While several business executives were preparing to sleep outside on a cold Detroit night to raise money for a youth homelessness organization, two miles away at a downtown gallery opening, the mood was festive and warm. But the artists mingling with the crowd would understand the execs’ plight — they were all formerly homeless themselves. Keith Jenkins is one of the photographers who showed his work in the “Through Our Eyes” exhibition last month. The event, held at Swords into Plowshares Peace Center and Gallery, was the culmination of a three-month PhotoVoice class that encouraged participants to document things that related to their health. For the class, students were given digital cameras to keep. Their work…

While several business executives were preparing to sleep outside on a cold Detroit night to raise money for a youth homelessness organization, two miles away at a downtown gallery opening, the mood was festive and warm.

But the artists mingling with the crowd would understand the execs’ plight — they were all formerly homeless themselves.

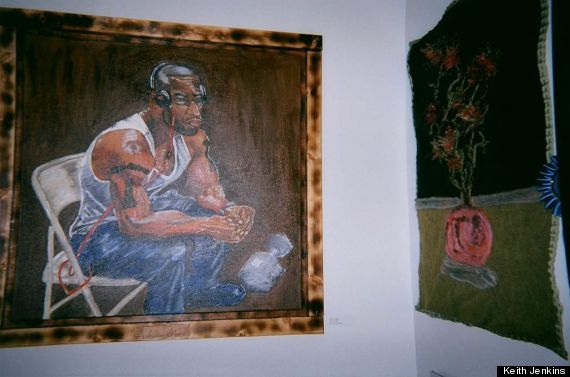

Keith Jenkins is one of the photographers who showed his work in the “Through Our Eyes” exhibition last month. The event, held at Swords into Plowshares Peace Center and Gallery, was the culmination of a three-month PhotoVoice class that encouraged participants to document things that related to their health. For the class, students were given digital cameras to keep. Their work was shown in three exhibitions.

“The class made me feel alive,” Jenkins told The Huffington Post. “I didn’t used to really talk, I’d keep to myself.”

Jenkins lives in the Bell Building, an initiative of the Neighborhood Service Organization to provide housing for some of Detroit’s estimated 16,000 homeless individuals.

For the PhotoVoice project, NSO teamed up with Oakland University in Rochester Hills, Michigan, to conduct a photo class for a group of Bell Building residents. The institution sought to study the participants’ experiences with health and wellness, as well as the barriers they face with seeking care.

“Photovoice,” a methodology first used by researchers in the 1990s, is used to get an understanding of a specific community’s concerns, particularly when it comes to health issues. Participants are given cameras to document particular issues and their lives in general. Researchers learn from the images and the discussion about them under the premise that the population under consideration will have the best knowledge of their circumstances.

At the exhibition, PhotoVoice student Lucretia Gaulden showed two photos, named “Day” and “Night,” of the exterior and interior of an old store. She said that, together, the pictures reminded her of herself.

“Because I’m happy-go-lucky on the outside,” she said, but “I can feel like a big blob of yucky on the inside.”

|

|

Gaulden has battled with depression but has recently been able to get treatment and medication. During a class discussion, when Gaulden explained the pictures represented her happy exterior hiding inner feelings of depression, others said they felt the same way.

“That picture is a lot of us,” she said, “because we’re smiling on the outside. It don’t necessarily mean that we’re clean. Yeah, we are junky and messed up on the inside, … but a lot of us are too scared to say that’s exactly how we are.”

Tia Cobb, interim director for NSO Homeless Recovery Services, said the class had empowered students to better articulate themselves and advocate for their needs.

“We could see the light just turn on and shine with each individual who did the program,” she said.

One of Jenkins’ photos, called “Memories,” depicted a painting of a man sitting in a chair listening to music. The man reminded Jenkins of his younger self, as well as his mother’s death.

“I was thinking about that and all the problems I had coming up, coming through my life, and it helped me with respecting myself more than what I used to,” he said.

The 155 units in the Bell Building provide housing for adults with documented mental health issues who were previously homeless. Tenants pay 30 percent of their monthly income for the $690 monthly rent of the furnished, single-bedroom apartments. A resident who’s bringing in $200 a month, for example, would only play $60 in rent. If someone has no income whatsoever, he wouldn’t have to pay anything.

NSO offers the residents health services and life skills classes. Each resident has a caseworker to help with his or her individual goals, whether that’s seeking addiction treatment, receiving eligible benefits or attending school. Currently, about 30 percent of tenants are employed and 15 percent are in education or skill training programs.

“What we believe is that we house folks first,” Cobb said. “Once we get you housed and stabilized in a living situation then we can begin to work with you on whatever your needs are.”

Their approach differs from some other programs that have stipulations, like requiring participants be drug-free.

“A lot of people can’t do that on their own, because they don’t have anyone that is helping them to navigate, get them through the barriers that might be in the way,” Cobb said.

Before 39-year-old Gaulden came to the Bell Building in 2012, she had been in prison for 12 years. When she was released, the world she remembered had changed drastically. She knew few people and was homeless for a year.

Now that she has a place to live and has worked on health issues, NSO is helping Gaulden with her goal of finding her two youngest children, who were toddlers when she went to prison. She hopes they can enter a different program for families and live together. (Gaulden is close with her 22-year-old daughter, who lives in another state.)

She also wants to learn how to drive, and no longer has qualms about going to school since speaking at Oakland University through PhotoVoice.

“I accomplished [the photo class], so that means that I can accomplish many more steps,” Gaulden said.

Both Gaulden and Jenkins help out around the Bell Building.

“I don’t see it as me volunteering, I see it as me not going back into that depressed mode, to where I was,” Gaulden said. “I don’t want to go back to the person I used to be, because I like the person that I am now.”

NSO hopes to continue the PhotoVoice program in the future depending on funding.

Original post:

How Giving Cameras To Formerly Homeless Detroiters Also Gave Them A Voice