In 1990, a man named El Anatsui was among the first batch of sub-Saharan Africans ever to present at the Venice Bienniale, the grand ball of the art world. By 2007, the Ghanaian artist was the beau of the very same ball, having transformed the end of the Bienniale’s main hall, the Arsenale, into a corridor of disorienting light, beamed off the sort of ingenious piece that would become his calling card: a suspended sheet woven of flattened liquor bottle caps. Anatsui’s new work looks familiar, but tackles fresh concerns. The New York Times declared him a “global star,” one of a few African artists on which every …

In 1990, a man named El Anatsui was among the first batch of sub-Saharan Africans ever to present at the Venice Bienniale, the grand ball of the art world. By 2007, the Ghanaian artist was the beau of the very same ball, having transformed the end of the Bienniale’s main hall, the Arsenale, into a corridor of disorienting light, beamed off the sort of ingenious piece that would become his calling card: a suspended sheet woven of flattened liquor bottle caps.

The New York Times declared him a “global star,” one of a few African artists on which every critic in the Western world is compelled to make some kind of judgment. In Anatsui’s case, the reviews tended to be as glittery as the work — witness the blitz surrounding his sweeping retrospective last year at the Brooklyn Museum of Art, the launch of which prompted the Times anointment. His, after all, are beautiful sculptures rich with innuendo, not only about the detrimental effects of colonization (European countries were the first to introduce, and reap handsome profits from, the sale of liquor in parts of Africa — a continent now plagued by alcoholism), but also in terms of environmental concerns such as recycling and waste. Then there is the poetic commentary on the shiftiness of a work of art: Anatsui’s are made with much help from local workers, and draped according to the whims of each setting’s curators.

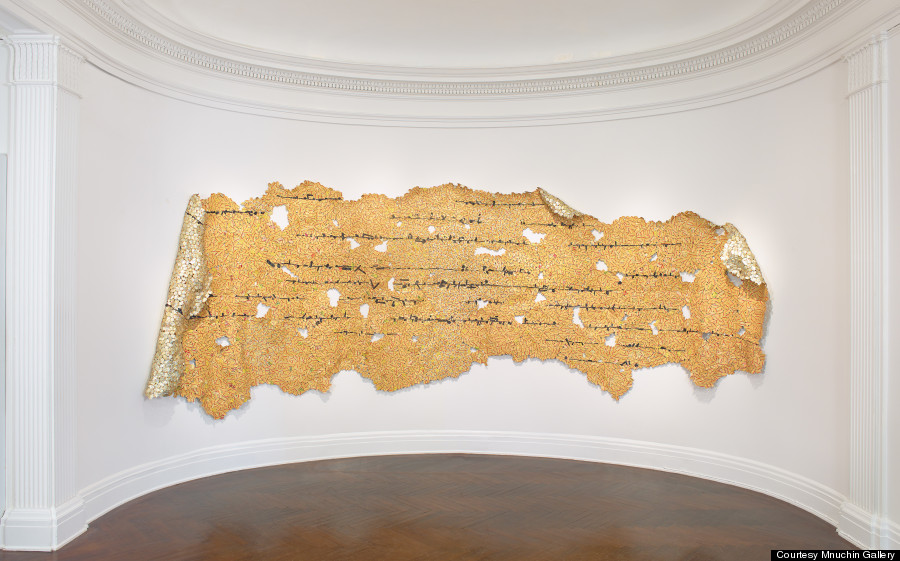

But a new show overturns many of those expectations. One year later, Anatsui has picked a wholly unpredictable setting to debut a quietly daring exhibit. “Metas,” at the Mnuchin Gallery in Manhattan’s Upper East Side, might at first glance seem to present more of the same: Bottle caps? Check. A closer look, however, reveals an artist grappling with the fixations of a different place and era than his own.

From a series of flattened steel plates to sculptures strung of caps of a single color, the works at Mnuchin represent an artistic “leap,” says Sukanya Rangarajan, a partner at the gallery who worked closely with Anatsui on the exhibit. The conversation begun in Venice is morphing into “a more art historical dialogue,” in Rangarajan’s assessment, one that loops in the voices of American minimalists like Donald Judd (the subject of a recent exhibit at Mnuchin), and 20th century European cubists.

What were once shimmering portals into African history are now experiments in form and line. Just as Pablo Picasso entered a blue period as a way to explore the dimensions of a single color, Anatsui is “moving away from color into a grey palette,” Rangarajan points out. Pinned onto the walls of Mnuchin — an unconventional gallery space, set inside a townhouse — these new bottle cap sculptures recall the oeuvre of artists not typically associated with Anatsui. The clarity of geometry and color, the shocking simplicity of the work’s direct placement onto the walls, it all calls to mind the phenomenon of Kazimir Malevich, the Russian abstract expressionist who in 1915 stunned war-weary audiences with the purity of the first totally non-representational painting in Western art, titled simply, Black Square. The subversion here is circumstantially different. Set against the townhouse’s innate decorum, Anatsui’s sculptures seem vaguely revolutionary, the gallery version of a child’s wild scrawls on the walls of the wealthy parents’ brand new home.

Anatsui was inspired in part by the space itself, according to gallery notes. The historic townhouse is full of the sort of architectural details popular in romantic comedies set in New York City: high molding, a grand rotunda, and an arched stairway curling up the building’s three floors. According to Rajaratnam, Anatsui welcomed the chance to design for a space so different from any he’d shown in, where the simple fact of the juxtaposition of his work inside creates drama.

A few pieces span curved walls. One clings to the stairwell side, like some sort of jewel-encrusted cobweb, creating what Rajaratnam calls an “interface with the environment.” Anatsui typically builds work that can be folded into a suitcase and shown anywhere, but these works are meant for Mnuchin. It’s an ideal match. “We are not a traditional white box,” Rajaratnam says. “And El is not your typical artist.”

Metas is presented in collaboration with the Jack Shainman Gallery, and runs through Dec. 13 at the Mnuchin Gallery.

Read the article: