Family historians tracing black family ancestries love wills and probate records. Why? Because these seemingly dry and bloodless documents are full of priceless information about our enslaved African American ancestors. Probate records document what people owned, who they loved, and what was really important to them. In fact, wills and probate records are often the only written documentation in which enslaved persons are listed by their first names. When paired with the surname of the person who registered the probate record, sometimes we can, almost miraculously, retrieve the lost identity of your ancestor who was enslaved, by piecing together their …

Family historians tracing black family ancestries love wills and probate records. Why? Because these seemingly dry and bloodless documents are full of priceless information about our enslaved African American ancestors. Probate records document what people owned, who they loved, and what was really important to them. In fact, wills and probate records are often the only written documentation in which enslaved persons are listed by their first names. When paired with the surname of the person who registered the probate record, sometimes we can, almost miraculously, retrieve the lost identity of your ancestor who was enslaved, by piecing together their first and last names.

More than 170 million pages of probate records were recently posted on Ancestry. Many of these records can help descendants of the nearly 90 percent of the enslaved African American population in 1860 discover the names of some of their enslaved ancestors, who can be extremely difficult to find. Remember that slaves were property and were almost never listed by name in census records. But they were listed by names in wills and probate records, because they were considered “property” and had to be identified in some way to be transferred to another “owner.” (While most of us were raised to believe that President Lincoln freed the slaves through the Emancipation Proclamation, all of the slaves were finally freed by the ratification of the 13th Amendment in December, 1865.)

Because slaves were considered personal property, they are often named in probate files, which include wills, inventories, estate distributions, and related documents. In these records, you have a greater chance of finding at least a given name in association with the slaves who were part of someone’s estate than you would in, say, the slave schedules that were part of the 1850 and 1860 federal censuses, which listed the enslaved by gender, age, and color. In some cases, you’ll find much more. Let’s examine a few cases.

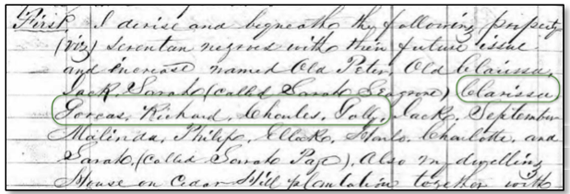

The will of William T. Hopkins names the following 17 slaves whom he is bequeathing to his wife:

First, I desire and bequeath the following property viz seventeen negroes with their future increase and increases named Old Peter, Old Clarissa, Jack, Sarah (called Sarah Seagrove), Clarissa, Dorcas, Richard, Charles, Polly, Jack, September, Malinda, Philip, Ellick, Hinto, Charlotte, and Sara called Sara Page, also my dwelling house on Cedar Hill Plantation…unto my Wife Elizabeth H. Hopkins to have and to hold the same during her widowhood.

The two Sara(h)s have last names included, which is extraordinarily unusual, and is thus extremely helpful to their descendants searching for lost members of their family trees.

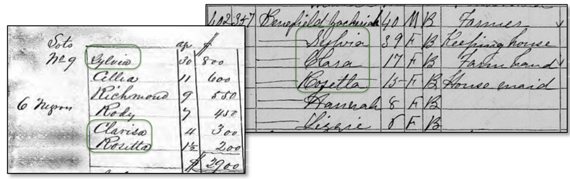

Let’s look at a second example: in the 1833 inventory of William’s father Timothy’s estate, the slaves appear to be listed by their own family groupings. Whether they were family by blood or family thrown together by circumstances we don’t know, but in looking through the groupings in Timothy’s estate, we see some of the same names in the same order that they appear in William’s will, which was written in 1843. The identical order and the values assigned to each slave in Timothy’s inventory points to a likely family structure, with working age adults, especially males, being valued higher and young children and the infirmed valued lower, just as we would expect.

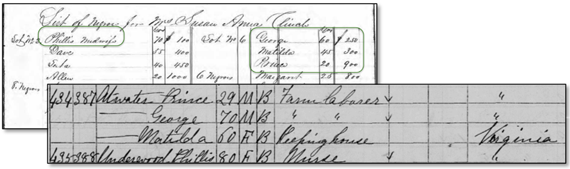

William T. Hopkins’ 1856 estate distribution also grouped slaves into “lots” and goes a step beyond his father’s inventory by providing their age and, in some cases, their occupations and infirmities. Its proximity to the 1870 U.S. Federal Census makes it possible for us to trace forward several groups of people listed as part of his estate fourteen years later, now living as freed people just five years after the end of the Civil War. Among the slaves given to his daughter, Susan Anna Clinch, we find Phillis, a midwife, and George, Matilda, and Prince Atwater now living next door to one another in 1870, still in Camden County, Georgia. Phillis now lists her occupation as “Nurse” at age 80.

And Sylvia, Clarisa (Clara), and Rosetta from Lot No. 9 are now living in the same household with Zachariah Benefield . While there is no one named “Zachariah” listed in William’s estate, he may have been enslaved on a neighboring estate, or they may have married after emancipation (the most likely scenario, given the age gap between Rosetta and Hannah).

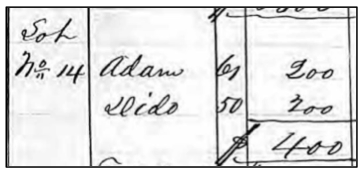

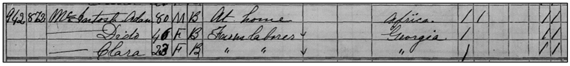

Another older couple also appears in the 1870 census in Camden County – Adam and Dido from lot 14. While both ages are off somewhat, and Dido’s is off enough to consider that she may be Adam and the older Dido’s daughter, the names are unusual enough that when paired together, that seems to indicate that they are family. Extraordinarily, Adam indicates that he was born in Africa!

Records like these don’t just help us identify the names of our ancestors, as significant as that discovery is. In some cases, they also hint at the regard in which they were held, and in the latter example below, a fact about the history of relationship between a master and his slaves. For instance, another provision in William T. Hopkins’ estate spelled out that,

Fourth. I request my executors to give my driver Jerry one suit of good broadcloth as a token of my regard.

Fifth. I request my executors to give March, Bill, and Clarissa being among the first slaves owned by my father, one suite of fine satinette each for the men and a dress for Clarissa which should cost the same amount.

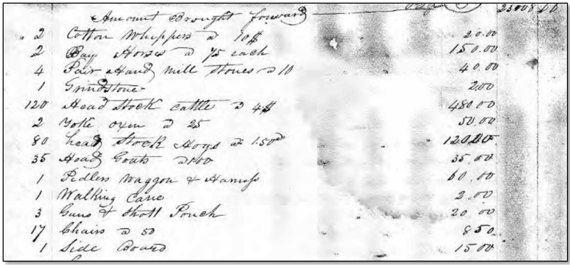

In addition, the inventories give us clues as to the day-to-day workings of the plantation or farm. Timothy Hopkins’ inventory lists 120 head of stock cattle, 2 yoke of oxen, 80 head of stock hogs, and 35 head of goats. He also had 2 cotton whippers, machines that whipped cotton, cleaning out seeds and other parts of the plant that were caught up when it was picked. There are more than 100 axes on the inventory, ranging in value, indicating perhaps that his first group of slaves had to do a lot of clearing of trees on the land. (There are no Hopkins in Camden County, Georgia, appearing in censuses before 1820.)

Other telling items in the inventory were his ownership of 600 pounds of sugar and 70 pounds of tobacco. Worked by 79 slaves during Timothy’s tenure, which ended in 1833, and more than 200 slaves when William died sixteen years later in 1849, this was no small-scale operation.

The distribution of the land between the widow and William’s two heirs characterizes much of the land as swampland, and provides some clues as to its location as well.

Finding Your Ancestors in Probate Records

- Start by searching for estates of individuals in the area where your ancestors were living in 1870, the first time all black people were listed by first and last names in a federal census. Search for the names of individuals who share the same surname that your ancestor was using in 1870. Look closely at all of the records. You may need patiently to browse through some records in the collection, since not all of the records in the collection are indexed. See this guide for tips on using the collection on Ancestry.

- If you’re not having luck finding your ancestor in the probates of those slaveowners who share your ancestor’s surname, expand your search to others who lived in the area where you have found your ancestors living in the 1870 census. A look at the 1860 census slave schedules can give you a very reliable idea of the names of the slaveholders who were living in this area just a decade earlier.

Beyond the names of your enslaved ancestors and their family groupings, records can contain a most fascinating history of the actual place where your ancestors once lived, toiled, fell in love, married, and had children. Their story–the story of our black enslaved ancestors–is one worth seeking and preserving not only for your family and your descendants, but for us all, as part of the great saga of the history of the American people. Good luck with your search, and please write to me as you progress!

Do you have a mystery in your own family tree? Or have you wondered what family history discoveries you could make with a DNA test? Send Henry Louis Gates, Jr. and his team of Ancestry experts your question at ask@ancestry.com.

— This feed and its contents are the property of The Huffington Post, and use is subject to our terms. It may be used for personal consumption, but may not be distributed on a website.

Read the article:

Finding a Name: Why Probate Records Are a Gold Mine for African Americans