The state has no power more awesome than its capacity to take the lives of its citizens. In recent decades there has been growing public unease with this capacity, and a powerful moral, legal, and political assault has resulted in the abolition of capital punishment in every wealthy democratic country except the United States and Japan. Even in the United States, still one of the world’s 10 leading users of the death penalty, the practice of capital punishment has been sharply circumscribed, with elaborate trials, guaranteed and publicly subsidized legal defense, and multiple opportunities to appeal. As a result, the actual employment of capital punishment has dropped sharply, falling from …

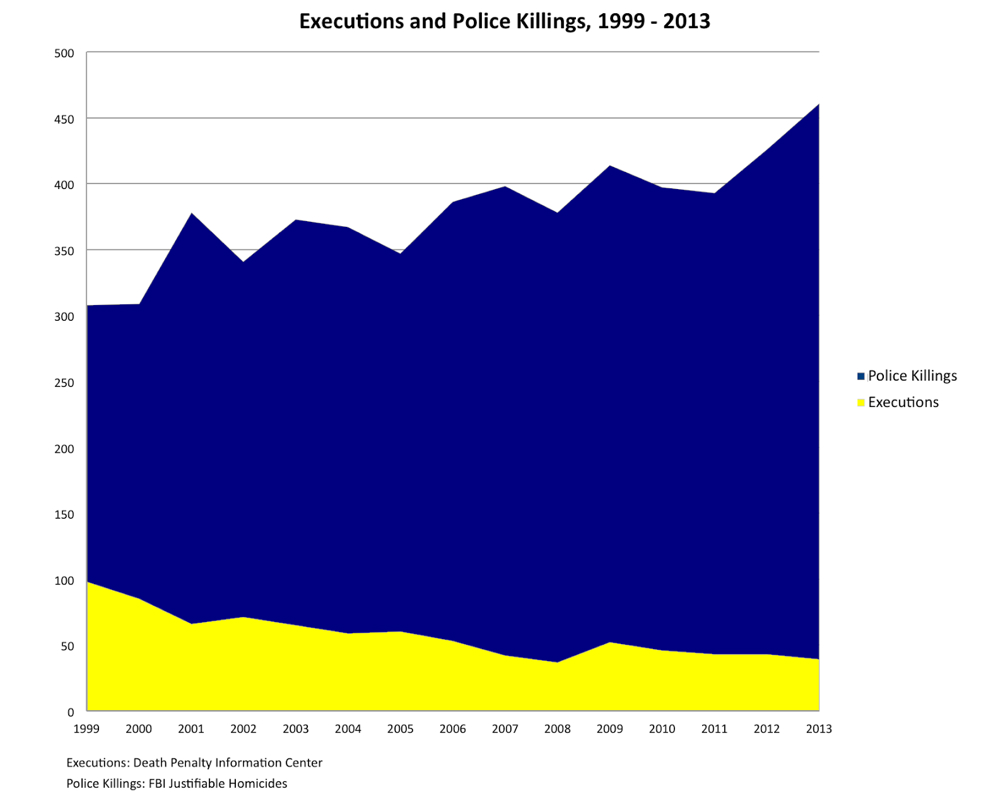

The state has no power more awesome than its capacity to take the lives of its citizens. In recent decades there has been growing public unease with this capacity, and a powerful moral, legal, and political assault has resulted in the abolition of capital punishment in every wealthy democratic country except the United States and Japan. Even in the United States, still one of the world’s 10 leading users of the death penalty, the practice of capital punishment has been sharply circumscribed, with elaborate trials, guaranteed and publicly subsidized legal defense, and multiple opportunities to appeal. As a result, the actual employment of capital punishment has dropped sharply, falling from an average of 77 per year between 1999 and 2003 to 49 a year between 2009 and 2013 — a far cry from the 180 per year in the mid-1930s, when the United States was well under half as populous as it is today.

Yet if traditional capital punishment — defined as the state’s execution of a human being for the commission of a crime, real or alleged — has declined, another kind of capital punishment continues unabated. This other form of capital punishment, far more common than the traditional kind, involves the killing of Americans by the police without benefit of charges, trial, jury, or the right to appeal. The much-publicized cases of Michael Brown, Eric Garner, and Tamir Rice are examples.

Because there is no mandatory reporting of police killings and hence no comprehensive statistics, it is impossible to know how many such killings take place each year. But what is certain is that this other, less visible form of capital punishment dwarfs the traditional kind; by an extremely conservative estimate, it is nearly 10 times as frequent as the executions reported each year by the Death Penalty Information Center.

Click to enlarge

The most conservative estimate of the number of police killings comes from the FBI’s “Uniform Crime Report.” Based on data only from those jurisdictions that voluntarily provide it to the FBI, the report finds that an average of 418 people per year were killed by the police in the last five years, with the number reaching a 20-year high of 461 in 2013. But these figures, as The Wall Street Journal has demonstrated in a careful study of 105 of the nation’s largest police agencies (35 of which did not appear in the FBI records), reveal over 550 police killings in the 2007-2012 period that were not reported in the FBI tallies, suggesting that the FBI figure underestimates the number of actual police killings by roughly 45 percent. Other informed estimates are even higher; a recent piece on FiveThirtyEight based on an analysis of the Facebook page “Killed by Police” suggests that the correct figure may be about 1,000 deaths per year at the hands of the police. But whether the number is 450 or 1,000, this constitutes a form of spontaneous and unaccountable capital punishment that is 10 to 20 times greater than the traditional type of capital punishment that has been subjected to years of careful public scrutiny.

This level of police violence in the United States is an extraordinary aberration among wealthy democratic countries. In Germany in 2011, there were six police killings; in England in 2013, there were none. To be sure, the United States is a much more violent society than Germany and England; in 2013 the American murder rate was five to six times higher. But this disparity hardly explains a rate of killings that The Economist estimates is 100 times greater than in Britain.

Many Americans accept and rationalize police killings as the cost of maintaining order in a violent and disorderly society. In this context police violence — like the broader culture of violence of which it is a part — has come to be taken for granted. With very few exceptions police in the United States kill with impunity. A recent study of 179 killings by New York City police between 1999 and 2013 reported just three indictments and only one conviction, with no jail sentence.

But other societies are not so accepting of killings by the police. In 2011 a police shooting of a known gangster provoked riots across London and led to a fiercely debated inquest. And a 2005 killing of an innocent Brazilian in the wake of the July terror bombings seriously tarnished the reputation of the London police.

The bond of trust between the police in America and the communities they serve, never strong in minority neighborhoods, is now seriously frayed. Yet the problem of police violence is an American problem, not just a racial problem. Undeniably, blacks are disproportionately the victims of police violence; in a widely publicized study of seven years of police killings reported in the FBI data base, USA Today found that white officers killed a black person an average of 96 times a year. Not emphasized, however, was an equally striking finding: that three quarters of police killings fell outside the familiar pattern of white officer, black victim.

Can anything be done to control the other capital punishment: the wave of police killings that vastly exceeds traditional capital punishment? Effective action will require a forthright acknowledgment of the sheer magnitude of the problem and a firm public conviction that hundreds of human beings killed by the police each year is neither necessary nor inevitable. Four specific measures would begin to address the problem:

- Thorough investigation of every police killing by an outside and independent body, which would then be required to issue an official report on the findings of its investigation. A landmark piece of legislation doing exactly this was signed into law in the spring of this year by Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker, a Republican, suggesting that such legislation would have bipartisan support. The origin of the legislation, which was modeled on the approach that the military takes to investigations of plane crashes, was a relentless campaign by retired Air Force Lt. Col. Michael Bell, whose son, as he put it, was a “blond-haired, blue-eyed boy who was shot in the head while his hands were behind his back in handcuffs, being held down by another officer,” according to five eyewitnesses. Mr. Bell reports that he was unable to find a single case of a police shooting deemed “unjustified” in the 129 years since police departments in Wisconsin were founded in 1885.

- Mandatory reporting by local and state police of every police killing to the Department of Justice and the FBI. Comprehensive and uniform data, including the age, gender, and race of the victims and the officers involved, should be included in the FBI’s “Uniform Crime Report.” Such reporting, which should include an account of the precise circumstances surrounding the death, will bring to an end the remarkable situation in which we do not even know how many Americans are killed by the police each year.

- Systematic and carefully evaluated experiments with police body cameras at both the state and local level. Body cameras are by no means a panacea, but they should add to the evidentiary record available in investigations of police killing and may exert a deterrent effect on excessive police force. Though the results of limited recent experiments with police body cameras in Rialto, California; Mesa, Arizona; and other communities are less than definitive, the use of body cameras would begin to address the public’s sense that police practices are lacking in both transparency and accountability.

- Thorough reform of police training, with special emphasis on the mastery of techniques designed to minimize the use of force. German police training, which takes up to three years, involves repetitive practices on how to remain calm while handling volatile situations. But reformed training of the police must involve more than the teaching of better technique; a police culture that promotes excessive reliance on weaponry must also be changed. A recent report by the Justice Department on the Cleveland police underlines the depth of the problem. The report detailed instances of police “firing their guns at people who do not pose an immediate threat of death or serious bodily injury” and concluded that “Cleveland police officers violate basic constitutional precepts in their use of deadly and less lethal force….”

Reducing police killings will not be an easy matter. Being a police officer in America is a difficult and dangerous job, and the police face a citizenry far more armed than in other countries. More than any other advanced nation, America is a gun culture, and criminals and police alike are embedded in this culture. But even in a country where gun ownership is widespread and levels of homicidal violence are high, the annual spectacle of hundreds of people being shot and killed by the police is intolerable. Another way is possible, and the growing public outcry against police killings visible across the country is a signal that the time to address the other capital punishment is now.

Original link: