Europa, 2008, Nandipha Mntambo, Swazi, born 1982. Exhibition print 311/2 ×311/2 in. (80 ×80 cm). Photographic composite by Tony Meintjes. Loan from the artist and STEVENSON, Cape Town and Johannesburg. The Western mythos around masks is familiar, unconcealed. Don a disguise, whether a helmet for a sports match or a costume for a masquerade, and be liberated, freed from a fixed identity and thrown into a space with limitless potential. We often transfer a similar understanding onto the masks worn in African rituals, conjuring visions of supernatural transformations in which the self is abandoned under the cloak of disguise. However, this kind of interpretation requires the wearer of said disguise have a fixed identity to begin with, a stable place from which to depart. What happens when such foundations are…

The Western mythos around masks is familiar, unconcealed. Don a disguise, whether a helmet for a sports match or a costume for a masquerade, and be liberated, freed from a fixed identity and thrown into a space with limitless potential.

We often transfer a similar understanding onto the masks worn in African rituals, conjuring visions of supernatural transformations in which the self is abandoned under the cloak of disguise. However, this kind of interpretation requires the wearer of said disguise have a fixed identity to begin with, a stable place from which to depart. What happens when such foundations are complicated, and Western fantasies disturbed?

A group exhibition at the Seattle Museum of Art entitled “Disguise: Masks and Global African Art” aims to dismantle our concepts of identity and disguise, commissioning eight artists from Africa and of African descent to address the present and future language of masks, veils, cloaks and screens.

Masks of wood and fiber from the SAM collection are propped against contemporary facades incorporating video glitches, immersive environments, and virtual reality. Viewers are prompted to question: How do contemporary artists visualize the lasting human desire to hide from each other and ourselves? What role do such disguises play in understanding gender, race, origin and identity; hybridity, queerness, in-betweenness, becoming?

Pamela McClusky, who curated the exhibition along with Erika Dalya Massaquoi, was partially raised in West Africa, growing up around masquerades. “I always thought people didn’t really understand them,” she explained in an interview with The Huffington Post. “Museums tend to collect masks but not full masquerades. I always felt they didn’t know what they’re missing.”

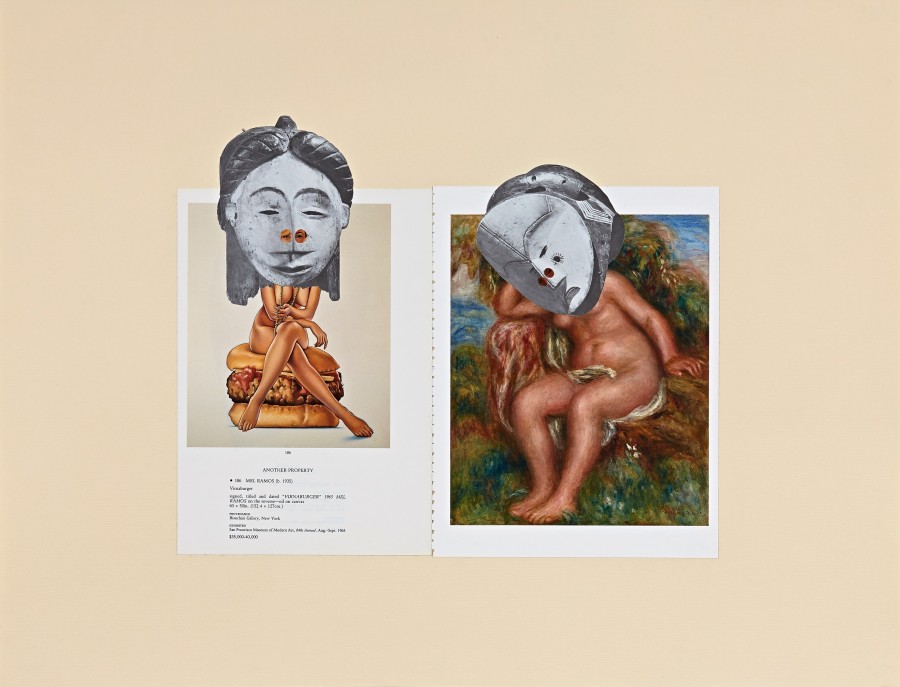

McClusky was also skeptical of the ways African masks were most commonly integrated into Western culture, via artists with little knowledge of their origins and purpose. “I also have a little bit of a vengeance streak against Picasso and that era where they put masks on naked bodies in works like ‘Les Demoiselles d’Avignon.’ It was an aberration to the African context they came out of.”

Traditionally, African masks are made to be worn as part of masquerades, rites central to many (but not all) healing and problem-solving rituals. Many of such masks reside in the SAM, plucked from their former lives as performative vessels and plopped into the white walls of the museum, to be carefully examined but never touched. Visitors encounter these ritual objects, casting onto them a self-fashioned understanding of their original purpose. However, often these stories fail to encapsulate the true purpose of the masks, revealing more about viewer than work.

Additionally, the normally sterile and hegemonic setting of the museum space isn’t the most compatible with the vibrant aura of the masks. “I think for a lot of people museums have an austere sensory diet that you go on when you walk in where you look at one thing at a time,” McClusky said.

In response, the curator remixed the traditional museum setup, allowing past and present interpretations of disguise to reverberate off each other. While viewers walk through “Disguise,” a soundtrack plays in the background, turning the galleries into immersive environments with plenty of play between African masks and their contemporary counterparts. “In one gallery, we set up four older masks and they’re looking at screens of 21st-century masks that are adapted from their image, so it looks like the masks have been watching TV all day.”

The artists on view each communicate a distinct worldview and relationship to the notion of disguise. Jacolby Satterwhite crafts virtual masquerades based on his mother’s impossible inventions, while Walter Oltmann crafts ornate wire sculptures which catalyze metamorphosis. Each artist disrupts the standard narrative of a mask as a means of liberation or escape, instead questioning what additional factors contributed to this mythology as the conventional understanding of disguise.

What happens when African authenticity mingles and merges with Western fantasy? And does such an authentic African identity even exist? This question is at the center of artist Brendan Fernandes‘ work. “I grew up in Kenya. My family moved to Canada, and now I live in the U.S., so I’ve always been negotiating this idea of identity,” Fernandes explained to HuffPost. “People always ask, who are you, where are you from? And I’m from a lot of places. Identity is something that is constantly changing and in flux. We want them to be static, but they’re always changing and moving. Because of that, I use the term ‘authenticity’ a little bit tongue-in-cheek.”

For “Disguise’s Neo Primitivism 2,” Fernandes unleashed a herd of 12 fiberglass deer, all donning identical white resin masks, throughout the gallery. “The masks were bought on Canal Street and cast into these plastic kids party masks,” Fernandes said. “And then there are the fake deer, which are used in hunting to attract real deer. So we have two fake objects. The mask itself embodies the political attributes of a Kenyan nomadic male warrior, but in Kenyan tradition we don’t wear masks. So somebody made this mask up and sold it as a souvenir in an African market on Canal St. These fake masks that have their own identity that’s made up and created. How is that real? How is that authentic?”

And yet, together, the fake deer and the fake mask form a new creature, an original amalgamation of fakeness. “When you put the mask onto the deer, it takes away the decoy function of the deer. It becomes a hybrid. Hybridity is something I’m contemplating. The idea of becoming, queering, a transitional space.”

Hybridity also serves as a central concept for artist Saya Woolfalk, whose multimedia works revolve around a mythical species called “The Empathics.” The virtually crafted hybrid breed, part plant and part animal, are an impressionable bunch, to say the least. Woolfalk’s species literally absorbs its cultural influences and physically mutates as a result. “The Empathics,” much like many Americans, are constantly shifting, digesting and evolving in reaction to external influences.

For Woolfalk, whose father is African American and white and whose mother is Japanese, masks aren’t just disguises, they’re body parts, launching pads. “My work has to do with the aspirational embodiment of something that we may or may not inhabit yet,” Woolfalk explained. “The idea of masking isn’t necessarily this sort of — performing an identity.”

“For this project, I thought a lot about ideas of diaspora. What is the diasporic notion of a performance? What does it mean to be a contemporary global citizen? How can an installation make someone feel the way a global citizen might feel if they weren’t displaced, if they were actually located and welcomed?”

Woolfalk’s video, somewhere between a children’s science performance and a psychedelic drug trip, allows viewers to enter into this state of hybridization, eating up cultural stimuli and reflecting them accordingly. “When I talk about a global citizen, I’m not talking about the people who fly around from place to place. It’s the idea that we’re constantly changing, responding to the influx of the people that we encounter on a day-to-day basis. I mean people who are constantly changing responsibly to the myriad people of cultures around the world.”

“Disguise is a common phenomenon that we all share,” McClusky said. “But artists are showing us ways to work with that within in a multitude of media, and are able to give us suggestions of ways to rework that side of our lives.” The simple trope of mask as escape doesn’t quite hold up to the 21st-century notions of identity and origin. The artists of “Disguise” reveal other ways to hide, to play, to shape-shift, to pretend, to erase: all without showing your face.

The exhibition runs until Sept. 7, 2015, at the Seattle Art Museum, and then will travel to the Fowler Museum at UCLA from Oct. 18, 2015, to March 13, 2016, and to the Brooklyn Museum from April 22 to September 11, 2016.

— This feed and its contents are the property of The Huffington Post, and use is subject to our terms. It may be used for personal consumption, but may not be distributed on a website.

![]()

![]()

See more here:

Global African Artists Explore The Meaning Of Disguise In The 21st Century