“I think for Trenton, being black and being male, to be an artist is sort of an anomaly for him,” explained Valerie Cassel Oliver, senior curator at New York City’s Studio Museum. She’s speaking about Trenton Doyle Hancock, the artist at the center of “Trenton Doyle Hancock: Skin and Bones, 20 Years of Drawing,” now on view in Harlem. “People like him often expect to be incarcerated. He realized that being a black man and being an artist is a rarity, it’s a gift, because he was supposed to be something completely different. Understanding those injustices exist make him want to talk …

“I think for Trenton, being black and being male, to be an artist is sort of an anomaly for him,” explained Valerie Cassel Oliver, senior curator at New York City’s Studio Museum.

She’s speaking about Trenton Doyle Hancock, the artist at the center of “Trenton Doyle Hancock: Skin and Bones, 20 Years of Drawing,” now on view in Harlem.

“People like him often expect to be incarcerated. He realized that being a black man and being an artist is a rarity, it’s a gift, because he was supposed to be something completely different. Understanding those injustices exist make him want to talk about it … to bring it more or less to questions about morality,” Oliver told The Huffington Post. “Often times morality is not simply black or white. I think his visual mythology gets to that.”

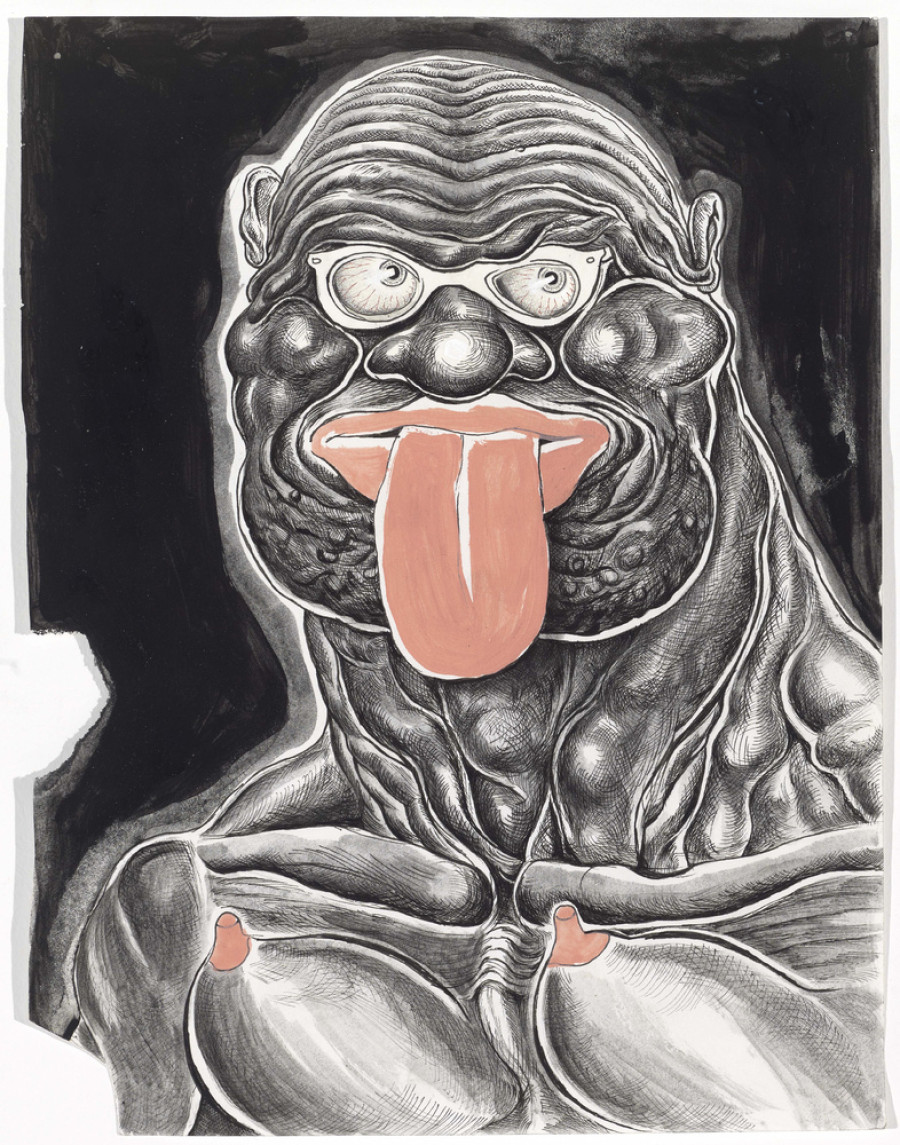

Hancock was born in 1974 in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, and raised in Paris, Texas. He left the rural town to study art at East Texas University and Philadelphia’s Tyler School of Art. Here, his Southern, religious upbringing mingled and merged with other, far more grisly, influences, including graphic novels, cartoons, music and film.

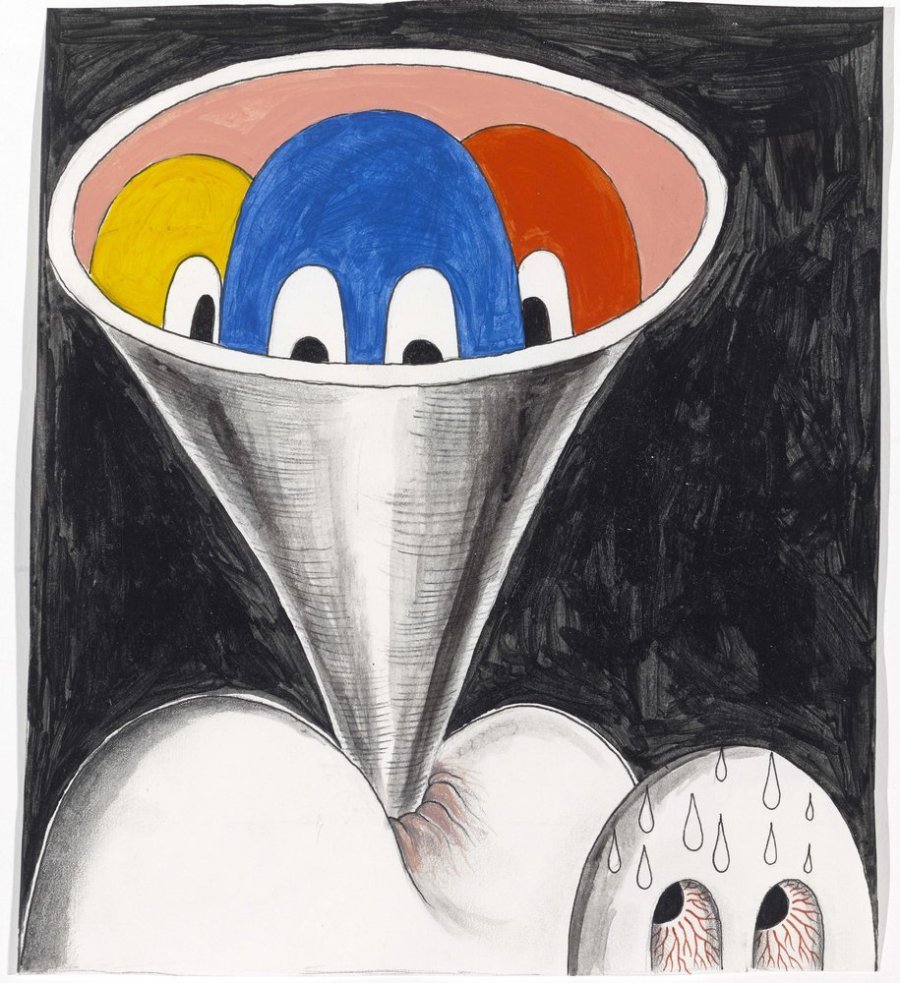

“He was definitely influenced by comic books and later underground comic books,” said Oliver. “Things like [Robert] Crumb and also things that are more highbrow, like folk art. There are a lot of influences that go into Trenton’s visual language. It goes from a punk aesthetic to a Renaissance aesthetic. He has a profound love of toys as well — playing cards, The Garbage Pail Kids, the old Godzilla figures. He truly does drink in everything.”

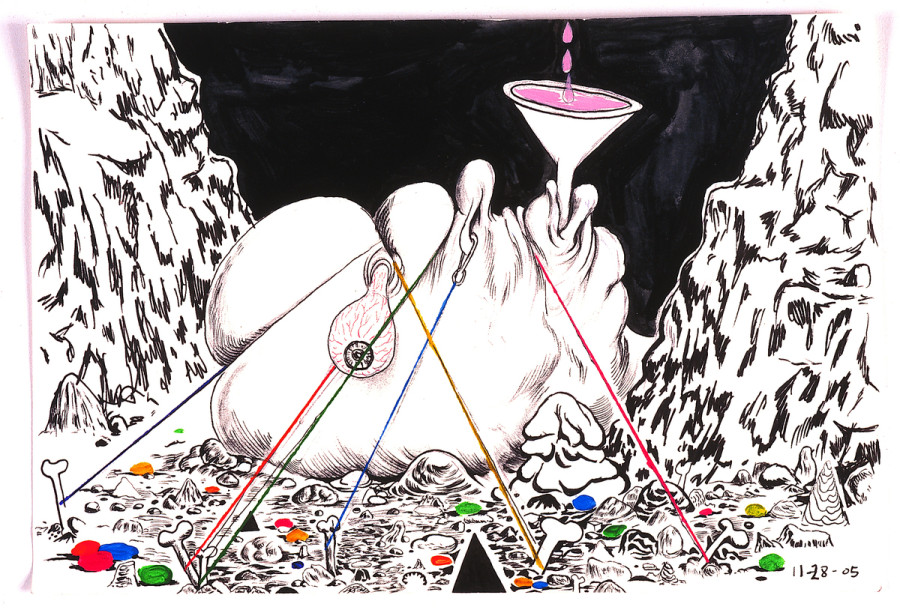

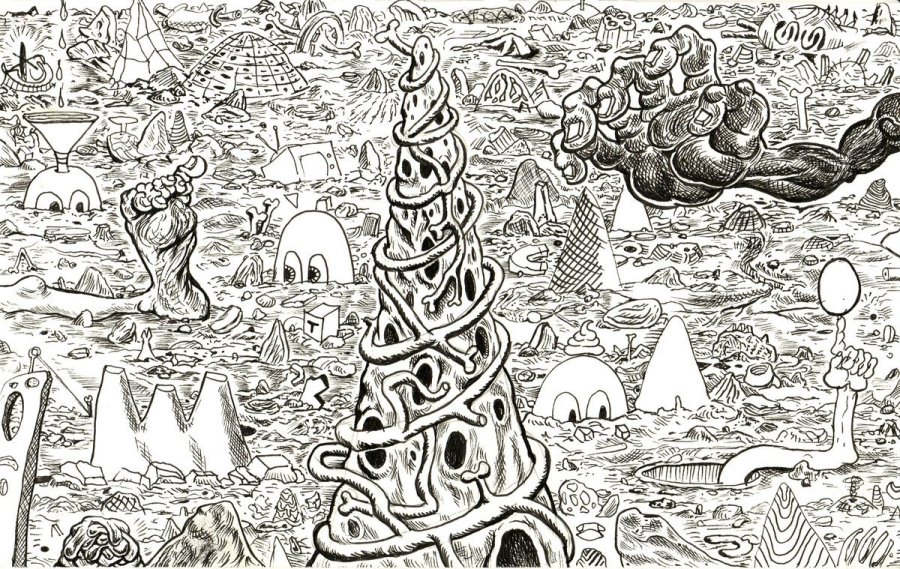

Looking at Hancock’s artworks, his hoarder aesthetic is more than obvious. Traces of Peter Saul, Kenny Scharf and Gary Panter fight for room on the clustered surfaces, teeming with squiggly torsos, bulging, bloodshot eyeballs, spindly legs and bubble butts. If a (wildly talented) stoned teenage boy had his way with Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel ceiling, it may resemble Hancock’s chockablock creations.

Despite all the elements of wild fantasy at play (and war) in Hancock’s work, they’re not as removed from this world as it may initially seem. “There are these questions about a moral compass, done in a way that’s very accessible,” Oliver explained. “It’s not dogmatic; it doesn’t point to one thing or another. But rather, it allows people to examine it from afar and then coming full circle and letting people adjust their own internal compass.”

Viewers can apply this moral compass to whatever issues take the foreground in their lives. For Hancock, as a black man in America, it often comes back to race.

A closer look at Hancock’s work illuminates the many ways race and racism enter the convoluted mythology. Cartoonish Klansmen are one of his most recurring symbols — an allusion to a lynching that occurred in 1893 in his hometown of Paris. Artnet News points out Hancock’s use of striped fur on his famous “Mound” creatures, evoking “old-timey convict uniforms, insinuating consciousness about the targeting of black men by the criminal justice system.”

Hancock is most well known for his absurd and monumental narrative, an epic chronicling a battle between the Mounds and the Vegans — which, yes, are based off those who adhere to a strictly vegan diet.

“Mounds are these half-human, half-plant mutants that came to life about 50,000 years ago,” Hancock explained to Art21, “when an ape-man masturbated in a field of flowers, and up sprang these creatures, and they’re called Mounds. Since then, many of them have died off for various reasons, but the main cause of death of Mounds is the premature death caused by creatures called Vegans who are evil creatures who can’t stand Mounds at all.”

For Oliver, it was Hancock’s “expansive mythology” which initially caught her attention. “There was a sincerity in it,” she explained. “It struck me as something you would hear from what I call a visionary artist, what some people refer to as a self-taught artist, although he’s not self-taught. But nonetheless, he embodied that drive and passion in terms of direction that one would hear from a visionary artist in the intensity of his canvasses.”

The extensive undertaking is reminiscent of outsider artist Henry Darger, creator of the longest work of fiction of all time — the 15,000 page illustrated epic titled The Story of the Vivian Girls, in What Is Known as the Realms of the Unreal, of the Glandeco-Angelinian War Storm Caused by the Child Slave Rebellion. The tale tells the story of conflict on an imaginary planet between the evil Glandelinians and the Catholic Abbieannians, a turbulent war between virtue and wickedness, innocence and perversion. It’s one of the more bizarre treatises on good and evil out there, opting for an absurd fable over a preachy sermon. Hancock’s Mounds and Vegans, although far less of a mouthful, embark on a similar moral quest.

While Darger attended church five times a day throughout most of his life, Hancock too had an unusually charged relationship to religion. His stepfather is a Baptist minister, preachers run in the family, and most of his family grew up “very, very religious.” The archetypal Biblical story of the hero overcoming struggles, as well as the traditional notions of capital “P” punishment, spilled into Hancock’s notion of building a narrative trajectory.

Just as many of Hancock’s tripped out imagery has roots in the real world, so his inexhaustible layers of influences, symbols, squiggles and folds mimic the complexity of the historicized present. For example, when Hancock was awarded the NAACP award in Paris, Texas, his grandmother, who introduced the prize, gave an introduction which included information about the dark histories of landmarks sprinkled throughout the town.

“Hancock could not understand the history and the gravity of these landmarks,” Oliver explained. “Hearing his grandmother, his mother, his aunt, talk about having different experiences with the different generations there, he realized there was this history of Paris that involved lynching. The Paris Fairgrounds he would go play on as a kid — his grandmother couldn’t even get near there. There was this moment about understanding the various intersections of history, and Trenton was bringing all of these divergent, seemingly unrelated histories together in one place.”

Hancock’s images are wildly intricate to be sure, but no more so than the historical layers of the world around us. He depicts the tangled terrain where past battles with present, good grapples with evil, with all the grotesque details lurking at every corner. Like Darger, Hancock’s works are visionary, opening up a hole into another world all his own, filled with melting bunnies and demonic skeletons. And yet, they’re never too far from the troubles on this planet, in this country, right now.

Trenton Doyle Hancock “Skin and Bones, 20 Years of Drawing” runs from March 26 until June 28, 2015, at the Studio Museum in New York City. Valerie Cassel Oliver originally curated the show for the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston in 2014.

— This feed and its contents are the property of The Huffington Post, and use is subject to our terms. It may be used for personal consumption, but may not be distributed on a website.

More –

Trenton Doyle Hancock’s Drawings Confront The State Of Racism In America Today