About 15 years ago, Paul Haggis was laughed out of one meeting after the next when he pitched “Crash” to television executives. He wrote it as a movie instead (with Bobby Moresco), but pre-production was shut down multiple times because the cast didn’t include the right A-listers to justify financing. After it was finally made, Haggis tried, unsuccessfully, to talk Lionsgate out of a wide theatrical bow, thinking its box-office potential would wane without time to generate buzz in limited release. The movie grossed an impressive $98 million worldwide, but Haggis nonetheless tried to convince the studio that an attempted Oscar campaign would be mortifying. Then the movie won Best Picture. Ten years later, “Crash” is one of the most contentious releases of the past …

About 15 years ago, Paul Haggis was laughed out of one meeting after the next when he pitched “Crash” to television executives. He wrote it as a movie instead (with Bobby Moresco), but pre-production was shut down multiple times because the cast didn’t include the right A-listers to justify financing. After it was finally made, Haggis tried, unsuccessfully, to talk Lionsgate out of a wide theatrical bow, thinking its box-office potential would wane without time to generate buzz in limited release. The movie grossed an impressive $98 million worldwide, but Haggis nonetheless tried to convince the studio that an attempted Oscar campaign would be mortifying. Then the movie won Best Picture.

Ten years later, “Crash” is one of the most contentious releases of the past decade. Even though a few initial detractors saw the movie as “dramaturgical pixie dust” and characterized it as “at once tangled and threadbare,” “Crash” received mostly glowing reviews and gained steady momentum as competition for that year’s Oscar front-runner, “Brokeback Mountain.” To combat the movie’s awards-averse May release, Lionsgate distributed 130,000 copies of the DVD to voters, targeting actors because they comprise the Academy’s largest branch. “Crash” nabbed the Screen Actors Guild Awards’ top prize, and when “Brokeback” failed to receive a Best Film Editing nomination — a statistical prerequisite for Best Picture — it seemed the film’s Oscar fate was more or less sealed.

Yet we are still weighing the merits of “Crash” to this day. TIME listed its contest with “Brokeback Mountain” as one of the most controversial Best Picture races in Oscar history, while debates rage on regarding its presentation of American racial tensions. But Haggis, whose celebrity status has risen following his Scientology resignation and participation in the documentary “Going Clear,” is perfectly aware of how some feel about his film. Following Haggis’ two decades in television (he wrote for “The Facts of Life” and “L.A. Law” before creating “Walker, Texas Ranger” and “Family Law”) and his success as a screenwriter on 2005 Oscar-winner “Million Dollar Baby,” “Crash” became so polarizing that its legacy will forever follow Haggis — as will the two Oscars he received for it (the other was for Best Original Screenplay). A decade after it opened in theaters on May 6, 2005, The Huffington Post spent an hour chatting with Haggis about the making of “Crash” and its reputation.

What was the genesis of “Crash”?

It originated in a dream that I had. I woke up in the middle of the night thinking about these two guys who 10 years before had jacked my car. I was really curious about who these two kids were. It stuck with me and I just wanted to know what their relationship was to each other. Were they friends? Had they just met that night? Was it something they did a lot? I decided to go into my study and just write about them. And then — this is like 2:30 in the morning — I asked myself, “Who did they meet?” Well, me and my wife. “What did we do?” We went home and changed the locks in the middle of the night. Hmm. “Well, who did we meet?” We met the locksmith. It just kept going like that, so that by 9 a.m., I had the whole plot and all the characters. Then, being a television guy, I thought it was a television show, so I got it together and I took it around to the networks and pitched it. Of course, they didn’t want it. The last thing they wanted was a series about race and intolerance in Los Angeles.

After networks turned you down, you took the outline and recruited Bobby Moresco to help you turn it into a movie. Studios weren’t interested, and securing financing was hard. Was that because it revolved around race?

I was a complete unknown. In fact, I was worse than unknown — I was a television guy. Fifteen years ago, there was a huge stigma against television writers and directors moving into film. “Crash” is about intolerance and the lack of connection in the city. It’s a movie that, at its heart, by design, doesn’t bust those terrible racists from down South. No, the people who pay the biggest price in this movie are the people who think they know who they are, who have this pride and think they’re good people. So, liberals. And it was fascinating when this film came out because I remember the bad reviews — I think one in The Hollywood Reporter said, and I’m paraphrasing from memory, “If this film had been made 10 years ago, we would call it ‘brave’ and ‘timely,’ but we don’t have these problems anymore.” The week that I was reading that, there was a race riot at Santa Monica High School. But as liberals, we all like to think that we would solve these problems, or that we have solved these problems. Otherwise we can’t live with ourselves, and that hubris is what I wanted to write about it. So you can understand why people didn’t want it. In fact, the people who are like Matt Dillon’s character, who are obviously racist, actually had a chance at glimpsing themselves and changing. It’s the folks in denial like you and me who were fucked.

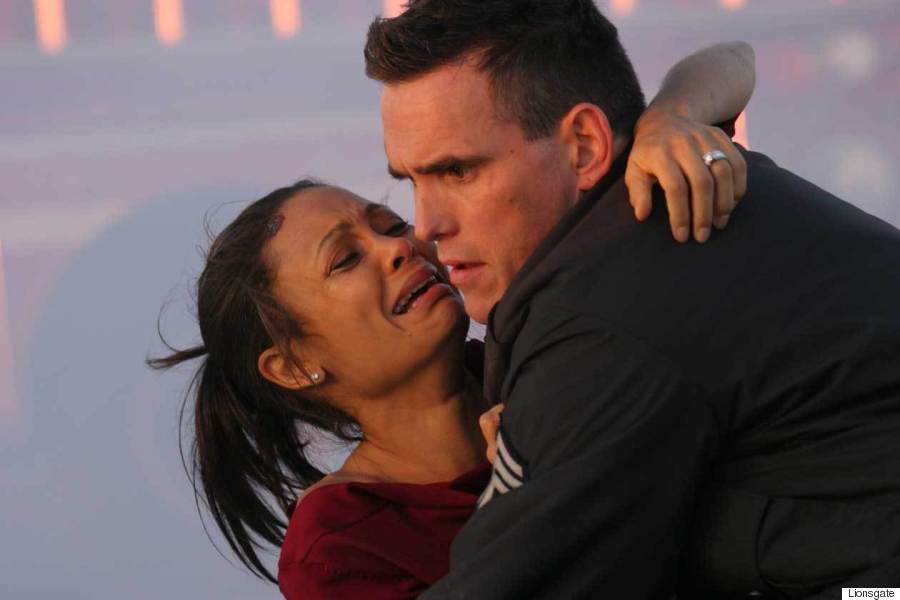

Thandie Newton and Matt Dillon in a scene from “Crash”

Did you accomplish what you wanted to?

It was a social experiment. I wanted to fuck with people. I was tired of my friends and people I worked with being unable to see everything that was around us. It was so obvious to me, and I think it was so obvious to me only because I’m a Canadian who didn’t grow up with everything else that was around us. It’s good to be an outsider. You’re just a half a step back from everybody else. It’s not that you’re an alien; people will accept you into the group, but you see things that people just don’t notice. And I’m not talking earth-shaking; I saw a lot of small, unsettling moments over my time in Los Angeles. And I participated in those. I wanted to bust myself. Why was it that I was walking down the street in Westwood on a nice night and I see three or four young black guys in hoodies walking towards me, having a good time and joking around, and I cross the street? How can I do that? I’m mad at myself as a liberal. So I wanted to explore that. It’s that sense of hypocrisy and pride that we struggle with as human beings. I thought on that level the film succeeded very well. I remember at one screening I was standing with the cast against a wall waiting to go up and do the Q&A. The movie ends and the credits roll, and this big guy comes down immediately and bolts out of the theater. He’s got long hair and chains and looks like a biker. He sees Don Cheadle standing beside me and he sees Matt Dillon, and he pauses. He stares at me and says, “Do you have something to do with this film?” And I said, “Yeah, I did.” He said, “The movie just changed my life.” And he turned and walked out, like he was embarrassed. I’ve heard that time and time again, and I was very proud to be part of a film that had that kind of reaction.

It feels like you incorporate just about every racial group in L.A. Was that intentional?

No, it just fell together that way. I was working on our fear of strangers, obviously, and this ridiculous theory that I’d come up with. When Third Street Promenade was being built in Santa Monica, I was there before that and I remember Third Street was just an abandoned street. They put some money in, opened a couple of theaters, a couple of restaurants, and suddenly it’s packed with thousands of people. I’d walk down the street and go, “What the hell is this? There are people from all parts of the city and all walks of life.” So if you ask somebody what they’re doing there, they’d say they’d come for dinner or a movie, but you know what? There are restaurants and movie theaters much closer to where they live, so that’s bullshit. So I said, “Why? Why are they coming here?” And I came up with this ridiculous theory, which was that, as human beings, on a genetic level, we need the touch of strangers. We need it on some primordial level, and if we don’t get it and we isolate ourselves, we become angry and the isolation destroys our soul. So I came up with that bullshit theory, because that’s what you do as a writer, and then played it out.

Did people tell you that, as a white man, you shouldn’t be making a movie about race?

Yes, constantly. In fact, after making “Crash,” because I had my heart attack and we had to shut down for a few weeks, we lost Don Cheadle to “Hotel Rwanda.” We had to wait four months for him to come back so we could complete it. I remember I went to see the premiere of “Hotel Rwanda” at the Toronto Film Festival, and I went up to Terry George afterward, who I’d never met, and said, “How did you have the balls to make this movie?” A white Irish guy making a story about Rwanda. He said, “No one else was doing it.” I didn’t see myself as brave — I saw him as brave. Yes, people questioned it all the time. But no one else was doing it. But it’s not about white guilt. It’s about pride, and if anything, it’s not really a film about race as much as it is about class in America. But if you want Americans to go crazy, tell them there’s a race problem. If you want them to go absolutely fucking apoplectic, tell them there’s a class problem.

What do you make of the criticisms over the movie’s approach to race? Some say the movie is full of stereotypes and simplifies the country’s racial tensions.

I was obviously creating a fable. That’s obvious. This was never supposed to be a realistic film. Secondly, I designed it so that for the first 20 minutes, I presented stereotypes. I did that on purpose. I did that not because I normally like to write stereotypes; I did that to say, “Okay, this is dark. You’re sitting here, and come on, we all know that Asians can’t drive, right? C’mon, relax.” [Laughs] I wanted people to relax and to say, “I’m not going to challenge you. I’m only going to reinforce every stereotype you ever thought and let you laugh at it.” And then as soon as I’ve got you relaxed, I can start twisting you around in your seat until you’re left spinning. But if I started preaching at the start, if I started even with ultra-realistic characters at the start, it wouldn’t have gotten there. I needed to service stereotypes. So when people came and said, “Oh my God, it’s a bunch of stereotypes,” I went, “Oh my God, really? You’re a fucking genius. Really? Wow, you saw that? Stunning.” Since these characters were going to meet again because that’s the nature of fables, I think they were upset also because, even though it was a fable, I had everyone dressed in regular clothing. You couldn’t obviously point to it and say, “This is a fable.” That upset people, too, and I think some people didn’t quite understand because they said it’s not realistic. Well, no kidding. I love to subvert expectations. I love to take a genre and twist it around and present it in a different way. I’m not comfortable unless I’m really nervous about how I’m telling a story in terms of structure and the way I’m doing it. That’s what “Crash” was, too. It was not an easy way to tell a story.

Would it be easier to make this movie today, when entertainment that tackles race is more prominent?

No, it gets harder and harder and harder to finance independent films. It’s harder every year. I wouldn’t bother taking “Crash” to the studios. We’ve become more and more an industry where we like safe bets. The audience likes everything underlined. We have been told to conform in the way that we tell stories. When we do that really well, we’re rewarded. And those are emotional stories and they sweep us along, and I love it. Whether it’s a comic-book film or a great drama, it has the formula. If you step outside that formula today, even more than 10 years ago, people just stare at you. Only in retrospect will they say, “Oh yes, we know that would succeed.” Even “Million Dollar Baby.” This is a movie about girl boxing and euthanasia. Take that to a studio. No. You’ll never get any money.

So the reason is because of Hollywood economics rather than the contents of the movie?

Oh, yes. Race itself would not upset them. I think we’re tackling really difficult subjects right now and doing it really well. I think it would be even easier to get a racially charged film made, as long as you’ve made it in a traditional way.

How did the cast come together?

I went through a number of casts because people signed on and then the movie kept being pushed because the financier wouldn’t finance it until it reached a certain threshold of actors. The first to come on was Don Cheadle. Since I was a nobody or a detriment as a director, we needed to get actors who other actors wanted to work with. Heath Ledger was attached at one point, John Cusack was. There were a lot of people and we just lost them because, for one reason or another, our schedule changed because we didn’t have the money together. And then finally, I think we had 10 actors. I think they allowed me to start pre-production a week at a time because we’re getting close to the date, but Bob Yari, our producer, wasn’t going to finance the film until we got more names. That was a constant struggle. Then finally Bob said, “If you get Sandy Bullock.” This was the 11th or 12th actor. I think we were supposed to be $10 million and now we were down to around $6 million or something. We had to cut down as we got more actors, but all these actors are working just for scale. Sandy read the script and said, “Yes, I want to do it.” So I called up Bob and said, “Great news, we have Sandy Bullock.” He said, “That’s great, but it’s not quite enough. If we put Brendan Fraser in, then I’ll live with it.” I went, “Brendan? Brendan’s totally wrong for this. He’s a wonderful actor, but he does comedy and he’s 20 years too young.” He said, “Yeah, but that’s what’s going to green-light your film.” So I sent the film to Brendan, he read it, he loved it, we met and he said, “Paul, I love this script, but I’m totally wrong for it. I’m 20 years too young.” I said, “I know, exactly. But we need you.” That point was two weeks before we were going to shoot. We finally got the green light and were able to start prep.

The second wave of controversy came with the Oscar race. People had — and still have — fierce opinions about whether “Crash” is worthy of its awards.

Come June or July, a few months after it had been released, the head of Lionsgate, Jon Feltheimer, and I were talking about getting the DVD released and packaged. He said, “Oh, we’re going go for an Academy Award campaign.” And I said, “Well, that’s great, because I think the actors did really, really good work.” And he said, “No, we’re going to go for Best Picture.” And I said, “Jon, please don’t. You’ll just embarrass me. It’s a small picture, an independent film. Let it live as that.” He said, “We’re going to do it.” I said, “No, I’ll be humiliated, please, please don’t.” And thank God he didn’t listen to me.

Eight months later, “Crash” won Best Picture. What was the journey to that moment?

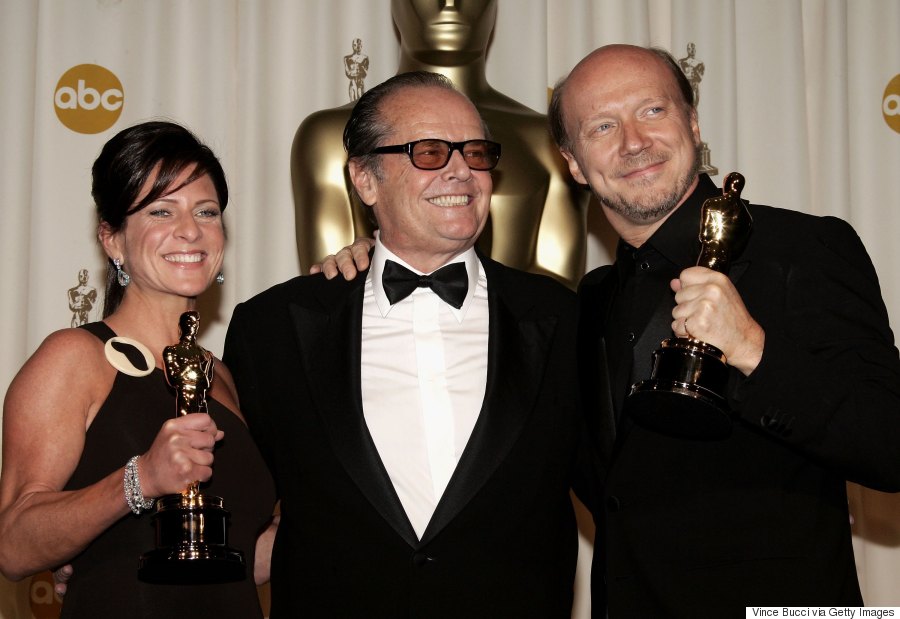

I tend to be very modest about these things, but I thought we had a really good shot at screenplay because in all the awards running up to that, we were winning for screenplay. It was never a shoo-in, but at least it wasn’t a complete surprise that we won that. Best Film? Oh please, come on. “Brokeback Mountain” had that hands down — it was winning everything all year long. We didn’t even have a shot. I did all these round tables and all these lunches and things, and at a certain point I felt like, well, I’m a Canadian and it’s really hard for me to go and tell you what a great film I have. I began to feel a little dirty. I had an excuse to go to France to do some research on something, so I took off and went to France for a few weeks right in the middle of this process. This is like the last month before the awards, and Lionsgate freaked out a little bit because this is the most important time. I said, “Yeah yeah yeah, you’ll be fine.” Then I came back a few days before the award show, and people at that time in the industry said, “You’ve got a really good shot at Best Picture.” Everybody was buzzing about this, and I said, “It’s not true. Stop it. You’re saying this because you’re my friend or you know me or whatever. We do that for friends, so bugger off.” The night of the Oscars, we won Best Screenplay, and I was thrilled. We got something for editing, and I thought, “That’s what we’re going to get.” Well, it comes to Best Picture. I’m not a fool. Ang Lee and his producers are sitting directly across the aisle from me. So as Jack Nicholson gets the envelope, I turn myself in my seat so I could face them so I can applaud. My wife is behind me, so I turn my back on her to face them because if the camera catches you, you don’t want to look like an asshole. Plus, I’m a huge fan of that movie and Ang Lee did a perfect job. He took Best Director that year over me, and he well-deserved it. And then I hear “Crash,” and I don’t quite register it. Then I feel my wife standing behind me. It’s slow-motion suddenly, and the thought goes through my head, “Does she like Ang Lee that much?” And then very quickly I stood up and realized, “Holy shit.” I was astounded. I was flabbergasted. This was never going to happen! I had no speech, I had nobody to thank, nothing in my pocket. Thank God Cathy Schulman, our producer, went up there with me and I guess she had prepared. I was stunned beyond all belief. I still am.

Are you able to look back and say that “Crash” did deserve the awards?

Oh no, I can’t say that. I mean, look at “Good Night, and Good Luck.” Amazing movie. Look at “Munich,” amazing film. Look at “Capote,” brilliant film. I’m very happy we were in that pack. But win over those pictures?

You were nominated the year before for “Million Dollar Baby,” so I assume you were an Academy member by then. Did you vote for “Crash’?

Oh, absolutely, I voted for myself. Are you crazy? [Laughs] People will often say, “Did such and such a film deserve to win an Oscar?” And I remember Jack Nicholson, someone asked him if a film — not mine, but another film — deserved to win an Oscar and he said, “Did it win? Well then, it deserved it.”

Cathy Schulman, Jack Nicholson and Paul Haggis backstage at the Oscars on March 5, 2006

With so many disparate plots, what scene stands out as the one that cements the film for you?

The first that comes to mind is that Matt Dillon/Thandie Newton car-crash scene. In that moment, I wanted to say, “What do you do to a man who thinks of himself as a hero?” And all cops think of themselves as heroes, no matter how stained they are. Deep down, they have to tell themselves that their job is to save people. What does it do to a man to look in the eyes of a woman and see that she would rather burn to death than be saved by him? And then where she realizes there’s nobody else there and she has to allow him to save her? And he treats her with such dignity in that moment, and then as they’re pulled apart at the end and Thandie Newton just walks off, she turns. The direction I gave her was to ask him who the hell he is. How can he be the person who raped her and who saved her? And she had that on her face, and Matt had it on his. Wow, that was terrific acting. Every plot line has that moment. They’re fables. That’s it.

You were a Scientologist at the time you made “Crash.” Did that influence your filmmaking?

You know, I’ve been asked that a lot, and I’ve searched to see if there was a connection. I can never find one, other than the fact that you are asked to look inward at yourself. But every religion does that. The fact that you had a faith that asked you to look inward, and I did and I found inside me all these flaws that all these characters had, so how I wrote these characters was by putting myself in their given circumstances and then writing myself. So I think that certainly helped. But that would have been the same if I’d been a Catholic.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

— This feed and its contents are the property of The Huffington Post, and use is subject to our terms. It may be used for personal consumption, but may not be distributed on a website.

This article: