black people simply act “good” and “behave,” the world-at-large will treat them as such.) “Ebony Magazine: Can ‘The Cosby Show’ Survive? Should It?”

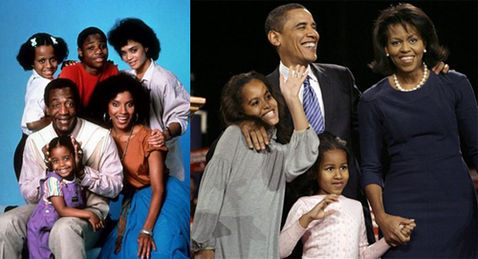

As we look back at the show and its influence, we begin to perform a critique that is long overdue. I will say undoubtedly it is my belief that the show’s legacy is one that reaches all the way to the White House. I agree with Oprah’s statements, “we probably wouldn’t have the president we have in the White House right now had there not been the Bill Cosby show. Because the Bill Cosby show introduced America to a way of seeing black people…”

Yet, despite this positive impact on the exceptional black individuals’ acceptance into white America’s psyche, it may have done the opposite for America’s ability to relate to the average black family’s struggles that resulted from a legacy of Jim Crow and slavery. For a generation of white Americans that had little contact with black America in daily life, the apathy Thursday nights with the Huxtables created toward the experience of black struggle has been understated. The idea that if Cliff Huxtable did it you can too rang loudly in expectations of black progress. As written in the piece “White racism and “The Cosby Show,”

Still, considering that nearly all its performers are African American and that racism still befouls life in the United States, the mission of THE COSBY SHOW was difficult and its financial success remarkable. It had to represent race in a way that enabled audience members to feel good enough about themselves, sometimes for different and contradictory reasons, that they reliably returned every week, ready to attend to the ads of the corporations that paid hundreds of thousands of dollars a minute for access. By the time the show finished its first season on NBC in 1985, it deftly had won admission into millions of segregated European American homes.

Cosby’s popularity and skill was surely crucial to its success, but significant too was a critical aspect of his persona-he never raged or despaired. No doubt for many the show’s goodwill carried with it some acceptance for African Americans, a guess who’s coming to dinner? for the Reagan years. Yet as several critics have noted, the price paid by the makers of the Cosby Show for its jumbo audience was clear: silence on racism. “To have confronted the audience” about racism “would have been commercial suicide,” says Justin Lewis, who has studied viewer responses to the program (164). An active supporter of progressive politics, Cosby acknowledges that Cosby did not mention racism for fear of alienating white viewers (Graham). “I agree with critics who say it doesn’t do enough,” he says. … Yet in what seems both cause and effect of cultural productions such as The Cosby Show, polls show that most U.S. whites “no longer feel blacks are discriminated against in the schools, the job market and the courts” (Brownstein Ml) … As co-creator and executive producer of the show, Cosby insisted that it never highlight racial conflict. He says if it had done so even once, every white viewer would have felt “this was set up to make you feel like you’re the villain” (Graham). The success of THE COSBY SHOW with mass audiences of whites in the United States (and South Africa!) seems to have been dependent upon its refusal to include racism among its representations.

The general belief that supported the Cosby Show held that the series was a contrast to the display of violence, and poverty that had preceded it on shows like Good Times and the like. The aforementioned Ebony article delves into a critique that sets the Cosby Show against the infestation of crack cocaine, and the era of mass incarceration Ronald Reagan ushered in during the early eighties. Earlier this year the documentary I served as a producer on “Freeway: Crack in the System” aired on Al Jazeera and detailed this time period’s devastating impact on black America.

It has been stated by people from Don Lemon to Phylicia Rashad, the Cosby show was a visual of people they grew up around and recognized. It was a supposed representation of the black middle class life that had not been shown on television prior.

But, to this I have to say undoubtedly the Huxtables were presented as a wealthy black family, and not shown as middle class. We cannot fail to recognize this fact. I believe we have done just that as we remember their presentation every week in our homes by NBC. As stated in the piece above, “White racism and The Cosby Show” in reference to Cosby’s character, “significant too was a critical aspect of his persona-he never raged or despaired.”

To explain further, we can simply look at the home they lived in to support the statement on their financial position. When businessinsiders.com recently assessed the home the Huxtable’s lived in during the early 1980’s, they stated,

LOCATION: While viewers believed the Cosby clan lived in Brooklyn Heights, the real home was located at 10 Leroy Street in the West Village. THEN: In 1984, a Brooklyn Heights brownstone would have gone for around $700,000. NOW: A Brooklyn Heights town house would cost $5-$7 million, estimates Corcoran.

Giving this context in the early 1980’s normal home loans were given at a rate above 15 percent, a loan of this type would have been likely considerably higher. In addition, a prospective buyer would have to come with anywhere from 10-20 percent or more of the home value as the down payment.

On the low end this family would have had to put down over $100,000 in cash, and paid a mortgage of $8,000 a month in the early 1980s. That would be the equivalent of a $18,000 mortgage today. By any stretch of the imagination, that is not the story of the black middle class. In fact, as I showed in a piece earlier this year “America’s Financial Divide: The Racial Breakdown of U.S. Wealth in Black and White” today in present dollars according to a report by Credit Suisse only 5 percent of black American families even have $350,000 in total assets. So we can only imagine how small the number of black families that had access to $100,000 for a down payment was in 1984.

Relying on data from Credit Suisse and Brandeis University’s Institute on Assets and Social Policy, the Harvard Business Review in the article “How America’s Wealthiest Black Families Invest Money” recently took the analysis above a step further. In the piece the author stated “If you’re white and have a net worth of about $356,000 dollars, that’s good enough to put you in the 72nd percentile of white families. If you’re black, it’s good enough to catapult you into the 95th percentile.” This means 28 percent of the total 83 million white homes, or over 23 million white households, have more than $356,000 dollars in net assets. While only 700,000 of the 14 million black homes have more than $356,000 dollars in total net worth.

While America’s acceptance of the refuge the image of the Huxtables provided from the representation of black struggle is in some ways understood. The dynamic of black financial and social struggle that swirled around the show in working class African-American homes across the nation was still very real. The typical African-American reality was far different than the Cosby dream. With the Cosby show’s meteoric rise Americans of all hues slowly forgot this truth hidden behind the decadent veil of their multi-million dollar Brooklyn brownstone. As Ebony’s November issue brings this, and other discussions to the forefront we must enter the discourse being honest about the Cosby dream, and the African-American financial reality.

Antonio Moore is a former prosecutor in Los Angeles. He is also one of the producers of the documentary on the Iran Contra, Crack Cocaine Epidemic and the resulting issues of Mass Incarceration “Freeway: Crack in the System” broadcast on Al Jazeera. Mr. Moore has contributed pieces to theGrio, Huffington Post and Eurweb on the topics of race, mass incarceration, and economics.

— This feed and its contents are the property of The Huffington Post, and use is subject to our terms. It may be used for personal consumption, but may not be distributed on a website.

Continued: