[ad_1]

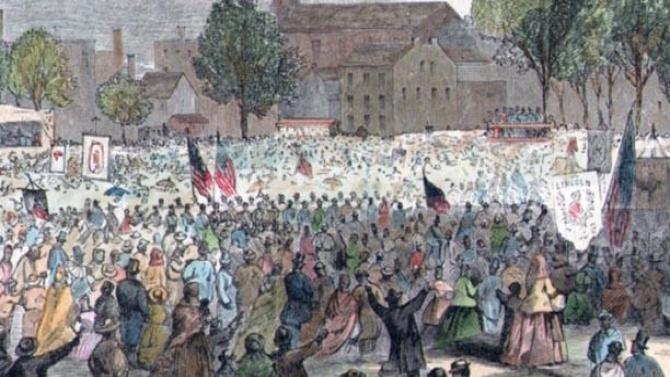

A depiction of Emancipation Day celebrations in Washington D.C.

Wikimedia Commons

Emancipation Day, a holiday marking the anniversary of an act of Congress that provided for the emancipation of people held as slaves in the District of Columbia, will be observed Friday, April 15, this year (since April 16, the actual anniversary date, falls on a Saturday). It was on April 16 in 1862 that President Abraham Lincoln signed legislation that abolished slavery in the capital city of the United States. It was an important day in the history of American liberty.

And it was largely due to an unlikely figure, a former shoemaker from Massachusetts. And yes, history buffs, the Civil War had been in progress for a year, meaning that slavery was still legal in the capital of the Union while it was fighting a war in which slavery was a key issue.

In May 1836, Henry Wilson, a young shoemaker from Massachusetts, was visiting the city of Washington, D.C., and took a walk to the section of the city where several slave pens were located. Seeing Williams Slave Pen (where almost five years later, a kidnapped free black man named Solomon Northup was confined), he was horrified by the conditions in which the enslaved were housed. He heard their moans and was haunted enough by them that when he returned home, he soon joined the anti-slavery movement. As time went on he entered politics, and was eventually elected a United States senator.

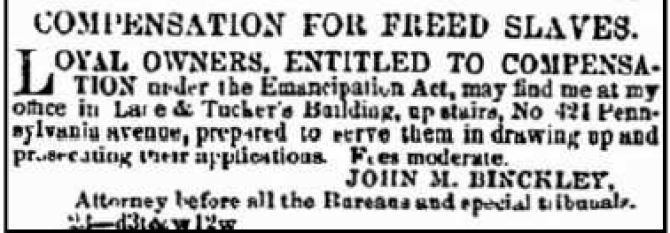

Though previous efforts had been made to eliminate slavery in the District of Columbia, it was a bill introduced by Sen. Wilson late in 1861 that finally became a law. The measure, titled “An Act for the Release of Certain Persons Held to Service or Labor in the District of Columbia,” not only emancipated the slaves but also provided for compensation to owners of the slaves being freed.

Newspaper advertisement offering slave owners compensation for emancipated slaves

Library of Congress Chronicling America Collection

The bill was debated in the Senate over the course of several days. Noah Brooks, in an 1895 book titled Washington in Lincoln’s Time, recounts that “a great many decent-looking and intelligent-appearing colored men thronged to the Senate to hear what the speakers had to say.” The Senate passed it by a vote of 29-6.

The House of Representatives considered the bill in April, and it also passed there, 92 voting in favor and 38 against.

Having passed both houses of Congress, the bill was sent to President Lincoln. Although some pro-slavery advocates predicted that he would veto it (Lincoln did express some concerns that the bill’s progress was too hasty, and also had thoughts relating to how the compensation amounts would be determined), Lincoln signed the bill into law April 16, 1862.

Many slave owners had anticipated this. During the days preceding Lincoln’s approval of the bill, many slaves–-particularly those who would fetch the best prices at slave markets-–were taken out of the District. Either owners did not want to give up their slaves, or they felt that their monetary value was higher than what they would receive as compensation under the new law.

The National Republican newspaper hoped that Lincoln would speedily sign the legislation because “every hour [of delay] commits an additional fellow being to slavery.”

One writer witnessed, at 6 a.m. on the day Lincoln signed the measure, a wagonload of enslaved, mostly women, being led out of the city by a white man. “The wailing of the women will not soon be forgotten by those who heard it,” he wrote.

[ad_2]