[ad_1]

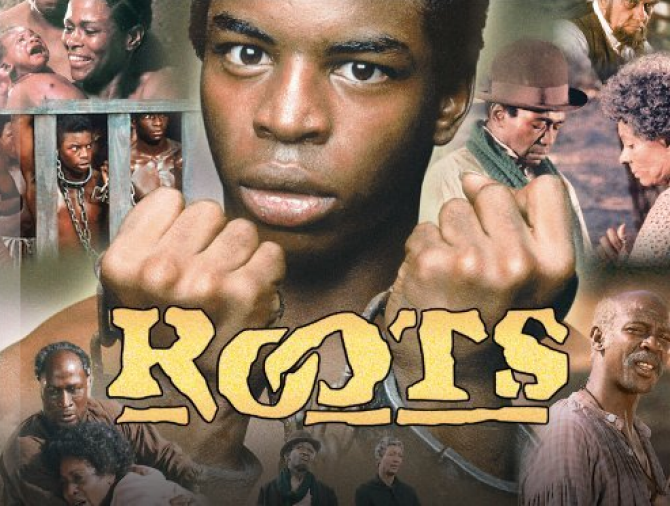

Montage of scenes from the 1977 miniseries Roots

IMDB

Kunta Kinte now joins USS Enterprise Capt. James Tiberius Kirk and Sherlock Holmes in the growing worldwide popular-culture club of the 21st-century reboot. I was shocked to learn that Roots is being remade and will be broadcast Memorial Day on three different networks: History, Lifetime and A&E.

A Roots redux astounds me, because the original Roots television miniseries, a loose adaptation of a loose adaptation of African and African-American history, was a seminal event, not so much made by Hollywood filmmakers but sprouted out from the collective American soil and nourished by the rain of enslaved African blood. Roots, the story of one family’s journey from chattel slavery to a segregated freedom, stirred and revealed the collective unconsciousness of a people. Ogun and Shango even created a major snowstorm to force the East Coast inside all week to watch it on ABC when it dominated nightly prime time in January 1977.

The book’s author, a black freelance writer for Playboy and Reader’s Digest and retired U.S. Coast Guard public relations representative named Alex Haley, had created quite a follow-up from his previous, and first, book, The Autobiography of Malcolm X as Told to Alex Haley. He claimed that, almost miraculously, he had found a way to follow his ancestry all the way back to Africa, reattaching the cords of family and heritage that the whites who worked the African slave trade had purposely and comprehensively cut. Roots documents the journey of Haley’s family from West Africa to Tennessee. Haley’s two books became the most important ones in late-20th-century black American homes, other than the Bible and the Quran.

I was 9 years old when Roots premiered on ABC, and I remember shuddering with rage when the enslaved African Muslim Kunta Kinte—played by the then-unknown actor LeVar Burton, not yet engineering starships or reading books aloud—was whipped into his American and Christian name, Toby Waller. To know that was true! That it really happened!

Decades later, I returned to another part of the story in the 1990s as a struggling adult freelancer. I memorized Haley’s professional life as he told it in his collected Playboy magazine interviews, and began watching the last episode of Roots: The Next Generations, the successor miniseries, over and over again.

In that episode, Haley, played powerfully by James Earl Jones, discovers and follows a historical and genealogical trail that leads not only to his lost African surname Kinte and his Mandinka heritage but also to his exact ancestral village in the Gambia! If he can be a successful freelance magazine and book writer, I fantasized, so can I. A little candle of faith flickered inside me, because the episode showed that Haley had trusted in himself and his mission. His massive success proved the power of belief.

So I felt real pain when I found out that Haley was, in the words of the Village Voice, a liar and a fraud. Philip Nobile’s 1993 exposé of Haley, published one year after his death at the age of 70, revealed that he had made up most of the story, with the compliance of white, liberal publishers and a Gambian government hopeful for tourist dollars.

A recent book, Alex Haley: And the Books That Changed a Nation, by Robert J. Norrell—billed by its publisher as the first full biography of Haley—is trying, through scholarship, to rescue his modern reputation. Norrell wants Haley to be seen not as the phony of Nobile’s reporting, or the crass Republican opportunist portrayed by Manning Marable in his controversial biography of Malcolm X, but as a sincere black man dedicated to documenting black history. Haley’s riveting and ultimately triumphant speeches to audiences in the late 1960s and early 1970s about his roots, according to Norrell, served as a perfect white, liberal alternative to the angry black power movement.

The biography’s bottom line: Alex Haley was a black writer who loved a good story and wanted to make money from writing one. After writing Malcolm’s autobiography, he penned a historical novel that, unfortunately, was published, marketed and defended as nonfiction. He and Doubleday decided that if major magazine journalists and authors such as Truman Capote, Tom Wolfe, Hunter S. Thompson and other white writers of the time could get away with mixing facts and lies in their nonfiction because of their works’ literary value, then Haley could, too.

Doubleday accepted what biographer Norrell called “a liberal definition of historical truth,” and the resulting book shook the literary world’s white marble floor. When detractors pulled out historical microscopes, the team doubled down. “The more doubtful his critics were,” writes Norrell, “the more adamant Haley became that Roots was factual.” The winner of a special Pulitzer Prize strove for peace while fighting mostly unfair plagiarism lawsuits and angry ex-wives.

[ad_2]