Mitchell S Jackson

In his provocative new video This is America, Donald Glover, as his hip-hop alias Childish Gambino, artfully uses the surreal to comment on black lives

Once upon a night in my black life, I bought a 9mm Glock 16 replete with an extended clip off the street, bought it because I’d been robbed for the drugs I sold a time or two and decided against being a mark again, that the next dude that tried me would suffer bullets.

Decades ago, that was my America. Decades later, it’s an America that still exists for untold others. And though that shouldn’t be news, it’s a truth worth reminding us. In his artful and provocative new video This is America, Donald Glover, as his hip-hop alias Childish Gambino, attests to as much: “Yeah, this is America (woo ayy) / Guns in my area (word, my area) I got the strap (ayy, ayy) / I gotta carry ’em.”

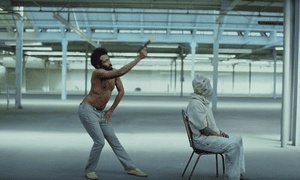

The film is directed by Hiro Murai, Glover’s frequent collaborator on Atlanta, and it is indeed ballistic. It begins in a warehouse with the artist Calvin the Second shown seated and strumming a guitar while choral sounds and choir voices sing: “We just wanna party.” Glover, who has been in the background dances over, bare-chested, mimicking the expressions and gestures of a minstrel. He proceeds to pull a gun from his waistband and shoot Calvin in the back of his now bag-covered head. After that murder, Glover shouts “This is America”, and the music shifts from the choral sounds to a trap music baseline.

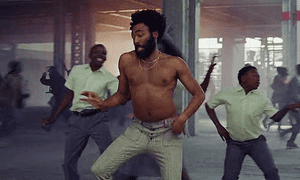

A crew of school uniform-clad children join Glover and together they perform a choreographed routine that features a panoply of dances including Atlanta’s whip and the South African Gwara Gwara. For most of the video, Glover and the schoolchildren keep right on boogying in seeming obliviousness, while a riot suggestive of several cultural and historical references erupts behind them.

Near the middle of the video, Glover side-moonwalks into a room while a choir in faux jubilance sings: “Get your money, black man (get your money).” Someone off-screen tosses Glover an assault rifle and, in a scene suggestive of the Charleston mass shooting, Glover massacres the choir members and decamps while a mass of people rush into the room.

Later moments of the video show Glover and his gleeful dance crew grooving again, and also a solo of him channeling Michael Jackson on the roof of an old car – all of which is still backdropped by symbol-laden mayhem. At the end of the video, Glover is shown running in a dark room from a blurry mob of white folks.

The video was released after Glover’s hosting and performing duties on the most recent Saturday Night Live. At the time I write this, it has racked up upwards of 47m views as well as dozens of published critiques and umpteen social media posts. The responses have been passionate. Dear White People creator Justin Simien wrote an essay in Twitter posts proclaiming its artistic merits, and scores of celebrities have lauded it with superlatives: “iconic”, “brilliant”, “genius”. A smaller number of viewers, however, have been critical of the video, voicing among their concerns, the morality of Glover’s motives, the effect of portraying gratuitous violence, the wisdom of summoning images of Jim Crow in America’s charged racial climate.

For the record, I’m closer to the former camp than the latter, but what’s more important to me than arguing Glover’s brilliance or lack thereof, is interrogating his use of the surreal as an aesthetic to comment on black lives.In his seminal essay Manifesto of Surrealism, the poet and top propagandist for the surrealist movement André Breton describes surrealism as a resolution of what appears, prima facie, as the contradictory states of dream and reality into “a kind of absolute reality, a surreality”. Given this definition, surrealism seems an apt tool for expressing some of the trauma of black life, one that can provide means of portraying what can feel at once like an out-of-this-world nightmare and the far too commonplace.

Breton further defines surrealism as expression that is “psychic automatism in its pure state”, one absent of the control of reason or aesthetic or moral concern. At first glance, an automated response devoid of reason or moral concern describes the often fraught treatment of blacks by whites, actions that can’t be defended as reasonable or moral. The full definition of surrealism becomes a way to describe the “absolute reality” that exists at the intersection of black and white lives, which is to say our America. Part of Glover’s brilliance is his resistance to using his work to proselytize or offer advice on how to reconcile the America made of our disparate experiences within its borders. Instead, he invites his audience to examine both the fore and background of their lives, to pose questions.

There’s much to see and ask of This is America. The day after it was released I watched it numerous times, each time encouraged by noticing a detail I hadn’t caught the previous time. There’s the hooded figure galloping across the background on the white horse of death, a police car trailing behind him. Is Glover reminding me of the crisis of police shootings? There are the young men, high in the rafters, filming the riot below on their cellphones. Might this be Glover suggesting our complicity in commodifying suffering? There’s the (black?) woman at the end of video, paces behind him, also sprinting from the white mob. Should I read this as the implication that black men can’t provide the protection our women deserve because we’re too busy running from angry white power?

Through it all, Glover danced and danced and danced. Should his performance serve as a reminder of the role dance has played in black lives since our captured ancestors were forced to dance on slave ships during the middle passage? I’m not sure, but what I know is that the more I watched the surreal violent images of This is America, the more I reflected on my relationship to what I’d witnessed.

Which brought me back to the illegal Glock I mentioned at the outset. In the midst of attempted home invasion, I ran to retrieve it and it was gone, stolen I’d find out later. In a moment that felt every bit an anomaly of my known world and fate, I stood panicked as who-knows-who boomed kicks against my back door. Lucky for me, a white neighbor heard them too, and scared off the would-be robbers by threatening to call the police. Calling the police never once crossed my mind. And that, too, is proof of America. Mine and his. Yours?

- Mitchell S Jackson is author of the novel The Residue Years and the forthcoming essay collection Survival Math: Notes on an All-American Family

Since you’re here …

… we have a small favour to ask. More people are reading the Guardian than ever but advertising revenues across the media are falling fast. And unlike many news organisations, we haven’t put up a paywall – we want to keep our journalism as open as we can. So you can see why we need to ask for your help. The Guardian’s independent, investigative journalism takes a lot of time, money and hard work to produce. But we do it because we believe our perspective matters – because it might well be your perspective, too.