[ad_1]

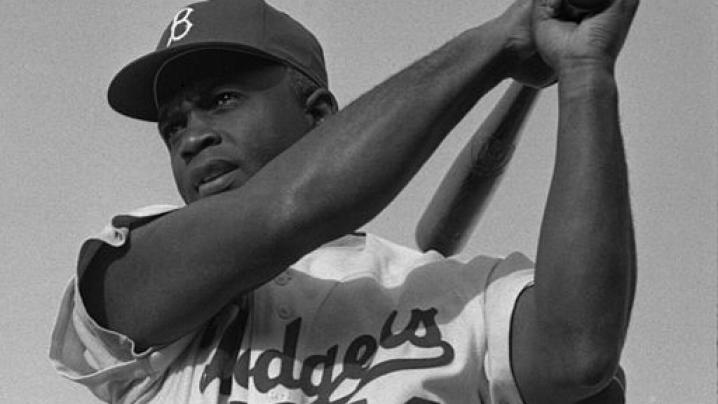

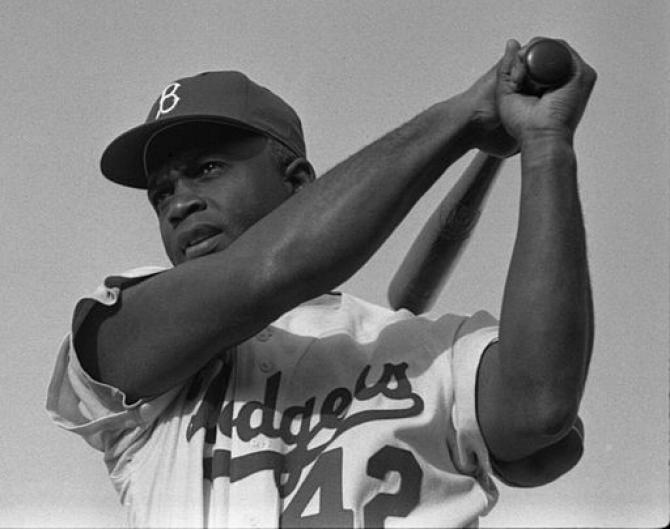

Jackie Robinson in 1954

Bob Sandberg/Wikimedia Commons

With Ken Burns’ two-part Jackie Robinson PBS documentary looming this month, Negro-newspaper sportswriters will return to black America’s consciousness. The Negro press of 1945 to 1948 not only advocated for the desegregation of Major League Baseball but also, for Jackie Robinson’s and the race’s sake, became the de facto public relations wing of his team, the Brooklyn Dodgers, to make sure the “great experiment” succeeded.

Wendell Smith, the Pittsburgh Courier sportswriter and columnist who, along with Sam Lacy of the Baltimore Afro-American and Joe Bostic of the (New York) People’s Voice, had been lobbying hard for desegregated baseball in the mid-1940s, was clear on his responsibilities. By 1947 the battle to get a pioneer Negro baseball player picked was over, but the larger, greater experiment was about to begin. The new goal of both the Negro press and the Brooklyn Dodgers organization: Keep Jack Roosevelt Robinson safe off the field, and help keep Negroes calm in the stands, aisles and parking lots.

The unprecedented white racial backlash that Robinson was going to experience would be vicious and sustained. So Branch Rickey, the president and manager of the Brooklyn Dodgers, knew it was not only Robinson but also the Negro press that had to keep things ice and nice.

Negro newspapers were very important to what would happen next because by the mid-1940s, they had become, with the exception of the black church, the most powerful institution in black America. The Courier, the Afro-American and the Chicago Defender were de facto “national” newspapers, available weekly in any city with a sizable black population. Media scholar Jannette Dates, dean emerita of the School of Communications at Howard University, has written that by 1947, Robinson’s first season as a Brooklyn Dodger, the combined circulation of more than 100 Negro newspapers—led by the Defender, the Courier, the Afro-American and the New York Amsterdam News—“was in excess of two million copies a week.”

At the time Robinson was chosen, the Negro press was just concluding its militant World War II coverage of the U.S. government’s abuses of the Jim Crowed soldier—reporting that white Washington, D.C., considered so harsh that the federal government seriously debated shutting down Negro publications and trying the publishers for sedition—treason. Although it covered segregated institutions like the Negro Leagues thoroughly and lovingly, the mood of the Negro press was one expressing the want of nothing short of full equality. It was a time in which the Defender carried a front-page box score showing how many Negroes had been lynched since last week’s edition.

That radical tone, at least for Major League Baseball, moderated significantly for Robinson’s sake when he was signed to the Montreal Royals, the Dodgers’ farm club, in late 1945. With Robinson officially in the big leagues, the Negro press collectively had to create a collective message and stick to it. It had to do its part to make baseball desegregation work. So the press collectively decided in April 1947, the time of Robinson’s Dodgers debut, that if they could not control how whites responded to Robinson, they could try to control how Negroes responded. The fate of Jackie Robinson rests in the hands of the Negro people, editorialized the nation’s top Negro newspapers. This was because the prevailing fear at the time was that overexcited Negro fans would wind up causing race riots in the stands over Robinson’s performance and treatment.

Robinson was holding down enough. His every move and sentence was now scrutinized by newspapers of both colors.

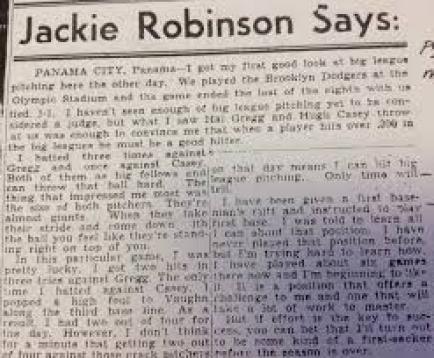

The de facto public relations campaign that the Negro press created for Robinson had another important component: an op-ed column by the new Dodger star himself, documenting his first season. The Courier ran Jackie Robinson Says, ghosted by Smith, exclusively.

Many national black leaders and luminaries had their own press columns. (In the column The People’s Voice in the mid-1940s, singer and film actress Lena Horne, a very serious race woman, shared op-ed space with singer-activist Paul Robeson and scholar-activist W.E.B. Du Bois.) But Robinson’s column had a special purpose: It was to tell Negroes to ignore the virulent racism they saw him quietly endure, and to tell them that he was fine and that they should look only at the positive.

An excerpt from the column Jackie Robinson Says

Hope.edu

An example: On April 22, 1947, the Phillies played the Dodgers at home. Egged on by Phillies manager Ben Chapman, an Alabama native, the Phillies players screamed racial obscenities at Robinson from their guest dugout at Ebbets Field: “We don’t want you here, n–ger! Go back to the bushes! They’re waiting for you in the jungles, black boy!”

Robinson, of course, was upset, but he promised Rickey that he wouldn’t retaliate. So he used the column to tell his readers that he was unfazed by those redneck insults: “The things the Phillies shouted at me from their bench have been shouted at me from other benches and I am not worried about it. They sound just the same in the big league as they did in the minor league.”

His column read like an intimate diary of his thoughts as he made this huge civil rights and sports transition. Readers were able to follow his first-person thoughts as his first season progressed. But the column was really designed to emphasize that Robinson, a man of consummate dignity, met several white people of goodwill on his journey, and that the American spirit of fairness and fair play would not be stopped by what he pretended was a small number of racists. If I can take it, he seemed to say, you can, too.

Robinson would not be the only member of the column-writing duo to obtain legendary status. Wendell Smith later ghostwrote books for boxing legend Joe Louis and another baseball great, Roy Campanella. Robinson always acknowledged not only the role of the Negro press in his career but also the great personal assistance he got from its sportswriters.

In his second, and more honest and angry, autobiography, I Never Had It Made, the then-retired ballplayer and business executive wrote: “In a very real sense, black people helped make the experiment succeed. … I learned … that clergymen and laymen had held meetings in the black community to spread the word. We all knew about the help of the black press. Mr. Rickey and I owed them a great deal.”

[ad_2]