Part 1: The great Army swap

Germantown Hardware sits on Germantown Avenue between Ontario and Venango streets in the middle of a North Philadelphia ghetto. Back in the day, the owner hired a handsome 15-year-old boy with a smile bright enough to illuminate the whole town. His name was Ronald Anderson.

Ronald would stock shelves, sweep and mop floors and load customers’ cars. The job was a lifeline in a poor Black community. But Ronald didn’t like to commit to a regular schedule. He had school, which included being a member of the gymnastics squad. At home, he worked on car motors with his dad. And he was popular with the girls. Some days, Ronald just didn’t want to go to work.

So his twin brother Donald would take his shift without the owner even knowing.

“Ronald would go in one day. Donald would go in for him the next day,” recalled Oliver Griffin, a lifelong friend. “[Ronald] might say, ‘Man, they had me moving cement bags over there yesterday. I didn’t get finished.’ So when Donald would go in the next day, he’d say, ‘You want me to finish moving those cement bags?’ ”

I was in North Philly last year asking about the twins because Ronald is the father of Anderson .Paak, the hip-hop recording artist. Anderson .Paak has already won three Grammys and is up for two more this weekend for his 2020 song and video Lockdown, music created in recognition of a year of pandemic and protest.

Since his music went from underground to mainstream nearly six years ago, Anderson .Paak has been constantly asked about his heartache-filled triumph-over-adversity journey.

Andrew Chin/Getty Images

His dad, who died in 2011, wasn’t only an identical twin but a dreamer, a striver, a prankster and an addict. His mom, adopted from a Korean orphanage, is a survivor, a go-getter, a giver and a product of her own insecurities about relationships and what it takes to sustain them.

His mom, dad and stepdad all did long prison sentences. Anderson .Paak got married twice at a relatively young age. He’s been homeless, carless and broke.

And yet, in his music, Anderson .Paak has the rare ability to take the most macabre incident and recount it whimsically without being weighed down by its gravity. Some of it, though, may be too close to the bone even for Anderson .Paak, a mellow, always smiling musician, to discuss. He talks about it, but he holds back some of the details.

Here, for the first time, is the full story.

Brandon Anderson, aka Anderson .Paak, now 35, was 7 the last time he saw his mom and dad together. He is the second-youngest of a blended family with nine siblings. His dad had a good job with the Navy and his mom was one of the only female strawberry brokers in California. Their home had love and material wealth.

But one day the little boy opened the front door to greet his mom and saw his dad nearly strangling her to death.

I’ve tried to reconstruct when I first met Brandon Anderson.

As best I can tell, it was late summer or fall 1993. This was a time when the G-funk, West Coast style of rap was gaining popularity thanks to Dr. Dre’s 1992 album The Chronic and Snoop Dogg’s Doggystyle debut in late 1993. (Years later, Dr. Dre would be instrumental in Anderson .Paak’s success, featuring him on six of the 16 tracks of Dr. Dre’s 2015 comeback album, Compton.)

My family and I had just moved to the suburban sprawl of Ventura County, California, northwest of Los Angeles, where I was working as a reporter for the Los Angeles Times. Brandon’s family was living in an apartment across the street from our townhouse.

My son, Dwayne Jr., ran into Brandon one day while selling candy for a sports fundraiser. Both boys were 7. Brandon was in his yard doing backflips and listening to The Chronic. It was a mostly white neighborhood and the two were surprised to see another boy the same age with the same skin color and the same rap music sensibilities. And each had a 5-year-old sister.

The four kids soon became best friends. I knew the man of their house, Dennis Willingham, as the stepdad. He and I were the only two Black men with young children in the area and we soon developed a friendship. In a county where just 2% of the population was Black, there were certain topics – was O.J. Simpson guilty or not? Was crack brought to Black neighborhoods by the government? – that two Black men could comfortably discuss only with each other.

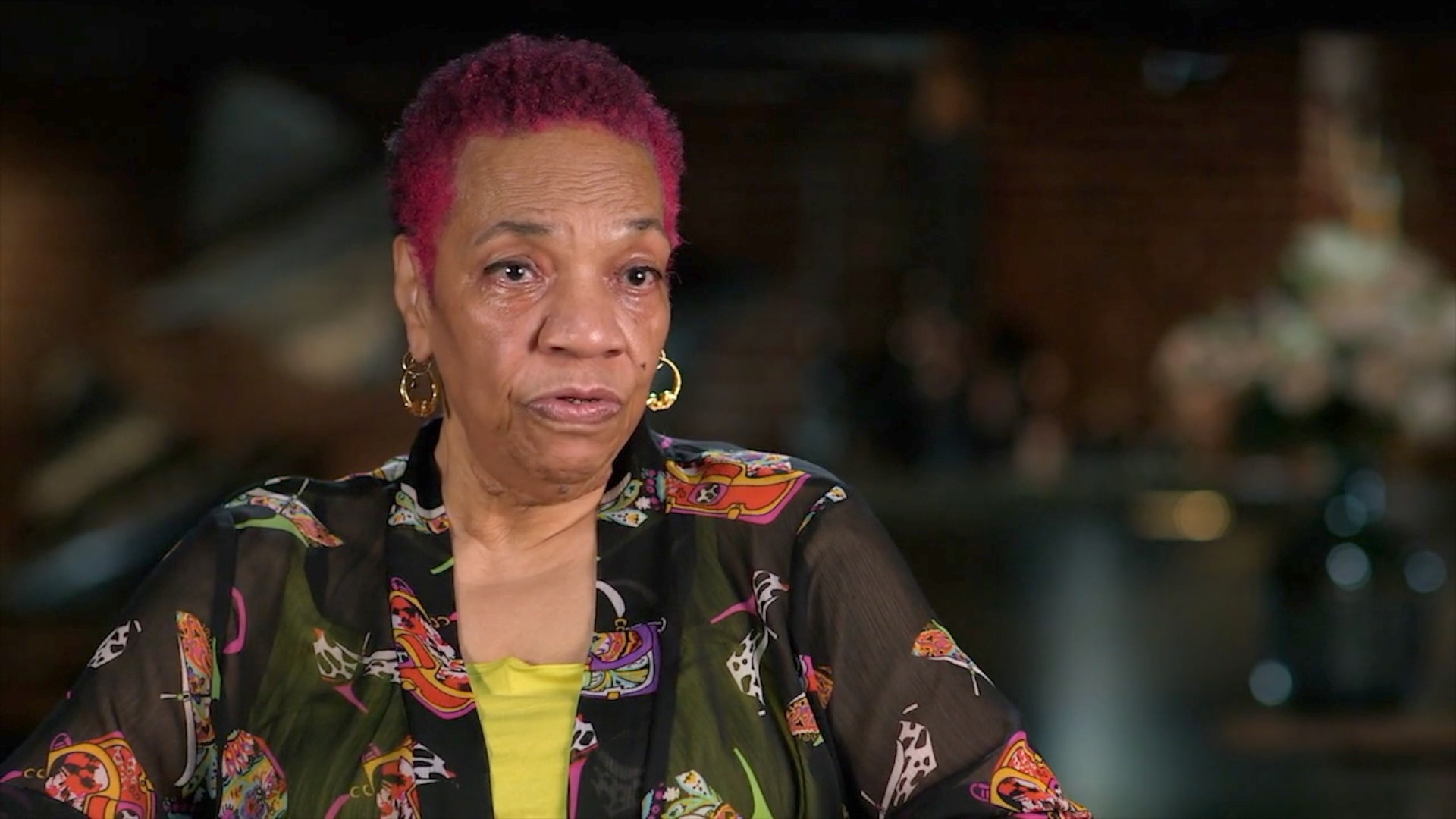

Brenda Paak Bills

In my job covering the courthouse for the paper, I learned about the story of Ronald Anderson, an inmate in the Ventura County Jail, who had been convicted of attempted murder for trying to kill his wife. What I didn’t know back then was that he was the biological father of my kids’ new friends and the estranged husband of their mom, Brenda, my new neighbor.

We lived in Ventura for two years, until August 1995. It would take me another two decades to realize just who my neighbors were – the family of the man I had written about in the newspaper. I finally discovered everyone’s true identity in 2014, when Brandon was performing under the stage name Breezy Lovejoy. Now, I’ve decided to finally write about my relationship with Anderson .Paak and his family – his father, the defendant in my articles, and his mom, stepdad and sister, my neighbors who I came to trust almost as relatives, even if it was only for a couple of years.

Many people have heard him talk about the broad strokes of his life. On Power 105.1’s The Breakfast Club radio show in 2018, DJ Envy, one of the hosts, told .Paak, “This story … is definitely a movie.”

When I heard DJ Envy say that, I thought to myself: You don’t know the half of it.

The story starts in the Tioga section of North Philadelphia.

Ronald Anderson and his twin brother, Donald, were born there on Sept. 22, 1951. Their mom, Marie, who cleaned houses for a living, was a twin herself. Their dad, William, drove a truck delivering ice and also worked as a furniture mover.

The couple had moved to Philly from North Carolina in search of a better life, but ended up finding poverty, despite a lifetime of hard work. Ronald and Donald Anderson had nine other brothers and sisters, with Marie giving birth to five kids before the twins and four after.

With all those kids and a job, Marie ran the household on North 16th Street with an iron fist. Her husband, by contrast, was hands-off and spent his free time indulging in libations and teaching the twins how to fix cars.

In 1965, Marie and William were running errands when she suffered a cerebral hemorrhage and died. The twins were 14. After overcoming their grief, the two boys got jobs shining shoes, bagging groceries and working at Germantown Hardware. It was on these jobs that they began subbing for each other whenever the need arose.

At Simon Gratz High School, they were on the gymnastics squad and spent a lot of time in the auto shop, refining their skills as mechanics. By all accounts, the twins attracted interest from their fair share of girls. One was Barbara Jones, who dated Ronald after seeing him perform as a gymnast. She had to keep her guard up, though, because you never knew what any encounter would be like with Ronald and Donald.

“I would come to [their] house and Donald would always say he was Ronald,” Barbara told me, laughing over the 50-year-old memory. “It was just something about Donald. Donald told me they used to try to switch on girls.”

Their childhood friend Griffin remembers it well. “Donald would start a conversation with a girl. ‘I’ll meet you at 6 o’clock.’ But Ronald would go to the girl’s house at 6 o’clock and pretend he was Donald because Ronald was good talking to women.”

Hannah Price for The Undefeated

Years later, in 1973, Ronald would father a child with Barbara. After Ronald moved to California, Donald would come to visit his new nephew, Darius, and pretend to be Ronald. Ronald had three other kids in Philadelphia, all older than Darius, and Donald would show up at all of their homes and pretend to be his brother.

Barbara said the twins were effective at swapping places because they had the same stocky build, big smile and golden-brown skin. “Their voices were the same. They walked the same. I mean, they were identical, very identical,” she said. “And if one got hurt, the other would feel it.”

The twins’ short legs, compact torsos and powerful shoulders helped them excel in gymnastics at Simon Gratz. They were also street performers.

One block over from their home was Sydenham Street, the hub of activity for the neighborhood. I went there and hung out with four of their old friends – Griffin, Lawrence Randolph, Marvin Palmer and Anthony Byrd, all in their mid- to late 60s now.

“Through the whole neighborhood, they were famous,” Griffin said. “People would pull up and say, ‘Those guys will probably be out there today, doing the somersaults.’ And they would get these mattresses, about six to eight mattresses, and they would do their whole routines out in the street, right here on this corner.”

When the twins were flipping their way into the hearts of the neighborhood in the mid-1960s, Byrd was a hard-hitting linebacker on the Simon Gratz football team. Today, he’s stricken with gout and is not that mobile. As a result, we met in the second-floor bedroom of his Sydenham rowhouse. The walls were painted pink, and a small television played in the background.

I sat at the foot of Byrd’s queen-size bed, next to Palmer, who was sporting an orange beard. He was next to Griffin, and Randolph stood between them. I streamed Dang, a 2016 video featuring Anderson .Paak, the son of their late friend Ronald Anderson, made with Mac Miller.

“Beautiful song,” Byrd said.

When he looks at the video and watches Anderson .Paak singing and smiling as a multiculti group of women come in and out of view, Griffin says, “That’s Ronald frigging Anderson. He likes women of all hues.”

Ronald Anderson, they say, was a sharp dresser and a focused person. He wanted to get out of the ghetto and make something of himself. Donald Anderson, while always ready to help his brother, had no plans of his own. These distinctions would become more evident as the twins grew from teens to men.

As Donald told me when I met him two decades after his teenage years in Philly, “I’m aggressive and a hardhead, and I have a bad temper. That’s why most of our friends would call me the evil twin and he’s the good twin. If you ran into him, he would say, ‘Excuse me.’ If you ran into me, you would have trouble on your hands. I’m not going to let anybody take advantage of me. He didn’t see it that way.”

“Donald wasn’t scared of nothing,” Byrd said, and asked me, “You heard about what they did in the Army?”

Oh, how I’d heard.

The truth is opportunities were limited for the twins, their siblings and all their friends. They were Black, poor, moderately educated. Most families had two parents at home who worked hard, but didn’t see their economic status improve much. People in the neighborhood say the odds were always against them.

The twins wanted out of North Philly and decided to join the military, which was a common option for many young Black people at the time. Ronald enlisted in the Army in the fall of 1968, even though he had just turned 17. His dad signed a letter falsely saying that he was born in 1950 instead of 1951, which would have made him 18 and an adult.

Hannah Price for The Undefeated

Their friend, Randolph, who joined the Navy, says he and Donald planned to go in on the “buddy plan,” but that Donald backed out. Donald’s older sister, Carolyn, says the Navy rejected Donald because he had high blood pressure.

Either way, Ronald left his twin and entered basic training in North Carolina that November. He then went to Virginia for training in aircraft maintenance. He thought he’d be happy away from home, but he missed his brother and their friends.

Ronald got orders to deploy to South Korea. But before leaving for Seoul, he went back to Philadelphia and told Donald he regretted joining the Army. The night before he was supposed to leave, Ronald sat in his bedroom on 16th Street sharing a shorty of chilled Thunderbird wine with his twin. Years later, when I was covering Ronald’s trial, I ran into Donald and he would recount that night for me.

“Here I thought he had an excellent chance to get out of the ghetto,” Donald told me in 1994. “I told him, ‘Well, I want to go. Let me try.’ He thought it was a joke. I didn’t care if I got caught or not. It would have been better than hanging on the street corners.”

Ronald grabbed a broomstick and demonstrated the gun maneuvers Donald would need to know. He taught Donald how to salute and how to distinguish the rank of one officer from another. Ronald may have thought Donald was joking, but he was going to take Donald up on his offer anyway. After all those times switching places at the hardware store or on dates, this was just one more stunt for the Anderson twins.

The next morning, Donald buzz cut his Afro and slipped on Ronald’s Army fatigues. Sitting at the kitchen table, not believing what he was seeing, was their father. William had agreed to help Ronald exaggerate his age so he could enlist. He hadn’t agreed to let Donald impersonate Ronald in the military. “I know what you boys are up to,” William said. “Don’t get caught.”

Meanwhile, a cab was on its way to the house to take an Army mechanic to Philadelphia International Airport for the first leg of a trip that would eventually end in Seoul. Years later, William and I talked about that moment. In his heart, he knew what the twins were doing was dangerous, he said. Yet he felt powerless to stop the charade.

Instead, William called Carolyn, his oldest daughter. She told me that she jumped into her car and headed to the airport, trying to stop Donald from getting on the plane. She couldn’t find him at the airport and phoned their oldest brother, George, a career military man who had served in Vietnam with the Army’s 82nd Airborne Division.

George told his younger sister not to worry too much. “If he doesn’t know what to do, he’ll be OK,” Carolyn said George told her. “They’ll just think he’s a dumb soldier.”

Donald flew to Seattle, where he spent two weeks in orientation. He then went to Japan, and soon afterward, joined the Army’s 55th Aviation and Missile Command along the Han River, eight miles southwest of Seoul. He was 17 years and 9 months old and he was serving with grown men, some in their 40s and 50s.

Word spread around the Tioga neighborhood that the twins had switched places and that Donald, not Ronald, was in South Korea. Palmer, one of the men I had interviewed in Byrd’s bedroom, didn’t know about the Army swap in the spring of 1969.

He recalled spotting one of the twins out on the block. He assumed it was Donald but soon realized it was Ronald.

“Wait a minute,” Palmer told him. “I thought you went to the military.”

“I did,” Ronald told him.

“They let you out early?”

“No,” Ronald said. “Donald went in my place.”

Ronald said that when Donald came home on leave, he’d probably go back for himself.

In 1994, Donald told me that some of the brass liked him so much that they escorted him into clubs for noncommissioned officers. He also played on the company basketball team, he said.

Courtesy Ron Hamilton

“When I got there, I was a helper on the crew,” Donald told me. “When the guy who showed me what to do left, I was in charge.”

Unlike his brother, Donald was a good dancer. In South Korea, he’d go into Seoul and dance so well that some soldiers who had known Ronald from basic training started to question how he had improved his rhythm so much in just a few months. Donald learned to lower his dance moves a notch to be more like Ronald.

In his down time, Donald would write to Ronald in North Philly. Friends told me the letters always said what a great time Donald was having. For instance, Donald could catch a taxi or bus into town and play the slots at the Lucky 7 Club. Their friends said Ronald started to wonder if he’d made a mistake allowing Donald to impersonate him and have all the fun.

I tried to find a soldier who was in South Korea with Donald, but I never did. One man who responded to my online entreaties was Ron Hamilton, who served in South Korea at the same time although he didn’t remember knowing Donald. Still, Hamilton had kept all his yearbooks from that era. I flew to Los Angeles International Airport and drove the hour and a half to his house in Vista, California, which is on the way to San Diego.

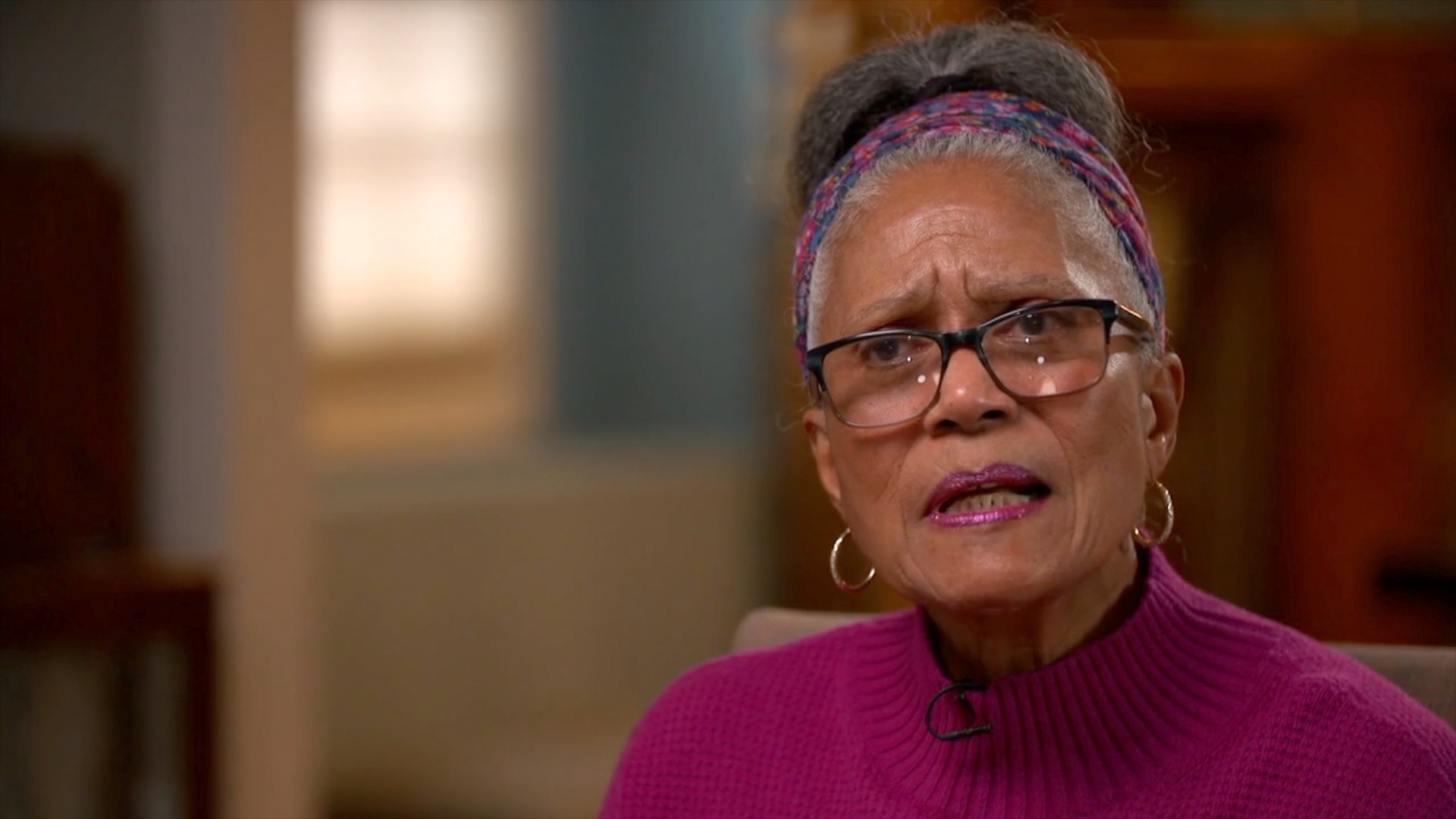

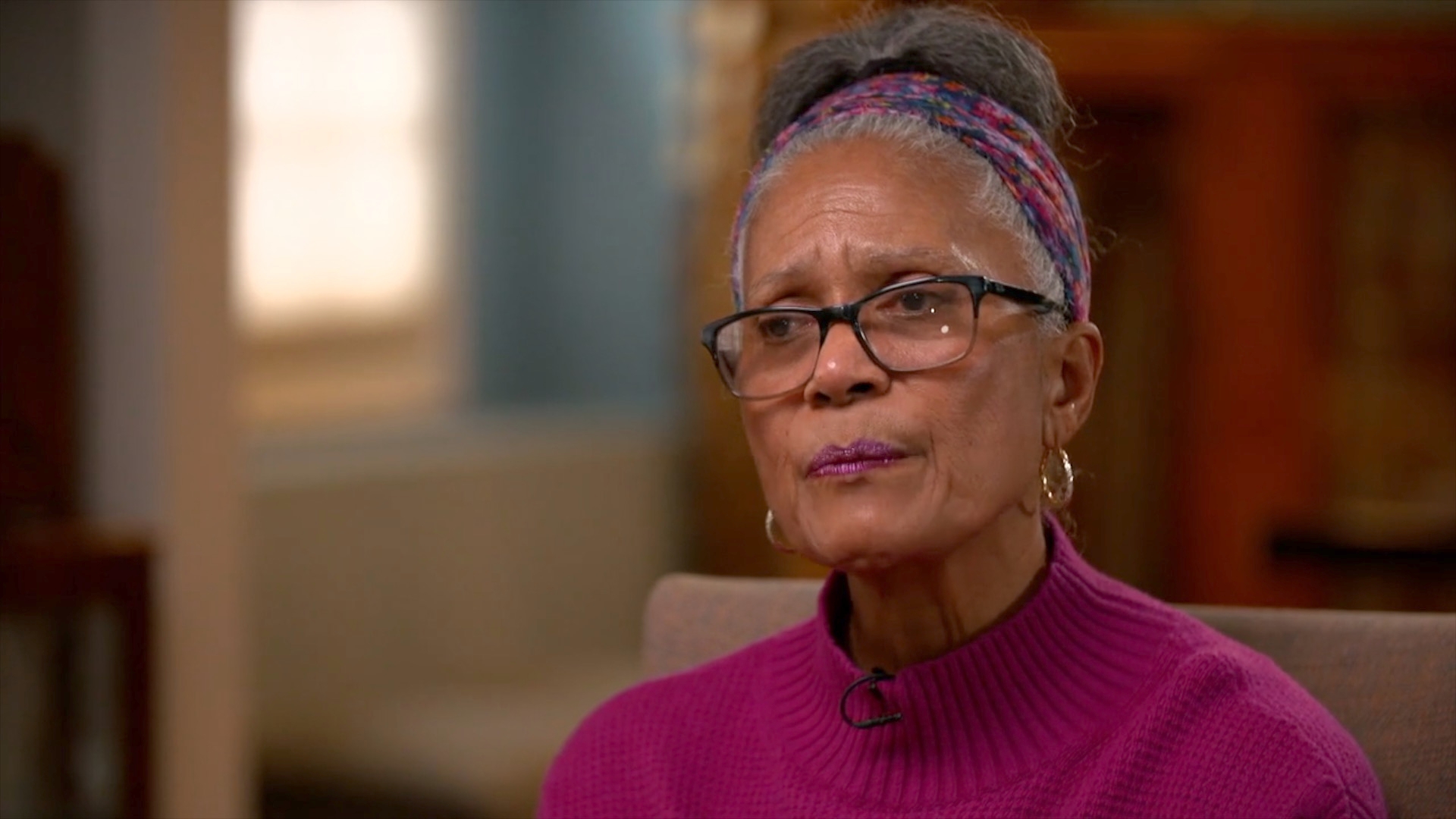

Anderson .Paak’s aunt Carolyn Thomas talks about the Army swap.

Hamilton and I flipped through the yearbooks in his den and found a picture of one of the Anderson twins, although I couldn’t tell which one it was. Whoever he is – Donald or Ronald – the baby-faced twin is standing in front of a wall lined with tools used to repair aircraft. “CHOOSE YOUR WEAPON!” says a caption for the photo. The young man wears a cap and has rolled-up sleeves as he smiles for the camera. In the headshot section of the yearbook, that soldier is listed as Private First-Class Anderson.

I’ve shown those photos to family and friends of the twins, including Brenda, Ronald’s ex-wife and my ex-neighbor. “That’s Donald,” Brenda told me, echoing many others. It’s the closest I’ve gotten to evidentiary proof of the Great Army Swap of 1969.

While Donald was in South Korea, Ronald had to fake being Donald with employers and other authorities back in Philly. He didn’t always do right by his brother. For instance, he didn’t like paying his traffic tickets and piled up so many violations for not paying tolls on the bridges between Philly and South Jersey that authorities issued an arrest warrant for Donald.

Right before Thanksgiving 1969, Donald made his way back to Tioga to a hero’s welcome from his friends. When it was time to return to Seoul, Ronald went back for himself.

After Ronald had left, Donald ended up spending some time in jail because of the unpaid traffic tickets Ronald had accumulated, friends and others said. The local police say they no longer have records related to that arrest or any other brushes with the law the twins may have had, but Donald’s incarceration would mark the first time he’d gone to jail for something Ronald had done.

Darius Jones

In South Korea, Ronald made it through the freezing winter in Quonset huts. By July 1970, Ronald and his brother had served a combined 19 months and he was sent home with an honorable discharge. He was just 18.

Back in Philly, he joined the Army Reserves and, later, the Navy Reserves. By 1974, Ronald had fathered four children – two boys and two girls – with three women and was briefly married to a fourth. In 1975, he joined the active-duty Navy and moved to Lemoore, California, near Fresno.

“We called him Andy,” fellow sailor and friend Curtis Traylor said. “He was a good person but he was mischievous.”

Ronald and Traylor sailed the Pacific and created a singing group called The Pennies, which appeared on a TV talent show called The Gong Show. (Judges hit a gong if an act was especially bad.) The Pennies won their episode and as the show signed off, millions of people could see Ronald standing onstage next to the host, Chuck Barris, holding an oversize check for $ 516.32 (the Screen Actors Guild minimum daily pay) and a trophy.

By the early 1980s, Ronald was working on aircraft at the Point Mugu Naval Air Station in Ventura County. By September 1982, he had another daughter, named September after her birth month. She was his fifth child, none of whom he was providing for.

One night a month after September was born, Ronald, now 31, was out at King Arthur’s, the only nightclub in Oxnard, California, that played Black music. He spotted an attractive woman standing with her friends. Always ready to break the ice and tell a joke, Ronald approached her and identified himself as “Andy.” Her name was Brenda Bills. He asked for a dance.

On the dance floor, Andy bragged about his ability to dance. Brenda laughed because she did not think his dancing was anything special. Andy pointed out a man serving drinks on the other side of the club and said he was a good dancer, too.

Brenda started wondering where he was headed with this conversation when he got to the point.

“That’s my twin brother.”

Brenda couldn’t see the resemblance in the club, which wasn’t well lit. She also figured Andy might have had too much to drink. But she wasn’t going to hold it against him. Before going back to her girlfriends, she gave Andy her phone number.

Tomorrow, “Part 2: A descent into addiction.” Or binge-read the whole story today! 👇🏾

Part 2: A father’s descent into addiction

Now in his 30s, Ronald Anderson had had enough of the playboy lifestyle. He was telling family and friends that he was a changed man.

“He said it was love at first sight,” his sister, Carolyn Thomas, recalled.

Ronald had five kids with four women and had done little for those children. Four of them lived thousands of miles away in Philadelphia. Now, his newest girlfriend, Brenda Bills, was pregnant. But this time Ronald said he was going to create a family.

Brenda Paak Bills

“This would be his first time actually having a hand in raising one of his children,” said Brenda, “because prior to that, it was all the mother and he just wasn’t around.” If she had any concerns about Ronald’s plans, they were dispelled after she told him she was pregnant.

“He was all, ‘Oh, no, we’re going to get married,’ ” she remembered.

Get married they did, in June 1985. Seven months later, on Feb. 8, 1986, Brandon Paak Anderson, the boy who would grow up to become Grammy-winning recording artist Anderson .Paak, was born. Brenda had two daughters, Roni and Camille, from a previous marriage, so the family now had three kids. When Brenda went back to work, her hours were ungodly, and Ronald became the family’s key caretaker.

But would Ronald last as Mr. Mom?

An aircraft mechanic at a Navy base near Oxnard, Ronald would pick his stepdaughters up from school, loudly blowing his horn, getting the attention of all of their classmates. “Everybody,” recalled Roni, the oldest of the two girls, “was pointing at the car.”

He would cook dinner and make sure the girls bathed before Brenda made it home from her day as a produce broker. The girls hung out with him in the family’s yard as he washed his ride. The girls called him “Dad” and helped him take care of their baby brother.

“He was fun, outgoing, smiling, dancing, always playing music,” said Roni, now 44.

“When I started working many hours, he was always there,” Brenda, now 69, said of the first three years of her marriage to Ronald. “Whatever he could do to help lessen my load when I got home, he did it.”

Brenda had met Ronald at a nightclub in the fall of 1982, soon after divorcing her first husband. A little less than three years later, she and Ronald were married in a small wedding attended by family and friends. It took place one week before the bride’s 34th birthday and three months before the groom turned 34.

The couple bought a 5-year-old tract home on Stern Lane in a middle-class part of Oxnard. The streets were lined with palm trees and a vast park with playgrounds, a running track and plenty of grass sat across from the Anderson’s front yard. Roni and Camille had plenty of other children to play with.

At Brenda’s urging, Ronald tried to make amends to his four kids in Philly. He drove there and brought all of them together for the first time. Once the kids in Philly met, Ronald and Brenda flew them to California.

Hannah Price for The Undefeated

It was the first of many extended visits for the Philly branch of the family. At the time, Ronald Jr., the oldest, was 16; Delvia, who everyone called Dee-Dee, was 15; Sherry, 13; and Darius, 12. Roni was 9 and Camille was 6. Ronald Jr. and Sherry would eventually move to California. September, who was born in 1982 in California, the month before Ronald and Brenda met, also spent a lot of time in Oxnard with her father’s family. Brandon was the baby of the group.

I met Darius for dinner in Philadelphia last January and he fondly recalled those days. “When my dad got with my mom, it changed him,” said Darius, who calls Brenda “Mom.” “Before he met her, he wouldn’t have gotten everybody together. None of us knew we had other brothers and sisters. Nobody knew what was going on in his life.”

Dee-Dee agrees.

“We started immediately going and spending our time in California. Summers. Christmas. Blending families,” said Dee-Dee, who also refers to Brenda as “Mom.” “At the time, my mom had two children and he had five. And we never felt the separation. Never heard my mom say ‘my stepkids.’ She says ‘my kids.’ We never said my stepbrother or stepsister. We always said, ‘This is my sister. This is my brother.’ ”

Dee-Dee has always loved her dad hard. She didn’t blame him for being neglectful. She was so pleased when he married Brenda because, she says, he was in love and at his happiest. “My dad was always singing to her,” Dee-Dee told me over lunch in Philly one day. “I never could say I saw my dad and my mom arguing. They had disagreements but never any type of bad arguments, things that kids can see and can sense.”

A lot of family bonding time revolved around food, as both Ronald and Brenda enjoyed cooking. They’d also take the family out to dinner a lot and, at the end of meals, Ronald was known for taking leftover food from everyone’s plates, mixing it in a cup and drinking the concoction, sending the whole family into riotous laughter no matter how many times he did it. Brenda arranged family trips to Vegas and took the kids to Disneyland, Knott’s Berry Farm and Universal Studios.

“He was the supermom and dad,” said Dee-Dee. “My mom could be at the [produce] farm all day and she still would come home and make dinner or we would go out to dinner. We always did family things together.”

The older kids, especially Brandon’s sisters, competed to hold their bouncy, smiling infant brother. Yet he seemed to cry more than normal.

“I just thought he was spoiled because we couldn’t put him down – he was so fat and cute and his cheeks were so chubby,” Brenda said. “But he would cry all through the night. I was like, ‘Oh, my goodness! I’ve never had this problem before, staying up all night holding a baby.’

On top of that, Brenda was pregnant again, expecting a second child with Ronald – the ninth kid in the family overall.

Brenda Bills

A doctor soon diagnosed Brandon’s medical issue. He had a problem with his eardrum, a condition surgeons corrected when he was 2. At the same time, though, Brenda was noticing things didn’t seem right with Ronald. He seemed to be slipping back to his old, selfish ways.

According to numerous interviews over the past year with Brenda, six of the children, family friends and acquaintances, and authorities, here’s what started to occur:

By the time their daughter, Fielding, was born in July 1988, Brenda couldn’t count on Ronald to take care of the children. He was louder and sillier than usual. He’d come home late at night, drunk or stoned, and try to wake everyone up.

And he was always pestering Brenda for cash. Brenda suspected he might be snorting powder cocaine. But it was worse than that. He was smoking crack, a highly addictive form of cocaine.

“People would tell my mom that they saw my dad over in La Colonia, the seedy part of La Colonia, buying drugs when he was in his Mercedes,” Dee-Dee told me, referring to a part of Oxnard that’s long been a drug hotspot.

Sherry, 16 at the time, told Brenda she wanted to go back to Philly to be with her sick great-grandmother. She also told Brenda that when Ronald came home high, he’d come to her bedroom and ask her inappropriate questions about her body. He didn’t touch her but Sherry feared it could come to that.

Brenda confronted Ronald with what Sherry said. He told her he was addicted to cocaine and it made him do crazy things. Brenda checked him into a drug rehabilitation center and Sherry returned to Philly.

By 1991, Brenda’s business partner, Charles Davis, told her he was leaving their business, Saticoy Fruit Co., to her. Davis was an Oxnard icon. He’d grown up there and was a high school football star, earning a college scholarship and briefly appearing on the training camp roster of the San Francisco 49ers. Using his connections from football, Davis started the business and brought Brenda on as an employee around 1980 and as a partner in 1982.

Davis’ decision caught Brenda by surprise. Farming could be a sexist industry and he was the one who had the relationships with the growers who supplied the strawberries. She worried they might not treat a woman fairly. “Oh, God,” she said when Davis told her he was out. “This thing is going to fall apart.”

Not only didn’t it fall apart, the business grew. Brenda got contracts with 45 Carrows and Coco’s restaurants. She bought trucks. She started employing drivers, including the husband of Ronald’s sister, Carolyn. She had the older kids helping out. It was a family affair.

But despite Brenda’s business success, Brandon and his siblings were growing up in the home of an addict. In the middle of the night, Brenda would wake up to loud noises and talking. Ronald would have strangers over, smoking crack. His brother Donald would be in the mix.

From 1988 to 1992, Brenda placed Ronald in treatment for chemical dependency multiple times, but he wasn’t ready and nothing came of it. In one instance in 1991, he walked out of a residential treatment program just hours after she had enrolled him. She found out when a friend called her:

“I just saw Andy walking down the street with his butt hangin’ out,” the friend said, using Ronald’s Navy nickname. “He had a hospital gown on and was barefoot.”

Brenda dialed the manager of the rehab facility to ask how he got out.

ABC NEWS

“Ma’am, we’re sorry but we can’t keep him if he doesn’t want to stay here,” he told her.

“Please,” Brenda pleaded. “If I find him, can you please make him stay? I’m sure you could just make him stay, and if he stayed long enough, it’ll get to him and he’ll go through with this rehab.”

“OK,” the manager said. “I’ll make him stay just one night. After that, it’s gonna be on him. If he decides he wants to leave the next day, I cannot – and you cannot – bring him back here.”

Brenda grabbed her purse, jumped into her Volvo, drove to Ronald’s favorite crack house and banged on the door.

“You better let me in!” she hollered. “Get him out of there or I’m gonna call the police!”

The door flew open and Ronald, still in the hospital gown and shoeless, came flying out involuntarily.

“Get out of here, man,” the house’s owner said as he pushed Ronald out the door, according to Brenda. “She’s crazier than you.”

“Just get in the car,” she said. “We’re going back to rehab.”

“I don’t want to go back,” he told her.

“If you don’t go back tonight, you’re never coming back home.”

Ronald returned to rehab and lasted the full 21 days. For nearly a year after his 1991 treatment, Ronald stayed clean. But the caring father the kids once knew never really returned to the house on Stern Lane. By the time Brandon was turning 7 in February 1993, Ronald had lost his Navy job and was back on drugs.

Brenda kicked him out of the house and set him up in his own apartment which quickly became a crack den. He let his hygiene go and lost weight.

Brenda still gave him money. But that didn’t stop Ronald from getting into the house and stealing tens of thousands of dollars Brenda had been saving to fund the next strawberry season for her business.

She turned for help to an old friend of Ronald’s, a fellow Navy vet named Dennis Willingham. Willingham, who had been injured on a construction job and received a worker’s compensation settlement, said he gave her $ 20,000 to help her get back in business.

Ronald would come by his old home and he noticed that Willingham was there more often. It ticked him off. Willingham, who was 6-feet-1, 275 pounds, said his physical presence made some people in the mostly white county see him as “the Suge Knight of Ventura County.” Willingham would go over and talk to Ronald. According to Willingham, Ronald told him he was going to kill Brenda.

Willingham said he told Ronald if he did that, he’d go to prison and Brandon and Fielding wouldn’t have parents.

“I’m going to kill them, too,” Willingham said Ronald told him.

Not long after that, employees from a local mortuary showed up at the family’s home and said they had been sent to collect Brenda’s body. That was too much for Brenda.

It was April 2, 1993. She dropped all four kids off at a Chuck E. Cheese restaurant and told 16-year-old Roni and 14-year-old Camille to look after Brandon, 7, and Fielding, 4, until she returned. She was going to talk to Ronald.

When Brenda showed up at Ronald’s apartment, he was seething.

Ronald pulled her inside and bolted the apartment door. He pushed her into his bedroom and locked that door, too. He brandished a butcher knife with a 12-inch blade and swung it in her direction.

“If you don’t help me get off drugs and help us with this marriage, then I’m going to kill you,” Ronald said, according to a statement she later gave police. “No one is going to raise my children.”

Brenda Paak Bills

Ronald threw his knife down and slammed Brenda to the bed. He began choking her and she blacked out. When she awoke, Ronald was eye to eye with her.

“If you don’t help me get off the drugs, that’s your fault,” he said.

Brenda convinced him that they should get the children, which they did together. She dropped Ronald back at his apartment, drove home and called the police. Ronald was convicted of spousal abuse and sentenced to six months in jail.

Brenda decided it was best for Roni and Camille to spend time with their father in Texas. She hired a babysitter to look after her two younger children while she worked. For a while, it felt like life might be normal again.

Then came the afternoon of July 19. Brenda arrived home from work around 5:15 p.m. and got out of her Volvo to get the mail. A man ran from behind a gate in the driveway and headed for her.

According to police reports, court records and interviews with family and friends, here’s what happened next:

Ronald, who was supposed to be in jail, tried snatching her purse, but she wouldn’t let go. He threw her to the street, face first, and choked her until he cut off her breathing.

“No one can help you now!” he screamed at Brenda.

Brandon and Fielding had come out of the house to greet their mother, along with their teenage babysitter and the sitter’s boyfriend. The sitter rushed the children back into the house, but Kevin Harper, the boyfriend, tried to help Brenda.

“Stay your distance,” Ronald ordered. “If you don’t want to get shot, get out of here.”

Ronald flashed what Harper thought was a gun and he retreated. He, the sitter, Brandon and Fielding hopped a fence and made it to a neighbor’s back yard. “He’s shooting her,” the neighbor heard either Harper or the babysitter say, according to the Oxnard police report. “He killed her.”

The attack was reported to 911 as a shooting in progress.

Ronald finally wrested the purse away from Brenda. He found about $ 350 inside of it. He walked over to her car but didn’t get in. He returned and choked her again before running away as the sirens grew louder.

Pools of blood surrounded Brenda as she lay on the ground in front of her home. Medics loaded her into the ambulance. A police sergeant instructed a young officer to ride with her to St. John’s Regional Medical Center. He told the cop to get a “dying declaration” from the woman.

On the five-mile ride to the hospital, Brenda’s heart pounded at 150 beats per minute, about a third faster than normal. During the assault, she had bitten into her tongue, which was swollen and would have prevented her from talking if she was able to do so. She flailed about and was placed in arm and leg restraints.

At the hospital, doctors determined Brenda hadn’t been shot. She was suffering from oxygen deprivation from strangulation. Bizarrely, Oxnard police later charged her with being under the influence of a controlled substance, an allegation that prosecutors dropped.

Sunny Sung/LAT

Family and friends rushed to the hospital. Willingham says young Brandon came up to him at the hospital and made a surprising comment.

“That wasn’t my dad,” Brandon said, according to Willingham. “My dad wouldn’t do that to my mom.” Brandon suggested the attacker must have been his dad’s identical twin, his uncle Donald.

Indeed, Oxnard police found a man hiding in a field about a half-mile from the crime scene who identified himself as Donald Anderson. But Willingham went to the Oxnard police station and was taken to a fenced-in area where the man was being held.

“That’s Ronald,” Willingham said.

It took a little while to sort out what had happened: Ronald, serving his six months for the earlier attack, had left jail on a work-release program and never reported back. The authorities eventually came looking for him. Donald saw that his brother was on the lam, and turned himself in, saying he was Ronald.

Just like the Army, law enforcement fell for it. But now both twins were in custody.

Around the same time Brenda was headed to confront her estranged husband, I was working as a reporter in Dayton, Ohio, and weighing whether to accept a job offer from the Los Angeles Times. If I took the job, I’d be a reporter in Ventura County. I was 28 and had been married to my high school sweetheart for nine years. We had a 7-year-old son, Dwayne Jr., and our daughter, Christian, was 5.

I called the editor of my newspaper, Max Jennings, and told him about the job offer. A Texan with a large personality, Jennings had taken me under his wing. He knew I wanted to try my hand at reporting for a bigger newspaper, so he suggested I consider the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, which, like the Dayton paper, was owned by Cox Enterprises. “Why would you go to Los Angeles with all that smog?” Jennings said. “That’s no place to raise your two little kids.”

I visited Atlanta out of respect to my mentor, but accepted the job in California.

Brenda Bills talks about the attempt on her life.

My wife and I leased a three-bedroom townhouse in East Ventura. We had wanted an area with a lot of diversity. But finding a diverse community with top public schools was a difficult match. Ventura had great schools and we settled for that.

Living across the street from us in a handicapped-accessible apartment was Willingham, the man who had befriended Brenda. I learned years later that after Ronald assaulted her, Brenda was worried about her safety and Willingham suggested she and her kids move in with him for protection.

She was moving across the street from the reporter who would be covering her estranged husband’s court case, the one in which she was the victim. But I just saw her as Willingham’s wife and had no idea about her connection to Ronald.

Our kids met and became friends quickly. My son said he couldn’t believe his eyes when he first saw Brandon. Brandon was Black like Dwayne Jr., and that was an oddity in our community. Brandon was also doing backflips and listening to Dr. Dre music and a Black man, Willingham, was watching over him.

“You know it’s weird because everybody else [in the neighborhood] was pretty much white,” Dwayne Jr. recalled.

“At the time, they reminded me of our family,” said Natalie, my kids’ mom and my wife at the time. “Our children were the same age and they seemed to be a nice little family. … We were happy that our kids – both families – had good kids to play with.”

Dennis Willingham on moving across the street from the reporter on the story.

“All four of us used to take [Fielding’s] wagon and go pick lemons and try to make lemonade and sell lemonade,” Dwayne Jr., now 35, recalled.

The two girls wore their hair in puffy twists with little barrettes at the end. “Me and Fielding would chase Dwayne and Brandon,” Christian said. “We’d interrupt whatever they had going on. When we weren’t doing that, Fielding and I would walk about the neighborhood with [Fielding’s] My Size Barbie. It’s a Barbie that’s like 3 and a half or 4 feet tall. It would have clothes and we’d put that Barbie in the wagon and go around the neighborhood like it was one of us.”

What was Brenda and Willingham’s relationship when we first met them? She was separated from Ronald. Brenda and Willingham told me last year that their relationship was platonic at that point – and grew to be romantic later. In 2020, Willingham also told me that he knew I was the reporter covering Ronald’s case.

Brenda recalls that Willingham had told her I was a journalist. Willingham says he and Brenda talked about it and decided just to be my friend. She didn’t want to be involved in the stories I was writing about the assault.

“I remember Brenda was always very nice and sweet,” said my daughter, who is now 33. “I’d go over their house and she was like a regular mom. … I wouldn’t even think anything traumatic ever happened to her. Dennis was nice. Wasn’t all up in our business, like you.”

We had no clue Brenda had faced any difficulties in her previous relationship. That’s generally not something neighbors would get into.

But I wasn’t just Brenda’s neighbor. Although I didn’t know it at the time, I was the reporter covering her story.

I first heard the name Ronald Anderson on Nov. 19, 1993, from a lawyer at the Ventura County courthouse where I was covering the criminal justice beat.

By the time I found out about his case, I had missed the trial: A jury had just convicted him of attempted murder, robbery and kidnapping for the attack on Brenda. I wrote a short story about his conviction based on information from the court file and an interview with the prosecutor. I couldn’t find either Ronald’s wife or his brother.

When Ronald’s sentencing day arrived on Jan. 4, 1994, I was one of the first people in the courtroom.

Donald told me how he and Ronald had been swapping places for decades, switching on girls, teachers and employers. He said going to jail for Ronald was nothing new for him. Donald said he was better equipped to handle jail than his brother.

A deputy brought Ronald into the courtroom. He was wearing a blue jail uniform and sat at a table with Neil Quinn, his attorney from the public defender’s office. Maeve Fox, the prosecutor who I had interviewed for the first story, sat across from the defense.

A rail separated the participants in the case from the public gallery. Only a handful of people were in the room and one of them was seated behind Ronald. It was his twin, Donald, whom prosecutors had decided not to charge. Their likeness was remarkable, from the skin tone to height to jawline.

Donald’s eyes moistened when Judge Charles Campbell sentenced his brother to 14 years in prison – 12 years for the attempted murder and one each on the other counts. Deputies cuffed Ronald’s hands behind him. As he was led back to jail, Ronald turned his head and looked at Donald, his neck straining. Both twins were shedding tears. After a few seconds, the deputies told Ronald to move it.

Donald slipped out of the courtroom as I was interviewing the attorneys. I caught up with him in the parking lot and introduced myself.

“The prosecutor told me you went to jail for your brother so y’all could collect insurance money after he killed Brenda,” I said.

“I love my sister-in-law,” Donald told me. “I’d never hurt her.”

We jumped into my car and drove a quarter of a mile to an apartment building across the street from the county jail.

“I moved here just a few months ago when my brother got locked up,” he said. “I wanted to be close to him. Every day, he looks out the window of the jail, and I do backflips for him. We used to do gymnastics back in Philadelphia.”

Donald told me how he and Ronald had been swapping places for decades, switching on girls, teachers and employers. He said going to jail for Ronald was nothing new for him. Donald said he was better equipped to handle jail than his brother.

“And if I could take my twin’s place now, I would do it.”

Then Donald told me about 1969, when he took Ronald’s place in South Korea.

I wrote a brief story about Ronald’s sentencing for the next day’s newspaper. Then, three days later on Jan. 7, the Los Angeles Times published my longer story on the life and times of Ronald and Donald Anderson, headlined, Brother’s Keeper. Readers all over the country and in Canada and the United Kingdom, where the story ran in various versions, were astonished that Donald would love Ronald so much that he would go to jail for him.

The twins’ story ended up featured on The Montel Williams Show, a nationally syndicated program seen by millions. Donald was on Williams’ couch in the studio with his older sister, Carolyn. Ronald called in from jail. The twins sang a song to their late mom Marie. Williams’ producers had asked me to fly to New York and appear on the show but my editors at the Los Angeles Times didn’t want me to do it.

Williams’ producers asked if I could help them find Ronald’s wife, Brenda. I told them I had tried but I had no idea where she was.

Not long after that episode aired in the winter of 1994, my neighbor Brenda walked to my front door and handed my wife a bag of strawberries from her produce business. If she knew anything about The Montel Williams Show or my search for Ronald’s wife, she didn’t say.

By the following August, I had returned to Dayton to become an editor at my old newspaper. The day we left, 9-year-old Brandon saw us off and gave my son a stuffed animal as a sign of their bond and all the memories they’d shared in our neighborhood.

A day after we left, Brenda and Willingham, now married, packed up the family’s belongings and moved from their two-bedroom apartment into the three-bedroom townhouse we had just vacated.

Tomorrow, “Part 3: The rise and fall of the strawberry queen.” Or binge-read the whole story today! 👇🏾

Part 3: The rise and fall of the strawberry queen

There was no mistaking the voice on the other end of the phone. Dave Yobs knew it was Brenda Willingham.

“Dave, I’m headed towards Calabasas,” she said. “Where do you want to meet?”

It was still years before Brenda’s son, Brandon, would become Grammy-winning recording artist Anderson .Paak. For now, she ran a wholesale strawberry business. Yobs had invested $ 10,000 in her company and, two weeks later, Brenda was showing up with a hefty return: $ 17,000.

“It was in cash,” Yobs, 62, told The Undefeated recently. “I didn’t want to meet at my office.”

Dwayne Bray/The Undefeated

It was also a 70% profit, which is unheard of on transactions only a couple of weeks old. Flipping those funds helped Brenda support a lavish lifestyle for Brandon and his three sisters. “I was making a good living for me and my kids,” Brenda, now 69, says matter-of-factly.

Throughout .Paak’s life, Brenda was always a pillar of support. With his approval, Brenda, Paak’s wife and other family members were interviewed about the family’s history. Brenda had never previously spoken on the record about her son. .Paak originally agreed to participate with this story as well, but last June, amid the social protests that roiled the streets of America, his spokeswoman said he’d changed his mind because the time wasn’t right for what she described as a story that involved “Black-on-Black crime.”

Since blowing up nearly six years ago, .Paak has praised his mom’s dedication to taking care of him and his younger sister. By the time he was in ninth grade, the family lived in some sweet digs – a six-bedroom mansion in the posh foothills of Ventura. But the good times didn’t last. In 2004, right after he graduated from high school, he had to change his priorities away from making music because Brenda was in legal trouble.

“I kind of jumped out of the music thing and started working,” he said on the podcast Rap Radar in 2016, “trying to find my way, you know. I did a lot of couch surfing. I did a lot of dead-end jobs.”

Those jobs included selling shoes at a store for Vans, a company he now reps. And working as a health care aide and at an online book warehouse. He was overweight – at one point he was up to 270 pounds – and used this time to change his eating habits, work out and drop 100 pounds, he’s told interviewers.

“The times that would hurt would be when I was working these s—ty jobs and my bosses would catch wind that I did music,” he told Marc Maron on the WTF podcast in 2019. “They were like, ‘You’re talented. What are you doing here?’ as they were giving me my schedule.”

All Anderson .Paak has ever wanted to do is perform.

Even as a toddler, his dancing drew admirers. Brenda recalls taking him to a wedding in Los Angeles in 1989. She lost sight of him for a moment and he was out on the dance floor. As he strutted and glided, the guests egged him on.

“I knew he could dance a little bit,” Brenda said. “But I had no idea that he would actually get in front of a bunch of strangers and dance.

Brenda Paak Bills

“Next thing I know, everybody is clapping for him, saying, ‘Go, Brandon! Go, Brandon! Go, Brandon!’ And that really just got him hyped up. He was about 3 and a half, maybe 4.”

Brenda and I were having breakfast at a Cracker Barrel in Atlanta, a couple months before a worldwide pandemic had been declared last year. She’s a petite woman, half Black and half Korean, with a soft, calm voice. She pauses and does the math in her head about her son’s age at the time of his dance at the wedding.

“No,” she said, “I don’t think he was 4 years old yet.

“What I couldn’t believe was he was totally unfazed by the attention,” she said, as she ate her one egg and two pancakes. “He didn’t have a shy bone. You know how, when kids get attention, all of a sudden they just stop or they’ll look around and say that’s enough or whatever. Not him. That was fuel to the fire. He just kept on going.”

By 12, Brandon had started drumming for his church and by 13 he was getting a regular paycheck for it. He dreamed of signing a record deal and selling out arenas.

By the time he was 17, though, it all came crashing down.

Brenda came into the strawberry business in her early 30s for a simple reason. She needed more money.

Brenda was born in 1951 in Seoul as Lo Soo Park. Her father was a Black American soldier and her mom was South Korean. Because of the cultural opprobrium then attached to being biracial, she was placed in an orphanage at age 5 when it was time for her to start school.

At the time, a couple from Oregon, Harry and Bertha Holt, had started an adoption service to place children like Park with families in America. Park was adopted by a Black military couple from Compton, California, and they renamed her Brenda. She was assigned a birthdate of July 4, 1951, Independence Day in her new homeland.

Her new parents, Andrew and Naomi Bills, adopted another child from Korea the following year and supplied both children with a lot of love and hugs. They told Brenda not to reflect too much on her past or think too much about her birth parents because her mom had put her up for adoption so she could have a better life in America. Eventually, the family moved from Compton to Oxnard. Brenda married a high school classmate and they lived in San Francisco for five years until she was pregnant with Roni, their first child, when they returned to Oxnard.

Brenda Paak Bills

By the early 1980s, she was a divorced mother of two daughters. She worked two jobs, assisting the city manager at Ventura City Hall and in the deli at Kmart. She began a third job on weekends at a local strawberry business called Saticoy Fruit Co. Charles Davis was the owner and her boss.

“She had this little gray Mazda station wagon and I filled it up [with berries] and said don’t come back until you sell them off,” Davis recalled. “And then around 6 o’clock in the evening she comes back with this little grin on the face, and they’re all gone.”

In no time, she became part owner and quit her other gigs. “She learned the business, very intelligent, very smart,” Davis said. In 1991, he stepped aside, making Brenda the sole owner, a rare distinction for a woman in the California produce industry. She worried that being a woman would work against her in the male-dominated farming industry. But she had an indefatigable work ethic and won over the farmers as she sold their fruit to grocery stores and eateries.

In the early ’90s, though, the business suffered as Anderson .Paak’s dad, Ronald Anderson, became addicted to crack cocaine and stole from Brenda. Ronald, who assaulted her in front of their two young children, ended up in prison for attempted murder. Brenda divorced Ronald and filed for bankruptcy. But she quickly remarried and mounted a business comeback.

Brenda married for a third time in 1994 and she and Dennis Willingham, her new husband, opened the doors on a company they named Sunshine Fresh Produce. He was listed as the chief executive officer and owner because Brenda had that bankruptcy in her past, but Brenda ran the company.

By 1998, Willingham and Brenda were pulling down six-figure salaries. Strawberries ranked among the state’s most valuable crops, and in Ventura County, where Brenda plied her trade, growers rang up around $ 230 million in annual sales, or about 27% of the state total.

Some people were excited to see a Black woman succeeding in the produce industry. She recalls an agriculture regulator in the mid-1990s telling her, “You’re the only woman in California that’s doing this to this magnitude. … You’re definitely the only Black woman in California doing this at this level.”

By 1997, Brenda and Willingham decided to do more than buy and sell berries. They wanted to grow their own in a venture they called Willingham Farms.

“I could make more money if I had my own direct berries,” Brenda told me. “Sometimes, [farmers] would take it out on me if their season didn’t go well. They’d start to try to raise the price on me. My price should never change.”

She and Willingham started by leasing 52 acres in Santa Maria, California, in the Santa Barbara County area, and added more land over the next few years. To pay the leases and operating costs for the farms, they decided, on the advice of a local lawyer, to solicit money from investors, Brenda said. Several middlemen also solicited investors on her behalf.

One of those investors was Yobs, a real estate agent and former minor league baseball player with the Chicago White Sox. In 2001, a friend of Brenda’s, who was also a middleman, was buying a house from Yobs. The connection was made and Yobs invested $ 5,000 and got $ 7,500 back in a week, he said. Then he invested $ 10,000 and received his original outlay back plus $ 7,000 more in just two weeks.

“She was like clockwork” with the returns, Yobs said. “And that’s why I got my parents involved. She’d call my dad and say, ‘Hey, I’m on my way. I got your money.’ ”

In 2002, he decided to up the ante. Court records show he put in more than a quarter of a million dollars. “The strawberry business,” Yobs told me, “is a gazillion dollars.”

Not long after opening Willingham Farms, the family moved into a $ 1 million home in Ventura. The new digs had close to 5,000 square feet and six bedrooms. One bedroom was converted into Brandon’s music studio, where he and his collaborators could practice night and day.

His younger sister Fielding was attending a parochial school, while Brandon was at a selective technology-focused high school in Ventura. Nothing seemed out of reach for the kids. For instance, when Brandon told his mom he needed a fancy piece of equipment to make and sell demo tapes, she forked over $ 5,000 for it. She believed that her hard work had earned her the right to make such purchases.

The family frequently drove to Vegas, bonding on the long car rides and then going to shows and meeting entertainers. Willingham, Brandon’s stepdad, says he won more than $ 3 million over several years playing the slots. “That was a getaway from working hard all the time, not being available for the kids,” Willingham said. “Brenda or me, we were working strawberries all the time. You have to stop and say, ‘Look, timeout, we’ve got to make time for these kids.’”

In 2016, Anderson .Paak told The Guardian: “We were in Vegas every weekend. My mom and step-pops were really good, and when you’re really good at gambling, you don’t pay for anything. Everything was on the house. We’d get all our meals free, all the room service. I’d bring my friends from school. It was just crazy rooms, dude – TVs coming up out of the floor …”

In 1993, Brenda had sent her daughters from her first marriage to live with their dad in Texas to get away from Ronald’s drug-addicted behavior. One of the girls, Camille, came back to California in 1995. She wasn’t pleased that her mom had remarried so quickly and had a low tolerance for the way Willingham talked about the family business.

“He made it seem like he was doing everything, like ‘I’m the one who is bringing in all the money. I’m the one who is the spearhead of this business,’ ” Camille said. “He made it seem like my mom was the tail and he was the head of the business. I’ve always known my mom for being in the strawberry business and you’re coming in and now you’re telling me you’re the one?”

“Let me speak the truth,” said Brenda’s mentor, Davis. “Brenda was in charge the whole way. Her husbands, boyfriends or whatever, she brought them into it. They didn’t know nothing about strawberries.”

Willingham, though, says that Willingham Farms became his passion. He was also trying to provide male guidance for Brandon, who only had his mom and sisters after his dad went to prison and disappeared from his life.

“We just wanted to take care of the family. We weren’t trying to get rich, man,” Willingham, now 62, said. “If that happens, I wouldn’t know what to do no way. I’ve never been rich before.”

Brenda was glad to have Camille back in the fold. With the long hours Brenda worked, Camille could help care for Fielding and Brandon. Fielding, two years younger than Brandon, was an easy, uncomplicated child.

Brandon could be a different story. For instance, he had horrible eating habits that led to him being overweight. At McDonald’s, Brandon would order a Big Mac and replace the fries with chicken nuggets and sauce as his side dish. At home, if he were hungry, he’d go into the fridge and eat a spoonful of mayonnaise, Camille says.

Brandon had another habit that irritated people: He made a bunch of weird sounds. When he was in elementary school, Brandon would beatbox and tap on furniture, especially tables. “The teachers started calling me saying that Brandon was disturbing the class because he was noisy,” Brenda said.

She spoke to her son about what the teachers were saying.

Brenda Paak Bills

“I said, ‘Brandon, why are you doing that? You can’t be making noises in the classroom. The teachers are getting really angry with you because they can’t do their job because you’re making noises.’ I said, ‘What kind of noises are you making because they were trying to explain it to me but it didn’t make sense.’ So he says to me, ‘Mom, it’s the music that I hear. I’m just doing the music that I hear.’ I said, ‘What music? Who’s playing music in the classroom?’ ‘Nobody, I can hear it in my head.’ ”

Brenda was confused at first, but Willingham got it. His father, Rev. Ruben Willingham, had been a renowned gospel singer with the Swanee Quintet. He understood that Brandon was displaying a musician’s inclination when he tapped on furniture to the sounds in his head.

Teachers were seeing those things as a distraction. Willingham saw them as God’s gift. Brandon had started experimenting with playing drums in the middle school band, so Willingham and Brenda bought him a practice drum pad. Then a starter drum kit. Then a full drum set.

“Dennis can play drums, too,” Brenda said. “He’s sitting there playing drums and Brandon is coming and watching and Brandon picks it up right away … I’ve never seen anybody adapt to something so quick, but there they go, both of them, playing drums and Brandon is getting better and better.

“I have to say the boy just got natural talent. Not embarrassed one bit. The harder it seems to be, he just proves that it seems so easy for him. He does it with ease. I don’t know where he got it from because his father Ronald tried very hard to be that person that Brandon is. But he was never that person.”

Her voice trails off and she repeats herself: “He was never that person.”

By age 12, Brandon was drumming for Evangelistic Missionary Baptist Church in Port Hueneme, California, by the Navy base that had brought Willingham to the area. One day, Brenda picked Brandon up at the church. As he got into the car, according to Brenda, he said, “Can you take me to Denny’s?”

“To Denny’s?”

“Yeah, I got my money.”

He’d received payment for playing the drums. At Denny’s, Brandon ordered a T-bone steak, devoured it and paid his tab. His mom stayed in the car, making calls on her cellphone.

By 13, he was drumming at the largest Black house of worship in Ventura County, St. Paul’s Baptist Church in Oxnard. J’Rese Mitchell, the music minister and organist, became Brandon’s friend and mentor.

“We became known as ‘two piece and a biscuit,’ ” Mitchell told me. “He would play the drums and I would play the organ. We would add some okra and some sweet potatoes and everything else because I had some cousins and we would just jam out. We would spend a lot of time together, whether it was at his house or at the church.”

“What I saw in him, honestly, was a passionate, gifted young man who, behind this contagious smile, had a passion beyond none other for drums and for music,” Mitchell said. “Everything was music. When he got behind those drums, you could tell that he was in one of his happy places.”

Brenda and Willingham picked a rotten time to start growing their own fruit.

The couple began accepting investments in 1998. The years 1997 and 1998 saw an El Nino weather pattern followed by a La Nina, which means that “after a very wet first half of 1998 with the El Nino, conditions turned much drier during late 1998 and 1999,” said Scott Stephens, a meteorologist with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Before the nasty weather, his mom had her businesses under control, Anderson .Paak has said.

“My mom never worked for nobody,” he said on The Breakfast Club in 2018. “She had her own produce business. And so when the season was good, it was good. It was plentiful. But if you had a couple rainy seasons, it would be all bad. And it would be like you’re back on the oodles and noodles.”

Brenda never had any formal training in budgeting or finance and she was promising some investors returns up to 100% in a year guaranteed by promissory notes, loan contracts and joint venture agreements. Authorities said later that all those deals were illegal because neither she nor Willingham possessed a license to sell registered securities.

Nov. 4, 2001, was a Sunday. The temperature hovered in the low 60s and a breeze blew in off the Pacific Ocean. Brandon was on the drums at St. Paul’s service that morning.

In the pews, there was a palpable buzz. Someone told Brandon there was a story in the Ventura County Star about his mom and stepdad. Investors were accusing the couple of defrauding them out of millions of dollars.

After church, an emotional Brandon got a ride home and stormed into Brenda’s bedroom.

“Mom! Someone at church said you’re a crook. Is that true?” Brandon said, according to his mom.

She had no good answer for him. Brenda and Willingham were in a world of trouble.

Dwayne Bray/The Undefeated

The paper reported that several investors had filed lawsuits accusing the couple of using money from new investors to pay off earlier investors and for personal expenses. The funds were supposed to be for purchasing berries from farmers, paying for the crops to be sprayed, buying plastic containers and covering labor costs. Brian Condon, a Los Angeles attorney who filed some of the lawsuits, was quoted as saying, “It’s very much a confidence game.” When I met up with him in the summer of 2019, Condon characterized the couple’s business as “a Ponzi scheme.”

Condon and I ate at The Nook Breakfast Spot, which is tucked in a mini mall off the Pacific Coast Highway in Lomita, California. “They were willing to take any amount of money from anybody,” said Condon, who adds that his clients were “working stiffs” who couldn’t afford the losses.

After the newspaper story was published, the district attorney’s office opened a criminal investigation into the business activities of the Willinghams and even examined the 2001 purchase of their home. The Willinghams had not told their mortgage company that Brenda had a previous bankruptcy or that they’d been successfully sued.

In July 2003, the California Department of Corporations issued a “desist and refrain” order, demanding that the couple stop accepting investments. By then, the Willinghams were in debt to more than 700 investors, most of whom Brenda told me that she never met.

In our interviews, Brenda said that she got in too deep in part because she allowed others to solicit funds. “Everybody was on a mission and everybody had their own agenda,” she said. “I’m accountable to the people who are growing for me. I’m accountable to the people who are investing with me. Now I’m told I’m accountable to the people who I don’t even know.”

She said she wanted to pay people back and felt the only way she could do that was to continue raising money.

“I pleaded guilty because I was guilty … I could not misrepresent myself one more time. I was like a crack addict myself. Only my addiction was to money.”

— Brenda Willingham after being charged with fraud

“He sent me a cease-and-desist order and I ignored it,” Brenda said. “And I told him I was going to ignore it.”

She violated the order in December 2003 and was arrested after trying to get $ 6,500 from a man who had invested with her earlier.

Brenda and Willingham were each charged with 78 counts of securities fraud and other white-collar crimes related to 36 investors. Some people had raided their retirement accounts, their kids’ college funds or had taken out second mortgages on their homes. Bail was initially set at $ 2 million each, and Brenda’s older daughters were scrambling to raise bail and look after their younger siblings, Brandon and Fielding. Brenda, on the other hand, says she felt she was guilty and should start serving her time.

“I found myself on the cold … floor of the Ventura County Jail,” she told me. “I laid face down and I prayed for God to take me into his custody. We all need someone to take them into their custody. He’s not judging us by what we did. He’s judging us by what’s in our heart.”

Brenda pleaded guilty to 22 counts of securities fraud, one count of grand theft and one count of failing to obey the desist and refrain order. She got a prison sentence of 15 years and is on the hook for more than $ 4 million in restitution.

“I pleaded guilty because I was guilty … I could not misrepresent myself one more time,” Brenda said. “I was like a crack addict myself. Only my addiction was to money.”

Willingham held out. To this day, he says he was railroaded. If the same circumstances had occurred in Los Angeles County, he says, the case would have been a civil matter rather than criminal.

“Nobody could say, ‘I talked to Dennis, and Dennis gave me, and Dennis said, or Dennis did anything,’ ” he told me over dinner in Augusta, Georgia, where he now lives. “Only thing they could say with me, ‘I wasn’t going to let y’all crush my wife.’ Why? Because I had a history of seeing her damaged to her last breath on this Earth, and I wasn’t going to let y’all do nothing to her. Why? Because if you hurt her, you’re going to destroy these two kids, and I can’t have that.”

But Eric Dobroth, the deputy district attorney who prosecuted Brenda and Willingham, says even though the state limited the prosecution to a few dozen victims, in reality around 700 investors were bilked. “You saw the bankruptcy filing, right?” he asked me when I reached him by phone as he drove to work in San Luis Obispo, California, where he is now the assistant district attorney. In their bankruptcy petition, the Willinghams listed debts to investors and other creditors of $ 36 million, against assets of a little more than $ 1 million.

“I’d be confident saying that L.A. County would prosecute this offense as criminal securities violations,” he said. Dobroth calls Brenda the “face person” for Sunshine Fresh Produce and Willingham Farms and says Willingham cashed millions of dollars of checks that investors had given to his wife. “You’d see a payment on the [million-dollar] house or you’d see all of a sudden Dennis is in Vegas, where he was a whale. People were wooing him. They’re comping him rooms and TVs and everything, trying to get him out there,” Dobroth told me. “He was the real deal for a while.”

Willingham languished in jail for nearly a year before pleading guilty to 20 counts of securities fraud and selling unqualified securities. A transcript of his sentencing shows that Superior Court Judge Edward Brodie was apoplectic over how so many people invested in the operation without doing more research.

“A lot of these people are incredibly educated, intelligent and so, yes, I suppose greed kept this thing rolling,” the judge said, “and it was rolling real good for a long time because people thought that they had found a pot of gold at the end of the rainbow, and what they ended up finding was their own personal bankruptcies.”

Brenda Bills on leaving her family for prison.

I reminded Dobroth of what the judge had said about investors failing to do their due diligence.

“This whole operation is run by greed,” Dobroth responded. “It’s greed on behalf of Brenda and Dennis. Greed on behalf of the investors. It falls under that auspice of, if it sounds too good to be true, it’s probably not true. You know, wouldn’t you and me love to throw down 30K and get like a 50% or a 100% return on that investment in two months? Are you kidding me? We’d be billionaires.”

Brenda, at 53, settled into prison. She became a teaching aide and earned an associate degree.

Willingham was 46 when he went in. Not long after he got to the Wasco State Prison, a guard shot an inmate in the head with a foam projectile and the inmate died.

“First day, dude just killed,” he said. “Did that just happen? I’m in the cell. Lord, how am I going to go to sleep tonight? I’m mad now. For real. Jesus gone out the door with the bullet, with the dead guy.”

He and Brenda divorced while they were in prison. After his release, Willingham went back to school and earned a bachelor’s degree.

By the time my former neighbors were sent away, my family and I had left Ohio and moved to Dallas, where I became a sports editor. One day when I got off work in 2005, I heard that my son had been in contact with Fielding through MySpace: She was doing fine, Brandon was trying to be a musician and Willingham and Brenda were in prison. I was stunned and immediately looked up their case. But I felt there was little else I could do.

Anderson .Paak talked about how his mom’s conviction affected him in the 2016 Rap Radar interview:

“We were all spoiled,” he said. “My moms took care of all of us. And when that happened it was the domino effect. Everything went haywire. I was making a lot of headway with music at the time. And I kind of put everything to the side. And felt like I should just go out and maybe go to work and try to lighten the load for my family.”

In the 2019 song “Saviers Road” from Oxnard, his third LP under his Anderson .Paak stage name, he raps about the struggles he had while Brenda was behind prison walls:

Ten years, been a minute / I was somewhere between givin’ up / And doin’ a sentence / God, if you existin’, help my momma get acquitted.

Tomorrow, “Part 4: From Breezy Lovejoy to rising star.” Or binge-read the whole story today! 👇🏾

Part 4: From Breezy Lovejoy to rising star

Before he became Anderson .Paak, Brandon Anderson was an aimless, twice-married, 25-year-old father of one living in his sister’s house and facing eviction.

“He didn’t pay rent for six months,” his sister, Camille Timan, was telling me. “I went to him and said, ‘You said you were going to move.’ And that very next day, he left.

“Ever since we were kids, I used to tell my brother, ‘You’re going to be famous. Just keep working on the music,’ ” recalled Timan, who is seven years older than her 35-year-old brother. “When he didn’t want to move, I told him I had a dream about him – that he was performing before thousands of people.”

Guilt-tripping her brother into moving out in 2011 was one of the best things to happen to him. She knew he was coasting by living at her spot and working on an illegal marijuana farm, with his music only an afterthought. She says she couldn’t stand to see him waste his God-given talent.

Anderson .Paak took up the challenge. He moved his small family 40 miles south to Los Angeles even though he had no car and no place to live. He leaned on friends until he could land steady work as a musician.

One thing led to another. He got work playing drums for some headliners on tour and television. A mentor paid for him to hole up in a studio for six months. He collaborated with other musicians and, less than a decade later, ended up with a record deal, several smash albums and three Grammy Awards. He’s nominated for two more this weekend.

That has been the pattern for .Paak. He has had a life full of fits and starts. Ugly things kept on happening. Family snatched away. Dreams dashed.

In high school in Ventura, he was gaining traction on the local music scene as a DJ, producer and drummer. He figured he could be the next breakthrough star for Roc-A-Fella Records, maybe the next Kanye West. And then one day during his senior year in December 2003, his mother was arrested. Brenda would stay locked up until he was 25, married and a father.

Ethan Miller/Getty Images

It was the second time that one of his parents was taken from him. When Brandon Anderson was 7, his dad was sentenced to prison for 14 years for trying to strangle his wife to death in the driveway of their home.

Yet, whenever one person faded out of his life, another would come into it. After his father’s conviction, his mom quickly remarried and his stepfather bought the then-12-year-old a starter drum set.

The boy was acting out in school and at home. Introducing his stepson to drums was a way for Dennis Willingham to channel the boy’s energy. “My father had already told me I had to break the cycle of addiction for Brandon and Fielding,” Willingham said, referring to Anderson .Paak and his younger sister.

“No matter what he did, he always had some kind of support out there to encourage him,” said his mom. “Even if it wasn’t me physically, he always knew that I would want him to keep going. He had his sisters that knew his worth. When kids are surrounded by love and support, that could be the thing that keeps them going.”

In the mid-2000s, Brandon was performing under the stage name Breezy Lovejoy and living the life of a starving artist. He went to Musicians Institute in Los Angeles but dropped out because he couldn’t afford the tuition. The school let him stay on as a teaching assistant. He was often without a permanent home and squatted where he could.

He and some students started a band that sometimes had to pay just to play at a venue. Brandon had a raspy voice and had previously shied away from singing. But he picked up vocals, besides playing the drums, so the four-man group wouldn’t have to split its measly pay a fifth way. That made him the rare hip-hop artist who not only was backed by a full band but was also an instrumentalist and the vocal lead.

Brenda Paak Bills

His older sister, September, recalls those early days in the 2000s: “I used to go to his shows, me and my friends, when he was Breezy Lovejoy. Drive from San Diego, go up to LA, wherever he’s at, that’s where we were at. He had a show out here in San Diego. I love his music. It’s just very versatile. It’s got a whole lot of flavor. A whole lot of flavor.”

In November 2010, Brandon found out his girlfriend, Jaylyn Chang, a student at the music school, was pregnant and they decided to marry. It was more of a mutual agreement than a marriage proposal by either party. “When I got pregnant, it just happened,” said Chang, who, like Brandon’s mother, was born in Korea. “We got married at a label services center office that specializes in immigration.”

(On the song, “Without You” from his album Malibu, he sings, “Papa said, ‘When I get older, get a girl like your mama.’ ” It was actually Anderson .Paak’s second marriage. The first one, when he was 21, yielded no children and ended quickly.)

At the same time Chang was expecting, the girlfriend of his band’s guitarist, Jose Rios, was having a baby as well. Brandon Anderson and Rios needed paying jobs. Rios called up a friend who was involved with an illegal weed farm in Santa Barbara.

“Man, I got no money and I just had a kid,” Rios told the pot entrepreneur.

“Come up to Santa Barbara, bro,” the man said.

“I got my friend, Breezy, too, man. Is it cool if I bring him?”

The musicians were now farmhands. They chopped, hung, trimmed and bagged pounds and pounds of marijuana. If they stayed on the farm and slept in the stash house, they could make up to $ 5,000 a week. If they worked regular hours, they’d make around $ 3,000 a week.