Three words pierced the white noise of Grand Central Station Tuesday night, jolting harried passengers and a fanny-packed tour group from Lancaster County, Pennsylvania. The words, the last spoken by Eric Garner, have become a rallying cry for activists around the country: “I can’t breathe.” This time, the speaker was Chazz Giovanni, a recent graduate of the acting program at SUNY Purchase. Hard to miss in a red puffer coat and Tiffany blue hat, Giovanni recited all of Garner’s last words — an unintentionally chilling monologue captured on video before the black Staten Island man’s death in July after a …

Three words pierced the white noise of Grand Central Station Tuesday night, jolting harried passengers and a fanny-packed tour group from Lancaster County, Pennsylvania. The words, the last spoken by Eric Garner, have become a rallying cry for activists around the country: “I can’t breathe.”

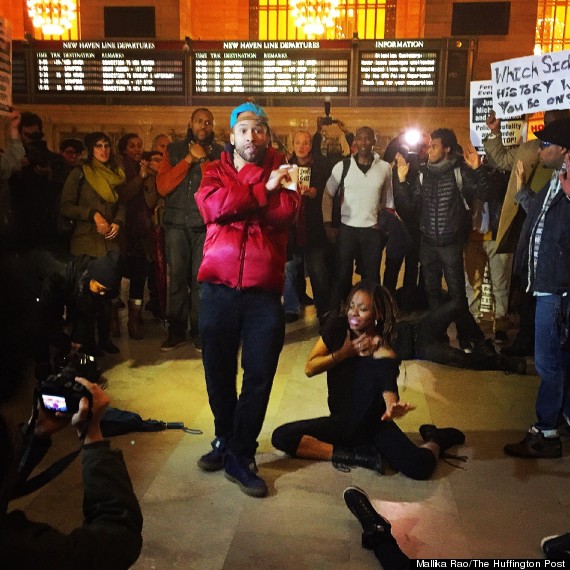

This time, the speaker was Chazz Giovanni, a recent graduate of the acting program at SUNY Purchase. Hard to miss in a red puffer coat and Tiffany blue hat, Giovanni recited all of Garner’s last words — an unintentionally chilling monologue captured on video before the black Staten Island man’s death in July after a white police officer, Daniel Pantaleo, put him into a chokehold.

As Giovanni bellowed the now-familiar lines — Every time you see me, you want to mess with me … Please just leave me alone … It stops today — dozens of dancers circled him, some beating on cookie tins as they chanted, “We can’t breathe.” Others broke into pairs to act out a simple, stylized move based on a chokehold. After each round of Garner’s monologue, the group fell to the ground, miming death.

Led by a group of artists who spread the invitation by word of mouth, the grassroots “die-in” slotted into what organizers are calling a Week of Outrage, a series of nonviolent protests across New York City building to a supersized demonstration this Saturday.

Garner’s plea has taken on its own life. In the days since a grand jury decided not to indict Pantaleo in his death, the words have been displayed on the chests of NBA players and echoed throughout social media. “There was this quote staring me in the face,” Fred Shapiro, editor of the Yale Book of Quotations, recently told The Washington Post, explaining his decision to revise his list of 2014’s most notable quotes to put one of its newest — “I can’t breathe” — at the top.

For many, the phrase represents tensions that have been building for years in communities where run-ins with police are common. “When I think of someone breathing, it’s like someone is at ease,” said Shamirrah Hardin, a high school dance teacher who led the choreography of Tuesday night’s performance. “All is well. Everything’s ok. But we can’t keep on relaxing and breathing when people are getting choked out left and right, and gunned down.”

Protests in New York mirror those rippling out across the country from Ferguson, Missouri, where another grand jury recently decided not to indict Darren Wilson in the shooting of Michael Brown.

Jamel Mims, a multimedia artist and co-organizer of the Week of Outrage, said he believes civil disruption is the most effective way to honor Garner’s memory, by forcing Americans to consider the nuances of police procedure rather than going “back to business as usual — Black Friday shopping, holiday shopping.”

“Business as usual is black boys … getting murdered every 28 hours,” he said, referencing a popular statistic pulled from a 2013 study of online police reports by the Malcolm X Grassroots Movement. “We have to say no more business as usual.”

Statistics on fatalities at the hands of police officers are limited. The country’s police departments self-report records to the FBI, and many don’t file fatal shooting reports in a timely manner. The city of New York — where Garner’s death this year was notably followed by that of Akai Gurley, an unarmed Brooklyn man killed in a stairwell by a cop — hasn’t filed reports since 2007, according to a recent report by ProPublica, the nonprofit investigative journalism unit.

The data that is available shows a dramatic racial imbalance when it comes to young men who are killed during police encounters. In the same assessment, ProPublica analyzed the FBI’s Supplementary Homicide Report. Per that report, young black men — ranging from 15 and 19 years old — were killed by police at a far higher rate between 2010 and 2012 than white men of the same age: 31.17 per million black males in that age range, versus 1.47 per million for whites.

It’s hardly a new notion that black men, whether guilty of a crime or not, face greater suspicion from law enforcement officials than their white peers. Mims said that he was assaulted by a policeman while in Boston one summer and then unlawfully arrested. He had just won a grant from the prestigious Fulbright Scholar Program to study hip-hop in Beijing.

Though he eventually was able to clear his name with the Fulbright committee, he said his status was initially “threatened” when the committee found out about the arrest. It was a harsh wake-up call, he said, an “aha moment that it doesn’t really matter what you get” in life — scholarship or not, guilty or not — his future could change with the click of a handcuff.

Giovanni, who is half-black, said he had his own unbelievable moment when he was only 11 years old. He was on his way home from a movie with his friends when two cops responding to a call accused him of snatching a woman’s purse and throwing it into a nearby lot, he said. Though their search turned up nothing, he remembers police letting him go with these words: “At least you can tell your friends you were stopped.”

Giovanni said he wonders whether black men still even feel motivated to share stories of wrongful arrests or random questioning when the practice is so common. People are “so jaded” by the experiences, he said.

Contrast that with his impassioned shouting Tuesday to the rafters of Grand Central. “I still have my life,” he said. “I’d rather tell the stories of people who don’t.”

See more here:

Protesters Turn Eric Garner’s Haunting Last Words Into Performance Art