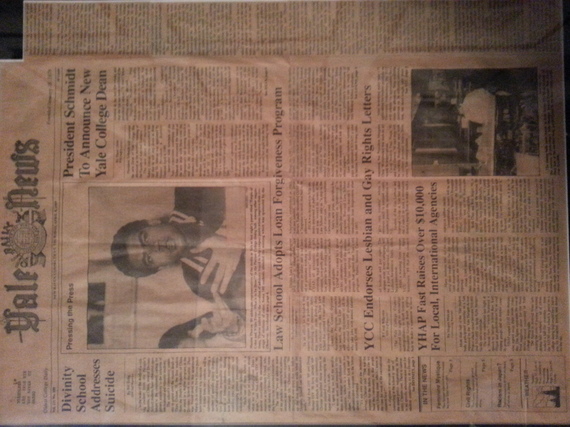

For those of us involved in social movements we get that our life’s work is to educate the majority. For many of us, that began in school. The conversations and eruptions taking place on Yale’s campus are not new. When I was a student at Yale in the 1980s and 1990s I participated in similar disruptions. I made the front page of the Yale Daily News in 1988 in a story that is reminiscent of the ones today. Friends decades before did the same. That we all paid different personal, career and other significant costs cannot be overstated. But Yale, American society and the world changed. Meeting Blacks where you shop and…

For those of us involved in social movements we get that our life’s work is to educate the majority. For many of us, that began in school. The conversations and eruptions taking place on Yale’s campus are not new. When I was a student at Yale in the 1980s and 1990s I participated in similar disruptions. I made the front page of the Yale Daily News in 1988 in a story that is reminiscent of the ones today. Friends decades before did the same. That we all paid different personal, career and other significant costs cannot be overstated. But Yale, American society and the world changed. Meeting Blacks where you shop and work, attend school or church or hang out changes how Whites perceive them: the “you are different” trope.

The chance to educate, while experienced differently for Whites and Blacks, should not be undervalued either. This is particularly true at Yale and centers of power. The interpersonal and interfamilial even in the horrors of slavery could change outcomes. You can contrast the loathsome behavior of Thomas Jefferson against that of Lord Chief Justice William Murray (Earl of Mansfield). His niece, Dido Elizabeth Belle, born a biracial slave in Barbados, was brought to live with him in England. Her impact on him resulted in the first (and outlier) decision which held that the common law in England and Wales could not condone slavery. Humans are odd creatures: we often respond less to ideas than personal contact, less to theories than personal anecdotes.

Why did the gay rights moment adopt the strategy of coming out “where you pay, pray or play”? Even when coming out could cost you your job, family or friends (or even life)? LGBT people were implored to “come out” to educate those around them.

Because knowing someone who is gay or lesbian affects views on gay issues. Gallop polling in 2009 showed that among those who do not personally know anyone who is gay, 72% oppose legalized gay marriage while just 27% favor it. Americans who personally know someone who is gay or lesbian are almost evenly divided on the matter, with 49% in favor and 47% opposed. The statistics are even more promising for students who are school and college age. Growing up with “out” kids has transformed how generations of young people now regard gay and lesbians and marriage equality.

The gay rights and marriage movement learned a lot from the civil rights movement for racial justice.

Most Americans are proud of the progress on racial justice. Obama’s Presidency is just one achievement in the arc of justice for Black people across the globe, not just for African Americans. Western Europe and the Americas share a history of enslaving and oppressing Africans, transporting them across the globe to became labor and the bedrock for their economies.

The transformation from those slave societies to the democracies in which we now live is ongoing. Much of the struggle for acceptance, equality and happiness have fallen on young people: Black, White, majority and minority youth. When slaves revolted, when free people sought to be educated, when the educated sought to get work, when workers sought for equal pay, promotion, and more: the burden fell on the shoulders of young people. Young minorities and their allies.

In a seminar on Philanthropy that I taught at Yale, students explored the private philanthropic underpinning of American social movements and education. They were often surprised at how unscientific, religious and racist educational institutions were and the private wealth it took to create and transform them. Julius Rosenwald (Sears, Roebuck & Company), John D. Rockefeller (Standard Oil Company) and Andrew Carnegie (Carnegie Steel Corporation), for example, used their great wealth to liberate education from the stranglehold of religion and “Whites only” ideologies. Today we have NJSeeds, the Walton (Walmart) Family Foundation, the Broad Foundation, the Bill and Melinda Gates (Microsoft) Foundation, and the Dell (Computers) Foundation and Hedge Fund tycoons like Daniel Loeb of Third Point, Paul Singer of Elliott Management, Paul Tudor Jones of Tudor Investment, and John Paulson of Paulson & Co. all supporting in one guise or another educational access for Blacks.

However, the South resisted this Northern alliance of wealth and educational reform. Even though Rockefeller founded Spellman and Morehouse colleges for Blacks and Rosenwald founded over 5,000 schools for Black children, the predominant theory philanthropists (and goverment) implemented meant educating White Southerners first. UVA President Edwin Alderman reasoned that education for Whites would make them more tolerant of Blacks.

Horace Mann Bond, who became the first Black President of Lincoln University, noted when he was doctoral student for the Rosenwald Fund that the pursuit of Black educational opportunity was carried out under constant threat of White violence with a fear that funding might take “the Negro beyond himself.” His wife Julia thought the Black community was “at the mercy of whatever impulse may come over these White people.” His son 17 year old son Julian was a founder of SNCC who helped orchestrate the civil rights movement.

A 2011 HBS article by Michael I. Norton and Samuel R. Sommers should inform our thinking about lingering problems on college campuses and elsewhere. They note several legal and social controversies regarding ”reverse racism” that highlight Whites’ increasing concern about anti-White bias.

“We show that this emerging belief reflects Whites’ view of racism as a zero-sum game, such that decreases in perceived bias against Blacks over the past six decades are associated with increases in perceived bias against Whites–a relationship not observed in Blacks’ perceptions. Moreover, these changes in Whites’ conceptions of racism are extreme enough that Whites have now come to view anti-White bias as a bigger societal problem than anti-Black bias.”

Perhaps this helps explain how “Black Lives Matter” is heard by some as “White Lives Don’t Matter.” Their data demonstrate that not only do Whites think more progress has been made toward equality than do Blacks, but Whites also now believe that this progress is linked to a new inequality–at their expense.

The burden on Black students at Yale isn’t fair. And certainly not when taken in isolation if getting a degree in maths, for example, is your end goal.

But we continue to live in some horrific national and global times where students receive death threats. At the University of Missouri, Hunter M. Park and multiple others made online line death threats against the black football players who called successfully for the resignation of the President. The students were protesting the way the University handled complaints against racism.

As in Missouri, Black students’ impact can be exponential on the university and society, if only because we live in a world of such inequality and disparity in access to justice, credit and power.

They can control their own bodies and refuse to play ball, and influence and curate relationships that can impact lives around the world, now and in the future. And they should.

Of course, Missouri, Yale and their communities owe a duty to all its students, and its Black ones. Yale did so when sending out the “Halloween email” from The Intercultural Affairs Committee – asking students “to avoid those circumstances that threaten our sense of community or disrespects, alienates or ridicules segments of our population based on race, nationality, religious belief or gender expression.”

What has erupted proves the case of the continued need to build cultural competencies across Yale and indeed across all campuses and communities.

We (and black and white students) don’t have to, don’t warrant this. But should we all not embrace that awesome challenge we may forfeit the future that is ours to own and make better.

Please tweet me @maximthorne or email maxim@maximthorne.com

— This feed and its contents are the property of The Huffington Post, and use is subject to our terms. It may be used for personal consumption, but may not be distributed on a website.

Read this article:

Transforming the Majority Shouldn’t be the ‘Job’ of Minorities, But it Is. Especially for Students.