In early 2014, residents in Flint, Michigan, started noticing something odd about their water. It looked different and had a foul odor. People reported problems. The state confirmed and addressed an E. coli contamination and said the water was fine, but parents were worried. Many started buying bottled water, even for cooking and showering. A Virginia Tech researcher tested the water and said it was corrosive. Finally, in September of this year, researchers confirmed Flint residents’ worst fear: lead had leached into the municipal drinking supply from old piping, and city water-lead levels were the highest they’d been in 20 years. The problem began when in April 2014 the city of Flint temporarily changed its water source from Lake …

In early 2014, residents in Flint, Michigan, started noticing something odd about their water.

It looked different and had a foul odor. People reported problems. The state confirmed and addressed an E. coli contamination and said the water was fine, but parents were worried. Many started buying bottled water, even for cooking and showering. A Virginia Tech researcher tested the water and said it was corrosive. Finally, in September of this year, researchers confirmed Flint residents’ worst fear: lead had leached into the municipal drinking supply from old piping, and city water-lead levels were the highest they’d been in 20 years.

The problem began when in April 2014 the city of Flint temporarily changed its water source from Lake Huron to the Flint River to save money. The different chemistry of the river water corroded the city’s old pipes, releasing huge amounts of lead into the drinking water.

In that time, adults and children of every age were unknowingly exposed, including formula-drinking babies and the unborn children of pregnant mothers.

Even though Flint changed its water source back after the lead was discovered, the corroded pipes have lost their protective seal, meaning the water is still unsafe and much of the system will have to be replaced. On Monday, new mayor Karen Weaver declared a state of emergency in Flint.

“We started hearing in late August of elevated water lead levels. Pediatricians freaked out,” Dr. Mona Hanna-Attisha, the director of the pediatric residency program at the Hurley Medical Center in Flint, told The Huffington Post. “That’s really when we got mobilized.”

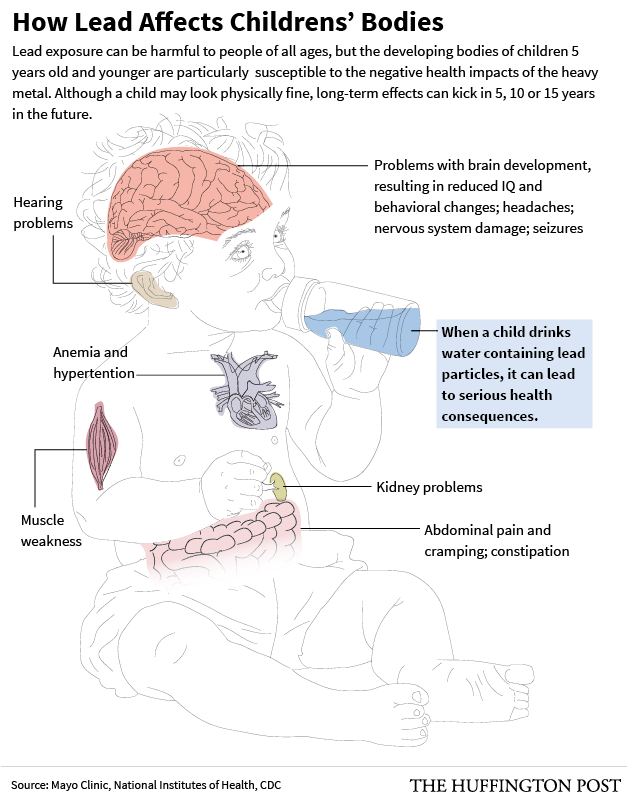

The long-term consequences of lead poisoning are dire for children, according to the World Health Organization. While a lead-poisoned infant or toddler might not show any outward physical or mental signs of damage, their developing brains are already damaged. “Your development is progressing so rapidly at those early ages,” Hanna-Attisha said. “You’re going to be carrying that exposure forever.”

Once kids reach school age, cognition problems, including lower IQ and ADHD-like symptoms start to show up. Lead exposure has been linked to physical problems, such as anemia, kidney dysfunction and high blood pressure, as well as behavioral problems, including aggressive behavior and problems with the criminal justice system.

What happened to blood-lead levels in Flint

When Hanna-Attisha heard about the Flint River’s corrosive water chemistry, she tried to get her hands on county-wide blood samples, but a county health officer told her that the data “couldn’t be easily analyzed,” according to the Detroit Free Press.

Undeterred, Hanna-Attisha turned to the Hurley Medical Center’s own records. When she compared kids’ blood-lead levels in Flint before and after the city switched its water source from Lake Huron to the Flint River, she was shocked. The number of children with elevated blood-lead levels (≥5 micrograms per deciliter) had nearly doubled in Flint. Even worse, more than 6 percent of children in zip codes with high levels of lead in the water reported these elevated levels.

Officially, more than 10 micrograms per deciliter of lead in blood constitutes lead poisoning, but increasingly, expert groups like the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention agree that there’s no safe level of lead in blood.

“We know lead and we know the life-altering, multigenerational impact of lead,” Hanna-Attisha said. “If you detect lead in a child, there’s a public health, environmental problem.”

Hanna-Attisha’s research isn’t complete, she said, because it didn’t include blood samples from infants. Lead paint is the primary source of poisoning in the U.S., where water is generally safe. Because of this, kids typically don’t get screened for lead until they turn 1 or 2, when they are more likely to be crawling around a home and putting objects in their mouths.

In the case of Flint, a city of just under 100,000 people, infants who drank powdered formula mixed with lead-tainted water and unborn babies whose mothers drank tap water are also at risk.

“Our research completely underestimated that risk,” Hanna-Attisha said. Her findings will be published in the American Journal of Public Health this month.

How Flint and other state or government agencies will ultimately respond to the situation is yet to be determined. Weaver, who was elected in November, said the city will need to increase its budgets for special education and mental health services.

“We need funding and we need resources,” she told NPR, speaking about the state of emergency. “It’s an infrastructure crisis for us, so we know that’s going to be a tremendous cost and burden on the city of Flint that we can’t handle by ourselves.”

What parents can do

While lead poisoning is essentially irreversible, there are a few steps parents can take to buffer the impact if their child has been exposed.

Removing the source of lead should be of primary concern, but nutrition is important, too. Children who are iron-deficient or have empty stomachs absorb lead more easily, which puts low-income kids, who can’t control their housing stock and are more likely to be poorly nourished, at the highest risk, Hanna-Attisha explained. Parents who think their kids have been exposed should see their doctor. The sooner experts can pick up on a developmental delay, the better the child’s long-term outcomes will be.

“Our community has been traumatized,” Hanna-Attisha said. Still, she cautioned that city residents shouldn’t panic. “This terrible thing happened, but it doesn’t mean every kid is going to have all these problems,” she added.

“If we can advocate in a state of emergency, and in the future for additional resources, great schools, parenting programs, great nutrition and access to foods, hopefully we don’t have to see the full impact of this exposure.”

Listen to HuffPost Politics’ interview with Hanna-Attisha below:

Also on HuffPost:

— This feed and its contents are the property of The Huffington Post, and use is subject to our terms. It may be used for personal consumption, but may not be distributed on a website.

View the original here:

Why Pediatricians Are So Alarmed By The Lead In Flint’s Water