“Any Number of Preoccupations,” 2010 Artist Lynette Yiadom-Boakye paints, almost exclusively, portraits of black figures. More often than not, the person is juxtaposed against a black background, or at least one mired in darkness, allowing the features of the foreground to camouflage with their surroundings, creeping towards invisibility. “Where painters including Barkley L. Hendricks, Kehinde Wiley and Mickalene Thomas have taken a celebratory, triumphant and sometimes showy approach to the black subject, Ms. Yiadom-Boakye makes it nearly invisible,” Karen Rosenberg wrote in 2010. “She favors a dark, near-monochromatic palette and loose, even sloppy brushwork. Faces are inchoate, bodies phantomlike. Her figures don’t…

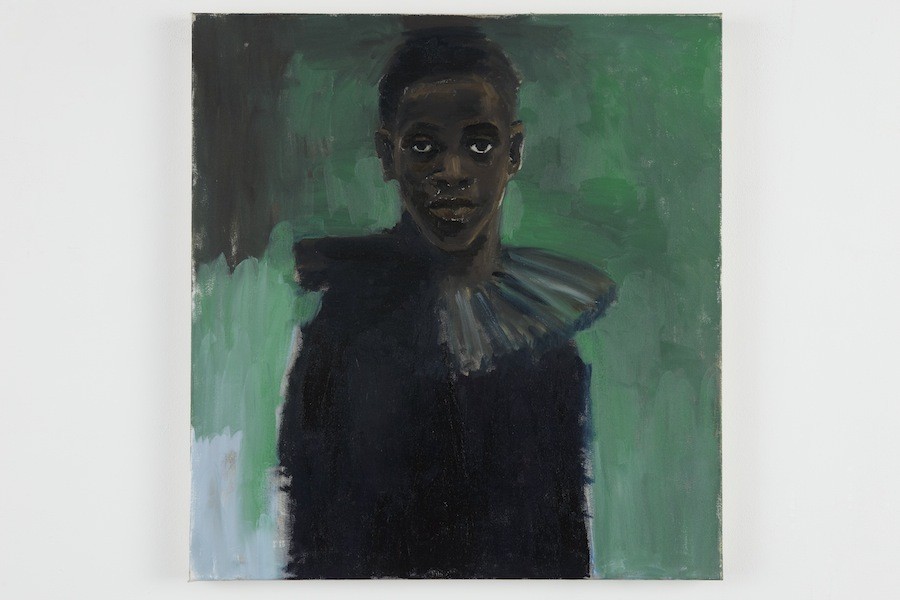

Artist Lynette Yiadom-Boakye paints, almost exclusively, portraits of black figures. More often than not, the person is juxtaposed against a black background, or at least one mired in darkness, allowing the features of the foreground to camouflage with their surroundings, creeping towards invisibility.

“Where painters including Barkley L. Hendricks, Kehinde Wiley and Mickalene Thomas have taken a celebratory, triumphant and sometimes showy approach to the black subject, Ms. Yiadom-Boakye makes it nearly invisible,” Karen Rosenberg wrote in 2010. “She favors a dark, near-monochromatic palette and loose, even sloppy brushwork. Faces are inchoate, bodies phantomlike. Her figures don’t really inhabit their clothes, or the spaces around them.”

The artist’s enigmatic works are now on view in “Lynette Yiadom-Boakye: Verses After Dusk,” at London’s Serpentine Gallery.

Yiadom-Boakye was born in London in 1977, the daughter of two nurses born in Ghana. She attended Falmouth College of Art and received her MA at the Royal Academy Schools. She began working full time as an artist in 2006, after winning an Arts Foundation award, and in 2013, received a new rush of widespread attention after being shortlisted for the Turner prize.

The artist’s portraits, in a strange way, communicate they’re not to be trusted. And for good reason. The images, rather than highlighting specific individuals in time and space, conjure fictitious presences, people that never were, outside of the realm of canvas and paint. The artist uses no photographs or preliminary sketches to create her startlingly realistic portraits. The detailed depictions are concocted entirely in the imagination, and executed in paint during the course of a single day.

The longer you look into the eyes of Yiadom-Boakye’s mythical subjects, the more their impossibilities float to the surface. Particularities place each subject in multiple eras, locations, even genders. As Jennifer Higgie wrote in Frieze: “Despite the fact that there is something determinedly average about these people –- who, apart from the children, tend to be neither very young nor very old, seemingly neither rich nor poor –- they exist in atmospheres touched by a compellingly faint frisson of something not quite explained.”

As the artist explained to New York Times Magazine in 2010, she does not paint her subjects. Rather, the subject is paint itself. “Painting for me is the subject. The figures exist only through paint, through color, line, tone and mark-making.”

Although her characters defy any singular origin, Yiadom-Boakye’s style has clear roots in the trajectory of Western art history. Her works contain the darkness of Francisco de Goya, the flurrying movement of Edgar Degas, the slow leisure of John Singer Sargent, the rough handling of Édouard Manet. Of her influences, Yiadom-Boakye told The Guardian: “I wasn’t intimidated by those painters. It made it easier: there was so much I could look at and learn from.” Through channeling these historical giants, Yiadom-Boakye raises awareness of the lack of black representation throughout the history of art.

“Historically, portraits have conveyed the wealth and authority of their subjects through poses projecting confidence and strength and through clothing, accoutrements and surroundings used strategically to indicate social hierarchy,” Amira Gad writes in an essay accompanying the exhibition. “Commissioning portraiture was a symbol of status, and only the elite were entitled to be immortalized within the ranks of historical painting. With Yiadom-Boakye’s layering of references, her paintings draw attention to the flawed perception of race in historical paintings. In depicting black subjects doing everyday things, she advocates both the normalcy and intricacy of blackness.”

“Lynette Yiadom-Boakye: Verses After Dusk,” will be on view at Serpentine Gallery until September 13, 2015.

— This feed and its contents are the property of The Huffington Post, and use is subject to our terms. It may be used for personal consumption, but may not be distributed on a website.

Continued:

Lynette Yiadom-Boakye’s Enigmatic Portraits Show Black Figures That Never Were