Tens of thousands of protesters streamed out of New York City’s Washington Square Park on Saturday to protest the killings of unarmed black people by police officers, as part of the “Millions March NYC.” The crowd began to wind its way through Manhattan. A large labor union contingent was present, including members of the Communications Workers of America wearing red shirts and AFL-CIO supporters waving blue signs. In contrast to other marches over the past week, this large, orderly demonstration took place during the day. A number of families with children took part, and demonstrators followed a pre-planned route. The march made its way uptown to Herald Square, then looped back downtown, with thunderous chants of “Hands up…

Tens of thousands of protesters streamed out of New York City’s Washington Square Park on Saturday to protest the killings of unarmed black people by police officers, as part of the “Millions March NYC.“

The crowd began to wind its way through Manhattan. A large labor union contingent was present, including members of the Communications Workers of America wearing red shirts and AFL-CIO supporters waving blue signs.

In contrast to other marches over the past week, this large, orderly demonstration took place during the day. A number of families with children took part, and demonstrators followed a pre-planned route. The march made its way uptown to Herald Square, then looped back downtown, with thunderous chants of “Hands up! Don’t shoot!” and “Justice! Now!” echoing down Broadway. The demonstration culminated at One Police Plaza, the Lower Manhattan location of the New York City Police Department’s headquarters.

Organizers estimated that 30,000 demonstrators participated in the march. The NYPD told The Huffington Post that, as of the official end of the march, no arrests had been made.

Protesters held up 8 panels depicting Eric Garner’s eyes, created by an artist known as JR. “The eyes were chosen as the most important part of the face,” said Tony Herbas of Bushwick, an assistant to the artist.

Ron Davis, whose son Jordan was shot dead by a man in Florida after an argument over loud music, was at the head of the march.

“We have to make everybody accountable,” Davis told HuffPost. “You can’t continue to see videos of chokeholds, videos of kids getting shot in the back, and say it’s all right. We have to make sure we have an independent investigator investigate these crimes that police carry out.”

Michael Dunn, the man who killed Jordan, was convicted of first-degree murder and sentenced to life without parole in October. Davis said Saturday that Dunn’s conviction proves it’s possible that justice can be served in racially charged cases.

“We ended up getting a historic movement in Jacksonville,” Davis said. “We had an almost all-white jury, with seven white men, convict a white man for shooting down an unarmed boy of color.”

Also at the front of the march were New York City Councilman Ydanis Rodriguez and New York state Assemblyman-elect Charles Barron.

Matthew Brown, a 19-year-old who is African-American and Hispanic, marched down Broadway with his mother, aunt and other family members.

“I’m trying to support a movement that really needs young people like myself,” said Brown. “I’m here to speak for Mike Brown.”

The teenager said part of his motivation for making the trek from West Orange, New Jersey, with his family was his own personal experience. He’s encountered racist verbal abuse from police in Jersey City, he said, who have called him “spic” and monkey.”

Citing the cases of Michael Brown, Eric Garner and Tamir Rice, Brown said part of the reason he wanted to speak out was because of the way police represent encounters with African-Americans. “I just see so many lies after lies.”

He also attended the People’s Climate March in September. But this march felt more intense to him. “This is one that’s really affecting people on a deep, emotional level,” Brown said.

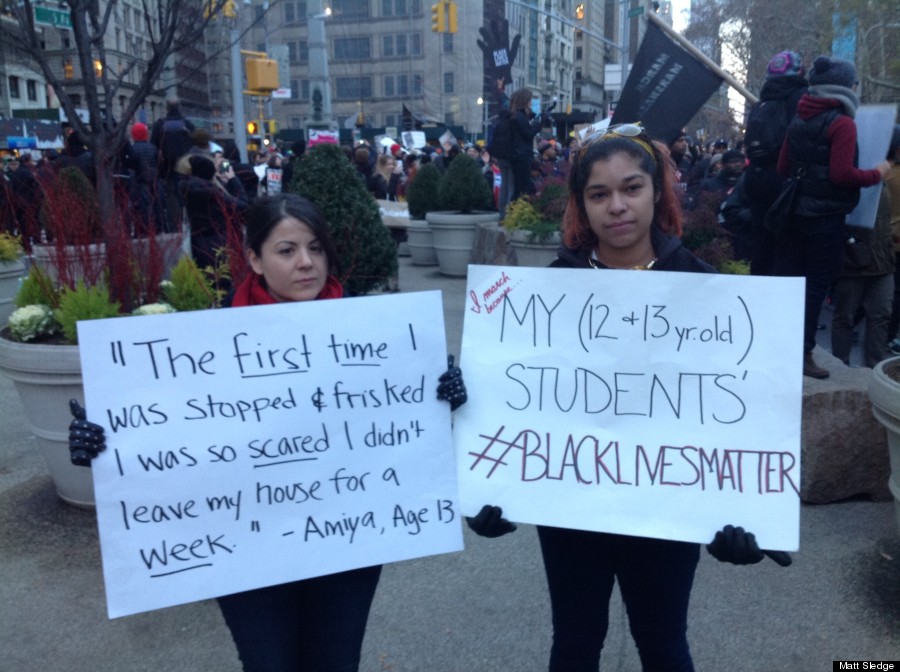

Krystal Martinez, a 23-year-old schoolteacher, said she attended the march to send a simple message: “I don’t want my students’ names chanted at any of these events.”

Because she teaches at a charter school that serves students from Bedford-Stuyvesant and Crown Heights, Martinez said, she was painfully aware of the challenges black youth face in interactions with police.

Martinez, a Harlem resident, pointed to a sign held by a colleague with a quote from a 13-year-old girl who had been stopped by police: “The first time I was stopped and frisked I was so scared I didn’t leave my house for a week.”

“Eighty-five percent of my students are black and this is their lives,” Martinez said, emphasizing that she spoke for herself and not her school. “I’m out here because of my kids.”

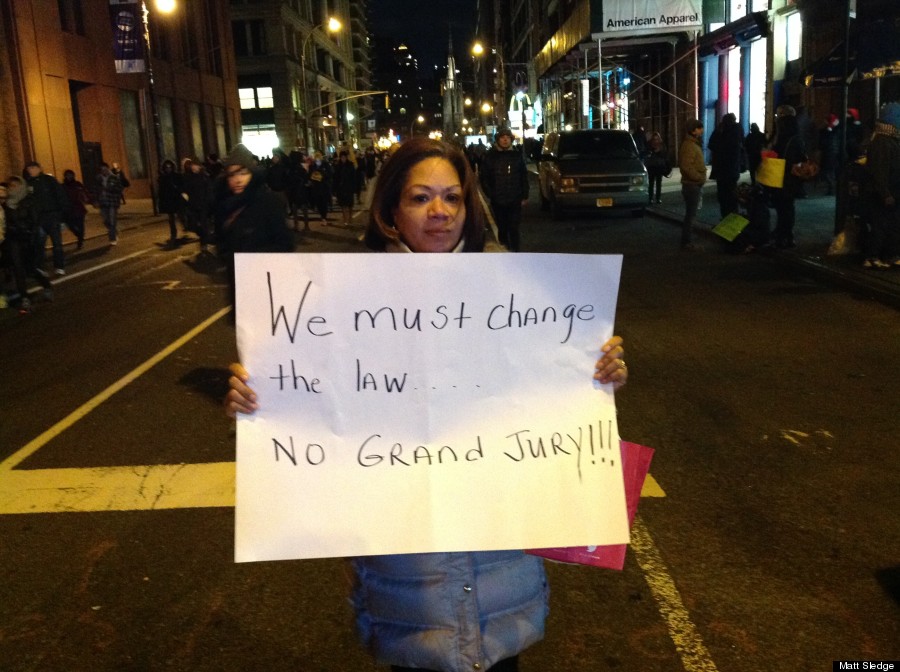

Some protesters arrived with concrete policy proposals. Marcia Dupree, a homecare supervisor, came bearing a sign that read, “We must change the law … no grand jury!!!”

“The root of the problem,” Dupree said, was the closeness between grand juries and police. In the wake of two grand juries’ decisions not to indict officers in the Michael Brown and Eric Garner deaths, the idea of abolishing the institution has gotten a lot of attention from both the media and policymakers, including the chairman of Missouri’s Legislative Black Caucus.

Dupree added that she’d never really considered herself much of an activist before. Serving on the board of her local library in Mount Vernon, New York, was “as political as I got.” But she said she has been moved to protest out of concern for her 13-year-old daughter — who was marching in crutches by her side — and her 21-year-old son.

“I feel like I need to stand up,” said Dupree. “It could be my son.”

At times, the march blurred surreally with Santacon — the sloshy daytime celebration of Christmas (and drinking) that New Yorkers hate on every year.

A number of Santacon participants joined the march. Others were less enthusiastic. “I love cops, seriously,” one man in a Santa cap told an impassive officer. “I hate these people.” Then he walked off with his fellow revelers.

Saturday’s day of action came in response to two separate grand jury decisions not to indict police officers for killing unarmed black men. On Nov. 24, a St. Louis County grand jury voted not to indict Police Officer Darren Wilson, who fatally shot Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri. Less than two weeks later, a Staten Island grand jury declined to indict Officer Daniel Pantaleo, who killed Eric Garner by putting him in a chokehold.

Brown’s death on Aug. 9 triggered months of protests in Ferguson against police killings — protests that have since spread nationwide.

One group of marchers turned into a street protest choir, singing, “We’re not gonna stop, until people are free.”

Beneva Davies, a 23-year-old Harlem resident who lent her voice to the group, said the most singing she usually does is in the shower.

“It’s not really about your voice,” Davies said. “It’s about your voice, right?”

Davies’s family hails from Sierra Leone and Ghana, and she grew up in Massachusetts. Sometimes, she says, she sees a “disconnect” between recent African immigrants and the African-American descendants of slaves.

But she tries to push back against that disconnect, she said, because “at end of the day it’s what you’re seen as, right?”

Davies saw the march as her chance to answer the question of what she would have done if she had been alive during the civil rights protests led by Martin Luther King Jr.

After hundreds of years of slavery, Jim Crow and more, Davies said, “People continue to get killed. … It’s frustrating. We have to be here so people can see it.”

Sebastian Murdock contributed reporting.

This story has been updated.

Continued here:

Tens Of Thousands March On NYPD Headquarters To Protest Police Killings