This piece originally appeared on Bright, Medium’s publication about education innovation. To see more stories like this, head over to Bright and hit the “Follow” button – or share your own story. In late April, Indiana state legislators voted to increase spending in wealthy suburban schools, while reducing funding for some poorer urban ones. For years, Indiana has spent more per student in its poorest school districts (i.e., those with the highest percentage of students living below the poverty level) than on those in its wealthiest. Supporters of the measure say that wealthier schools have long “suffered” from disparate funding, and that the new budget will be more balanced. Many people are, understandably, angered by this …

This piece originally appeared on Bright, Medium’s publication about education innovation. To see more stories like this, head over to Bright and hit the “Follow” button – or share your own story.

In late April, Indiana state legislators voted to increase spending in wealthy suburban schools, while reducing funding for some poorer urban ones. For years, Indiana has spent more per student in its poorest school districts (i.e., those with the highest percentage of students living below the poverty level) than on those in its wealthiest. Supporters of the measure say that wealthier schools have long “suffered” from disparate funding, and that the new budget will be more balanced.

Many people are, understandably, angered by this decision. Poor students in the United States already have it tough. They tend to lag in most measures of academic achievement. They score lower on standardized tests than their wealthier peers. They are more likely to drop out of school, and less likely to go to college. Indiana’s decision may only exacerbate these disparities.

But if you look through the data, you’ll find that – contrary to conventional wisdom – more money doesn’t necessarily mean better education. Money may be a good start, but doesn’t on its own guarantee great educational outcomes.

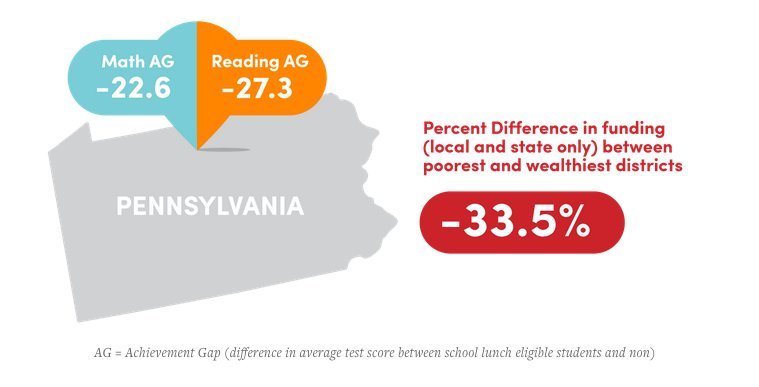

Let’s compare Indiana and Pennsylvania. The poorest school districts in Pennsylvania receive 33 percent less funding per student than the state’s richest school districts, according to the latest data from the Department of Education. Since students from poor families generally need more support than students who don’t, that’s unconscionable.

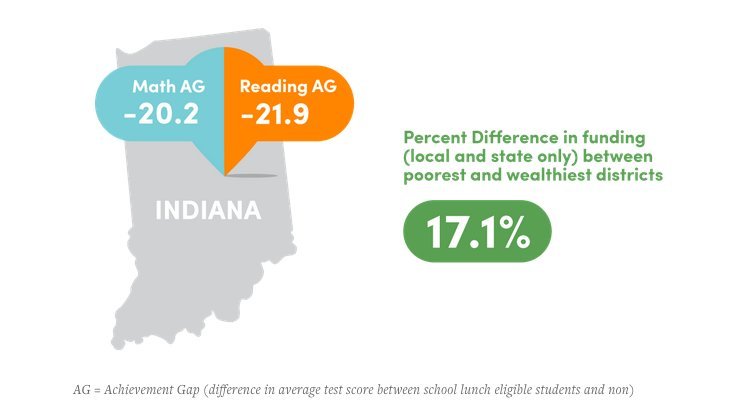

In stark contrast, Indiana (at least until very recently) spends 17 percent more per student in its poorest districts than it does on those in its richest. This might lead you to conclude that poorer students do better there than in Pennsylvania. But that’s not altogether true – at least not in terms of the socioeconomic “achievement gap,” or how well poor students perform academically relative to their wealthier peers.

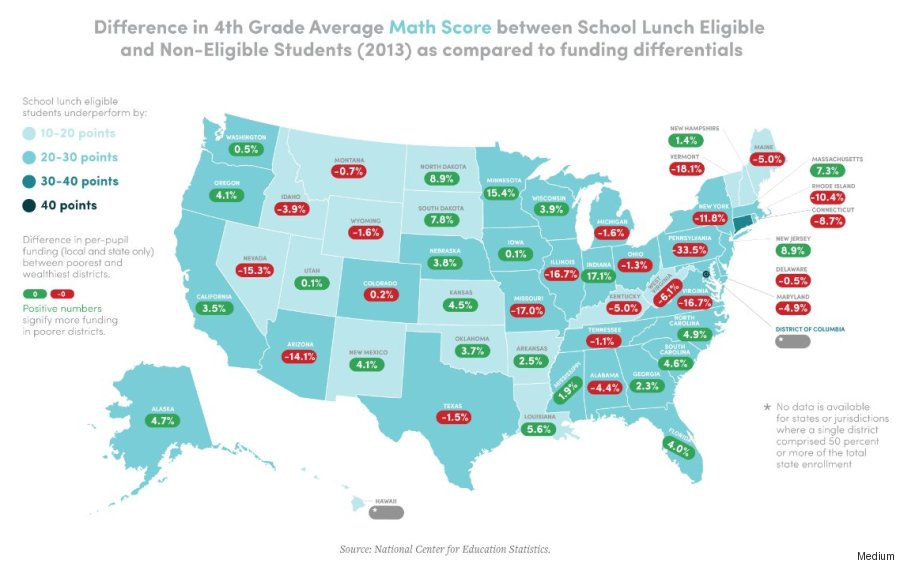

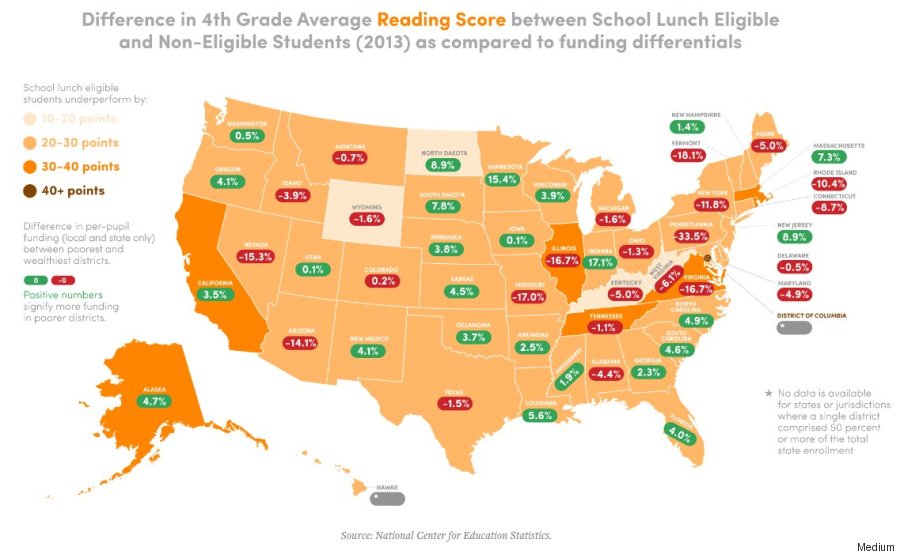

There are different ways to evaluate this achievement gap, but the most common – and perhaps controversial – is how students perform on standardized tests. According to the latest results from the National Assessment of Educational Progress, students who qualified for the national school lunch program (a common measure of poverty) in Indiana scored 20 points less on average than wealthier students in math and 22 points less in reading. In Pennsylvania, those numbers were 23 and 27 points, respectively.

The achievement gap is smaller in Indiana, but not by much. It’s certainly not what you’d expect given the spending differential. Indiana may be a role model in terms of its “pro-social” spending – but if the Hoosier State wants to improve student outcomes, it will have to do more than throw money at poorer students.

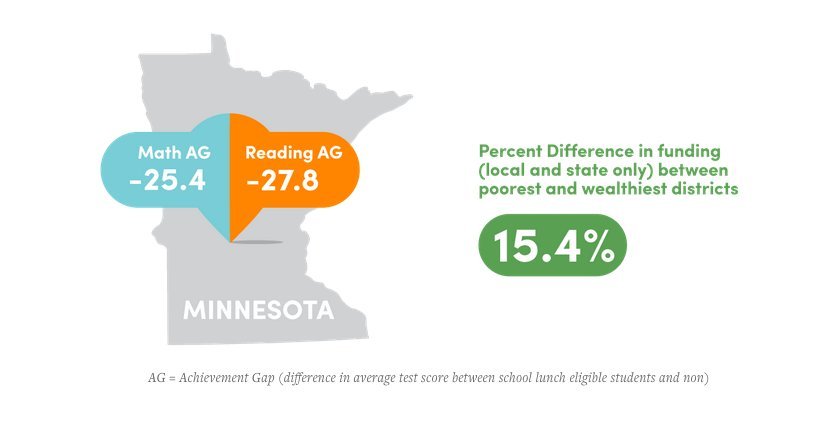

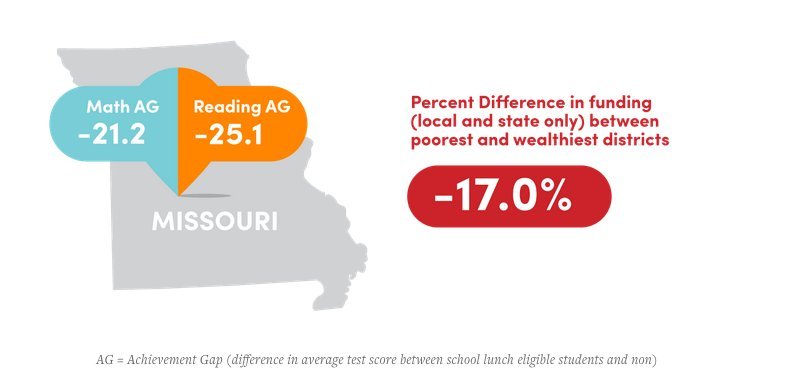

Minnesota and Missouri are another example of the hazy relationship between spending and achievement equality. Despite spending 15 percent more per student in its poorest districts than in its wealthiest, Minnesota had the seventh largest disparity in math scores in the country. Its disparity in reading was only slightly better than the national average. In contrast, Missouri spent 17 percent less per student in its poorest districts than it did in its wealthiest, but had a smaller than average disparity in both reading and math.

When you include federal money, the spending gap closes in almost every state; but the overall picture remains the same. Some of the country’s worst achievement gaps are in states that spend substantially more in their poorest districts than in their wealthiest ones.

That’s because, when it comes to equity in education, spending is just one piece of a much larger, more complex puzzle. There is a whole slew of other factors that help determine how well poor students do in school – like teaching quality, curricular rigor, parents’ level of education, class size, school safety, access to healthcare, parent involvement, and even birthweight.

“I am a firm believer that multiple [types of] data should be used in looking at achievement,” said Dr. Nicole Poncheri, the principal of Cole Manor Elementary School in Norristown, Pennsylvania. “One measure cannot fully tell the story of why we see certain gaps in some areas.”

Poncheri’s students have done exceptionally well on standardized tests. In 2013, low-income students at Cole Manor – who constitute 80 percent of the school’s population – outperformed low-income students in the rest of Pennsylvania, in terms of statewide reading and math test scores. There was less than a 10 percent gap between low-income Cole Manor students and their wealthier counterparts. That’s compared to a gap of almost 30 percent in the rest of Pennsylvania (and in Indiana, for that matter).

What did they do differently? Poncheri emphasized that equitable spending is key to equity in achievement. Without Title I funds –that is, supplemental federal funding for schools with a high percentage of low-income students – she said that some key positions in her school, including “instructional support teachers” that help classroom teachers identify and support struggling students, would be vacant.

But she believes that the non-financial aspects of her school’s approach, like the school culture and strong communication and collaboration among staff, matter more.

“[Classroom teachers] plan together, discuss student needs on a daily basis, analyze data, and work integrally with our instructional coaches, special education teachers, and ELL [English Language Learner] faculty,” said Poncheri. “We do not have staff meetings for the sake of meeting or data reviews simply to comply. When we do these things, we always take time to reflect upon how it is making the school more effective – and how it ‘trickles down to the classroom level.’”

To many education experts, the intense focus on school spending may obscure other crucial factors to student achievement – thereby reducing a multifaceted issue to a dollar figure. “Anyone who believes that money alone will make the difference isn’t paying attention,” said Jonathan Cetel, Executive Director of PennCAN, a Pennsylvania-based research and advocacy group. “Additional funding must be paired with meaningful reforms to ensure those resources are optimized. Camden [New Jersey] spends $27,500 per-pupil, yet only three high school students out of the 882 who took the SATs in 2012 were ‘college-ready.’ Not three percent. Three students!”

One could argue that, since dollar figures are easier to measure than, say, school culture, it is easier and more realistic to focus on school spending.

Admittedly, the achievement gap may not be the best measure to look at differential student outcomes. If a state “closes its achievement gap,” it could mean two very different things: that poor students are doing better or that wealthier ones are doing worse. The former is desirable; the latter is not. Nevada, for example, has one of the smallest achievement gaps in math. But that’s because non-poor students there underperform relative to non-poor students in the rest of the country.

The data also don’t tell us anything about long-term effects of school spending. Increased funding may not lead to better performance in the short term, but it could have profound effects later in life. A study published last year found that for poor students, a 20 percent increase in annual per-pupil spending had several desirable outcomes. These students completed nearly an additional year of school, earned 25 percent more in job wages, and were 20 percent less likely to be poor. Interestingly, there was no effect on students who weren’t from poor families.

It is unacceptable that some states exacerbate differences in achievement by spending less on the kids who need the most help. If education is supposed to be the great equalizer in the United States, we should spend at least as much money on poorer students as we do on wealthier ones. But let’s make sure policymakers don’t stop there, and that children from disadvantaged backgrounds get the kind of holistic support they need to succeed in school.

— This feed and its contents are the property of The Huffington Post, and use is subject to our terms. It may be used for personal consumption, but may not be distributed on a website.

Source article –

It Is Going To Take A Lot More Than Money To Close The Achievement Gap