Contrary to what you may have heard — or thought for yourself, after waking up from that re-occurring nightmare where your life is destroyed by a smartphone app — “Black Mirror” is not anti-technology. It has been likened to the “The Twilight Zone,” often by creator and writer Charlie Brooker himself, and in that comparison the use of gadgetry on Britain’s Channel 4 anthology is most clear. Where Rod Serling worked with supernatural objects and plot devices, Brooker uses current technology “cranked up 5 percent” as his magic. That sweaty fear you feel while watching, say, the post-credits scene for the…

Contrary to what you may have heard — or thought for yourself, after waking up from that re-occurring nightmare where your life is destroyed by a smartphone app — “Black Mirror” is not anti-technology. It has been likened to the “The Twilight Zone,” often by creator and writer Charlie Brooker himself, and in that comparison the use of gadgetry on Britain’s Channel 4 anthology is most clear. Where Rod Serling worked with supernatural objects and plot devices, Brooker uses current technology “cranked up 5 percent” as his magic.

That sweaty fear you feel while watching, say, the post-credits scene for the episode entitled “White Bear,” is exactly what Brooker intended. “I want to actively unsettle people,” he told HuffPost in a recent interview, while walking the streets of London and trying to hail a cab.

“Just generally, that’s not my life mission statement, do you know what I mean? I’ve done other shows, comedy shows, that sort of thing, where the goal primarily is laughter. So, unsettling people isn’t my raison d’être.” And, as would happen repeatedly throughout the conversation, Brooker said that last bit with a mix of drama and concealed giggling, clearly just as amused by his own sardonic playfulness as you might be on the other end of the line.

|

He gathered himself, and grew serious again, his tone almost a warning he’d put all kidding aside. “It’s more that I felt a lot of drama exists to kind of reassure people,” he said. Certainly, reassurance is not the point of “Black Mirror.” Like “The Twilight Zone” before it, Brooker’s show hacks into anxieties and exacerbates them where other series seek to assuage.

“Even with crime drama, usually the bad guy is caught,” he said. “There are a lot of series where shocking events happen, but they’re not usually tethered to the real world. They’re irrelevant to the real world.”

Enter the macrocosm of “Black Mirror”: “Of course, everything happens in the same universe, because we’re in one!” Brooker sneered, when asked. None of the episodes depict the same world, though.

As fan theories would have it, all of the installments can be connected. That idea does not confuse Brooker. In fact, he planted it in the fabric of the show.

|

You might have noticed the ties to every previous episode in the Christmas Special (“White Christmas,” starring Jon Hamm), like the ticker tape harkening back to the prime minister of “The National Anthem,” or Irma Thomas’ song, utilized in “15 Million Merits.” Those Easter eggs were deliberate on Brooker’s part, but it doesn’t mean any conclusions can be drawn regarding worlds, or universes, or what have you.

Asked if he was teasing us, the desperate audience, panting over his every reference, Brooker is thrilled: “Oh, I am!” he said, pausing to appreciate the acknowledgement of his handiwork. “Really, I thought it was fun. It’s sort of just a treat for people who are paying attention.”

Most of the episodes can be described as taking place in a part-satirical, part-allegorical, near-distant future. The clearest departure from that mode is “15 Million Merits,” which Brooker noted was one of the more challenging episodes to execute. “That world we created there could really only exist for about an hour,” he said. “It doesn’t really hold water as a real plausible thing. You could never do a do a 22-part series set in that world.”

|

As for the rest of the episodes (seven total, if you count the Christmas special) there are so many similarities to the world we currently inhabit, people often confuse the two.

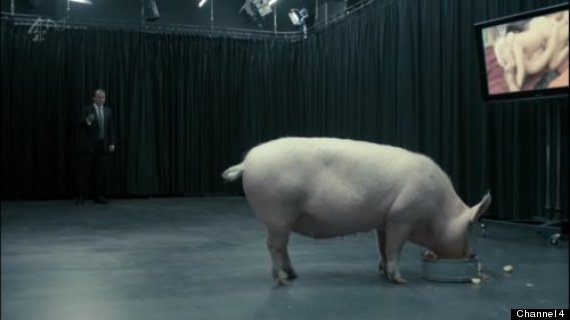

“I’ve seen people criticize ‘National Anthem’ in regard to whether everyone in the country would turn up and watch the prime minister doing that,” Brooker said of the episode, which featured a fictional British prime minister having sex with a pig. “No, they wouldn’t. Of course, they wouldn’t! It’s not a documentary. I’m not saying that people are such dumb monsters that everyone would enjoy it. You know, it’s a satirical fantasy.”

Yet, there are such close parallels to our own world, the satirical fantasy part is often lost in the audience’s fear. That’s no accident. Almost every episode has started off as grounded by present technology.

“It always comes from a what-if idea,” he said, noting the example of “Be Right Back,” in which a woman talks to her deceased partner through an app (which, by the way, exists!). Brooker was up late lurking on Twitter one night, when he thought of the idea of artificial intelligence for the dead.

“I was seeing all these updates from various people, and I thought, ‘What if these people were dead? How do I know these people aren’t dead? What if all these people had been replaced with a bit of software? How would I know?'” he said feverishly. “That was the starting point for the story. And then really that picked up as I went along.”

|

There are exceptions to that style. Probably the most labored writing process came with “White Bear,” which Brooker rewrote four times. It all started when he was working on “Dead Set” (a zombie show which, he’ll have you know, pre-dated “The Walking Dead”).

In one scene, a character played by Riz Ahmed (now of “Nightcrawler” fame) was being chased by a zombie. Local school kids gathered around the set and starting shooting videos and taking photos on their phones. “I thought, ‘That’s actually an interesting and frightening image,'” Brooker said, “because they’re standing there, not intervening.”

He decided to write about it for the next season of “Dead Set,” using the idea that a photo spread over social media had unlocked this primal urge for people to be voyeurs of agony. He got the green light, but there were budget issues or, as he put it, “We couldn’t destroy all of London.”

The team looked for a location at the nearby Royal Air Force base, and found a housing development where pilots lived with their families. As Brooker was being shown around, the guide pointed out a gas station and auditorium, before noting the fences around the compound would need to be edited out of the shot. That’s when it came to him.

“Suddenly, like a pen had dropped, I thought, ‘Hang on! What if this is not really happening. What if somebody thinks this is happening and it’s not really happening?’ And then, suddenly, everything locked into place.” he said. “That made it 1000 times better. And I got very excited, indeed. I wrote that, it was like a fever dream writing that script up to that point.”

|

With this idea, like many others, Brooker explains his thoughts as though they are obvious things he stumbled upon. He finds himself quite funny at times, though seems oblivious to the true brilliance of these concepts.

“White Bear,” most directly, is blatant commentary on society rather than technology (if only because our iPhones could easily power that nightmare — no “cranking up to 5 percent” required). In many ways, that makes it a sort of quintessential episode of “Black Mirror.” Ultimately, technology is not the reason to be scared.

“We’re not saying all technology is bad,” he emphasized. “We’re just going, ‘Hey, wouldn’t it be creepy if this happened.'”

By that formula, though, technology often informs the storytelling process. “We discuss it all very early on, and often the script will alter on design,” Brooker said. He has always been adamant that the devices on the show seem like they would work and exist in the real world.

With a background as a video game reviewer (among “many” other things), Brooker has a special appreciation for tech. He’s gone out of his way to hire a design and special effects team who are thrilled to go the extra mile once the story is in place. You’ll note little details — like the protagonist’s touch-screen easel in “Be Right Back” — that really take things to the next level.

Since technology is so often executed in such a disturbing way on “Black Mirror,” it’s strange to hear the joy in Brooker’s voice when he discusses creating it.

“The design team had a field day with that easel,” he said. “They were like, ‘Let’s create something we love!’ With the technology, we have tendency to sort of fetishize that. They were also, when they were working on the design for that, like, ‘Oh, we should copyright this. It’d be brilliant if this existed.'”

|

In that sentence lies a wholly frightening thought, inextricably linked to watching the show: Just as Brooker follows what-if ideas to create these scenarios and the tech they require, the audience must also ask themselves, “What if any of this were to happen?”

“Oh, God, all of the episodes terrify me to some respect,” he exclaimed, when asked which he found most upsetting. “In particular, ‘White Bear.’ We bottled a nightmare there.” That episode combines elements of “The Truman Show” with criminal justice. “That’s truly frightening,” Brooker said, “because it ultimately pulls out to reveal an insane society.”

Seasons 1 and 2 of “Black Mirror” are currently available on Netflix.

Original post: