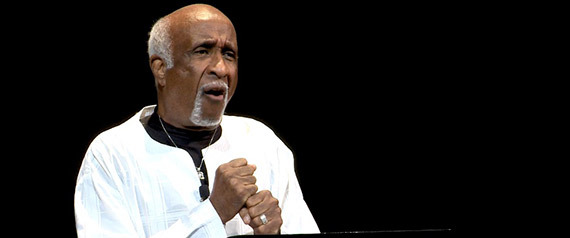

This story was written and performed by Ernest McMillan for the live, personal storytelling series Oral Fixation (An Obsession With True Life Tales) on Dec. 8, 2014, at the Wyly Studio Theatre in Dallas. The theme of the show was “Outside the Box.” “There were many big players in the American civil rights movement,” says Oral Fixation creator and director Nicole Stewart. “We know who those were. But there were also thousands of people playing smaller roles — who continue to fight the good fight to this day — and one of them is Ernest McMillan, who dodged the draft and became a Black Power fugitive in West Africa in the ’60…

This story was written and performed by Ernest McMillan for the live, personal storytelling series Oral Fixation (An Obsession With True Life Tales) on Dec. 8, 2014, at the Wyly Studio Theatre in Dallas.

The theme of the show was “Outside the Box.”

“There were many big players in the American civil rights movement,” says Oral Fixation creator and director Nicole Stewart. “We know who those were. But there were also thousands of people playing smaller roles — who continue to fight the good fight to this day — and one of them is Ernest McMillan, who dodged the draft and became a Black Power fugitive in West Africa in the ’60s. His is a powerful story of running, hiding, and ultimately coming home. Read it here, and watch his performance below.”

The summer of 1969 was the hottest of my life.

My world had already been scalded by the murders of the four Birmingham girls, of Malcolm X, Dr. King, and the three civil rights workers slain in Mississippi, and by the unpublicized murder of George Bess, a dear friend and comrade killed there a month later. And now, after the call for black power, I and many activists were facing even more intensive attacks as J. Edgar Hoover’s strategy for “counterinsurgency” unfolded.

In 1969 alone, there were more than two dozen police executions, scores of movement leaders imprisoned, others forced into exile. In Dallas, I felt the intense concert of repression so much so that Kwesi and I fled fearfully into Canada with the FBI on our trail. There we changed our identities and made our way together into West Africa, hoping to gain political asylum in Guinea. I regarded Kwesi as my younger brother. He was a butcher by trade and had entered the civil rights movement less than a year before. While riding a bus home from work, he passed a demonstration I led boycotting a chain of 10 ghetto-gouging convenience stores in South Dallas. He was intrigued, got off the bus, joined our picket lines, and never went back to his old job. He became one of a few men and women who gave up their jobs, families, and old routines to join me in the civil rights movement.

Several months after venturing through France, traversing bumpy jungle roads on crowded lorry trucks through Senegal, Mali, and Burkina Faso, we wound up in Ghana. There we miraculously found hospitality, new friends, shelter, and sustenance — but still not our target destination. Soon, Kwesi and I were tiny dots in the midst of thousands other dots, non-Ghanaians, on a road to nowhere. The newly elected prime minister of Ghana decided to expel all aliens with his Alien Removal Act. The impact of his newly enacted policy was catastrophic. Hundreds of thousands, without regard to their individual talents, skills, or circumstances, were forced to pack and leave at once. Kwesi and I, fugitive U.S. citizens, had to hit the road, too.

Our first and second days among the exodus were spent stuck on an invisible borderline between two nations, in no-man’s land awaiting the decision of unknown powers. Ghana wanted us out, and the Ivory Coast refused us entry.

While leaning on the shady side of our truck, drinking, then spitting out a nasty-tasting oily liquid from a reused Coke bottle, I heard the sound of one lorry cranking up in the distance, then another, then a swarm of engines churning. Sensing movement afoot, I joined the horde, an unending caravan of trucks, bikes, pedestrians, and ox-drawn carts that had been motionless throughout the night. Without fanfare or announcement, the border gates opened.

As refugees routinely subject to the cruelties and whims of any and all, there were angels also, mysteriously appearing: a listening ear, a kind word, a meal here, a floor there, and indispensable travel guidance and advice — all quiet yet mighty blessings. Even Liberia — a headquarters for several giant U.S. corporations, one of the world’s more impoverished nations, run by descendants of U.S. slaves and its micromanaging dictator — was no exception to the bountiful presence of miracle workers. There, and despite Liberia’s horrendous environment, we learned affirming and invaluable lessons from some of its more common, everyday inhabitants.

One endearing angel was “Maw” Mary, a mother to many, including her two new American sons. She agreed to cook our suppers, a meal she too often purchased upfront as our money trickled in from odd jobs or from home. She was a robust, no-nonsense village leader with an uncanny authority to resolve conflicts and disputes. She was the village arbitrator, be it of marriage conflict or neighborhood feud. Kwesi and I witnessed these proceedings, called “palabra.” The parties would state their cases, then rebut or interject sentiments in streaming emotions. The exchanges would rage, arms flailing, spit flying, and tempers skyrocketing. Maw Mary would render her distinct decision calmly. The two parties would accept her pronouncement and walk away in acceptance, sometimes in an embrace. I learned through Maw Mary that two people, even with the most emotionally charged and radically opposed personal differences, could indeed work through them without violence or evasion.

I came close to death in Liberia, and she saved my life. I contracted malaria out of the stupid notion that, as an African, I did not need any malaria prevention medications. Late one evening, I felt very weak and feverish. Maw Mary took quick action, surrendered her bed to me, repeatedly dousing my body in rubbing alcohol to break the fever, prepared and administered hot soups, prayed over me, and stood by my side day and night for more than three days. I was in a delirium most of the time. It was so real: Someone or something with neon, glowing-red eyes gripped my spine, twisting it in wretched contortions. I was waging fisticuffs in a half-consciousness with some monster that sought to claim my soul. I would reel back and forth, slipping in and out of awareness, catching a glimpse of Maw Mary rubbing alcohol onto my body or singing some mournful song seemingly from afar, as I battled with this spine grabber and eventually warded off a deadly sickness.

After some eight months traversing the Niger River valley, the reality finally struck us like a lightning bolt from a cloudless sky: It was time to go home. Our stark, indisputable differences appeared the moment we opened our mouths. We were like fish flopping on a shore, dying out of the water. It was time to go home, regroup, reconnect, rejoin the movement, do work from within.

I turned for help from a newfound friend in Monrovia. He was Rev. John, a Baptist preacher who understood our general plight and had ministered to us with food, housing and moral support. He was a brave, forthright man. It took little time for me to remove any doubts about him or his integrity.

In no time did he respond to our pleas for help in returning home and promised to get us on a cargo ship bound for New York Harbor. The catch was that we would know of the ship’s arrival only minutes before it neared and just a couple of hours before it would refuel and depart for New York. He’d arrange documents and money for a couple of bunk beds for our five to seven days at sea. We decided to go for it.

It was late morning when we got the news. The ship would enter port that afternoon. We had been packed for days, had said our goodbyes to the point when people were now giving us that “Yeah, sure you’re leaving” look. We tried to kiss Maw Mary goodbye, but she pushed us away, saying, “Go now.” She wasn’t up for that mushy stuff. We got a ride to the docks with the reverend. He waited with us as the ship docked. Rev. went to the ship alone, carrying our papers and documents to its captain. We waited anxiously near his car. He returned in a rush, a scowl on his face. He said we needed shot records to reflect yellow fever immunizations. If not, then the ship would be quarantined in New York Harbor, and the captain could not afford that. Rev. told us that he’d take care of it, drive back into town and get the proper stamp and signatures and we’d be off.

We waited. The sun began to lower into the sea. We paced. We walked up to the ship and raised our arms and hunched our shoulders as the crew began to stir more deliberately, readying the ship for departure. Then the ship’s motor rumbled. The last crew member went aboard, and the loading ramp was lifted. The boat began moving, and we shouted, “Hey, wait a minute! We’re coming aboard!” The ship slowly moved away, separating itself from the wharf and from us.

We turned to see Rev’s car entering the harbor. I screamed at the ship, tears rolling down my cheeks. I threw my baggage in the air, took off my shirt, and waved it at the ship’s fading silhouette. By the time Rev. got out of the car and handed us the documents, it was gone, swallowed by the waves. I sat on the ground, my hand over my face. Rev. sighed deeply, saying, “Don’t worry. There’s still another way.” A few weeks later, Kwesi and I flew nonstop from Monrovia to New York, walked through customs and security at JFK International Airport, and safely exited onto the chilly streets of New York City. Rev. had made sure of his promise. Now it was time for me to make good of mine: to rejoin the movement and work for peace and justice.

I remained free for the next nine months, working on that promise, and though I was imprisoned the following 38 months, it was still a promise kept. Today, despite shifting tides and drastically alternating circumstances, that same promise remains a yearning to fulfill.

Visit source: