William English Walling and Anna Strunsky It was late-summer 1908 in Springfield, Illinois, 43 years after the assassination of its most famous resident, Abe Lincoln. It was a place where a person could live and work among the sun-toasted plains, the sparkling clear creeks, and the strong-wooded trees that had learned to survive the worst Midwest storms. But terrible storms are manmade, too. That August, a savage mob of white residents enraged over reports of a black man sexually assaulting a white woman, launched a three-day war against the city’s black residents. Homes and businesses were burned to the ground. Black people were lynched, beaten, berated, and exiled. Terrified for…

It was late-summer 1908 in Springfield, Illinois, 43 years after the assassination of its most famous resident, Abe Lincoln. It was a place where a person could live and work among the sun-toasted plains, the sparkling clear creeks, and the strong-wooded trees that had learned to survive the worst Midwest storms.

But terrible storms are manmade, too. That August, a savage mob of white residents enraged over reports of a black man sexually assaulting a white woman, launched a three-day war against the city’s black residents. Homes and businesses were burned to the ground. Black people were lynched, beaten, berated, and exiled. Terrified for their lives, many black families fled the city. At least six people died.

Community and state leaders — including the governor — stayed silent, or worse, defended the riots. Even the local newspapers reported the savagery with an almost zealous tone, condoning the actions of the white mob against its fellow black residents. But William English Walling, known to friends and family as “English,” a journalist-activist, labor reformer, and the son of a former slave owner, wasn’t one of them.

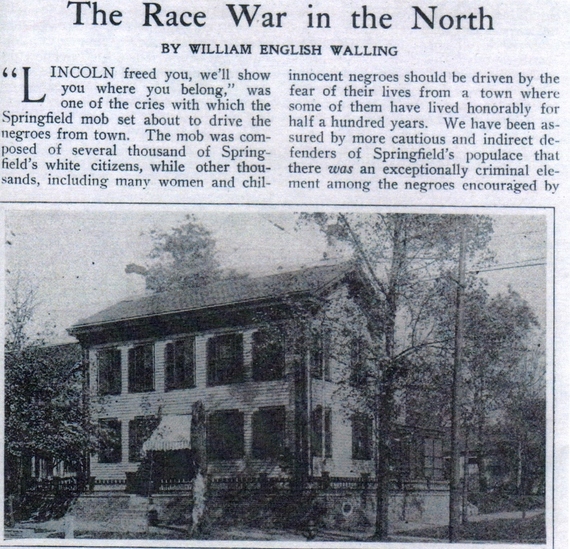

Exposing the brutality, on September 3, 1908, he published an article, “The Race War in the North,” for The Independent, a weekly magazine with an abolitionist heritage. English’s story was a cry for public decency, for true democracy, and a wake-up call for the entire nation. In the tradition of investigative, watchdog journalism, that particular news story has since been credited for lighting the fuse that led to the creation of the national civil rights organization known today as the NAACP (the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People).

Before I go any further, however, it’s only fair to tell you that my reverence for this historical story isn’t solely a modern-day reflection on a crucial civil rights milestone. For me, it seeps far deeper than that because English was my great uncle as well as my middle namesake. I feel compelled to tell this story because, over the years, it’s been forgotten, fading into the background as time –contrary to the essence of this affliction — moves on.

And, as with most events, there’s more to the story.

So how did English end up in Springfield in the midst of those murderous riots? Because his wife, Anna Strunsky — a journalist, a writer, a former Russian dissident prisoner, a relentless social activist and the only person to ever coauthor a book with Jack London — insisted that they both catch the next train out of Chicago to cover the Springfield riots in person.

Anna wasn’t new to high-profile social or political controversy; in fact, two years prior she’d made the front page of the Chicago Daily News for refusing to take her husband’s last name. The headline declared, “In Defiance of Social Conventions; As Anna Strunsky She Will be Known.” Before the Springfield race riots, both Anna and English had been well recognized for their writings on a variety of causes including labor rights, disenfranchisement, and the 1905 Russian Revolution. English’s goal in traveling to Springfield was, in his words, “to write a broad, sympathetic and nonpartisan account.” But once he saw the carnage and tensions, he quickly switched gears.

In his article, English assessed the Springfield riots as being of particular symbolic importance because they were happening in the hometown of Abraham Lincoln, our nation’s “Great Emancipator.”

Further, English felt that the “fanatical, blind and almost insane hatred of the black community by the white citizens of the north had initiated a permanent warfare.” English derided the local press for inflaming public opinion against the black community by holding an entire race responsible for the actions of a handful of criminals and perniciously stirring the passions of the racist component of the white community.

Then English turned to what he believed was an even greater danger of the Springfield riots: He pointed out that because the town’s black population was relatively small (roughly 6.5 percent), it “could not possibly endanger the ‘supremacy’ of the whites.” Therefore, the true motivation of the rioters was purely economic — in other words, it was about taking over the jobs, property, and businesses of the black community. “[E]very community indulging in an outburst of race hatred will be assured of a great and certain financial reward,” he wrote, “and all the lies, ignorance and brutality on which race hatred is based will spread over the land.”

Extrapolating his theory of economic motivation, English broadly framed the events in Springfield as a dark symbol of the growing threat to America’s democratic principles:

The day these methods become general in the North, every hope of political democracy will be dead, other weaker races and classes will be persecuted in the North as well as the South, public education will undergo an eclipse, and American civilization will await either a rapid degeneration or another profounder and more revolutionary civil war, which shall obliterate not only the remains of slavery but all the obstacles to a free democratic evolution that has grown up in its wake.

The last line of English’s article was a clarion call to create a national organization for civil rights: “Yet who realized the seriousness of the situation, and what large and powerful body of citizens is ready to come to their aid?” His plea was immediately taken up by Mary White Ovington, a well-known social rights journalist for the New York Evening Post, herself a descendant of an abolitionist and ardent civil rights proponent.

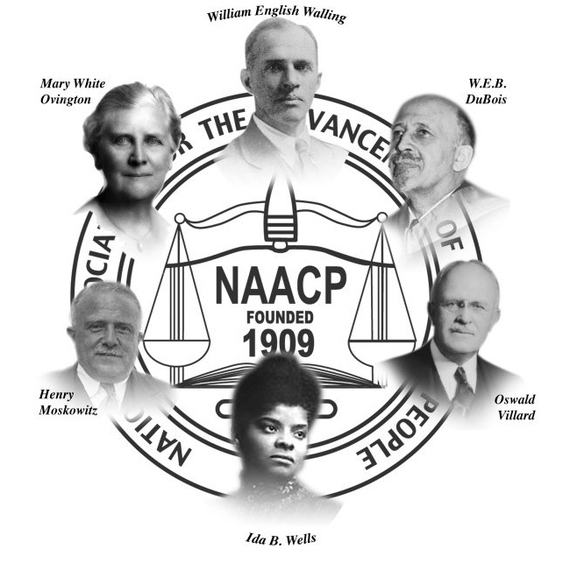

According to NAACP records, after reading English’s article, Ovington arranged a meeting between herself, English, and social worker Henry Moskowitz. The three met in English and Anna’s apartment on West Thirty-Eighth Street, New York City. There they began planning a national civil rights organization, issuing a call for a national conference on the civil and political rights of black Americans.

From May 31 to June 1, 1909, the temporary National Negro Committee held its first meeting in New York City, and in May 1910, English became the chairman of the NAACP’s executive committee. The original founders of the NAACP were English, Moskowitz, Ovington, civil rights icon W.E.B. DuBois, journalist and suffragist Ida B. Wells, and journalist and Nation Magazine editor Oswald Garrison Villard.

In his extensive book, NAACP: A History of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, Charles Flint Kellogg found that nothing else had “resulted in any definite action to combat the rising tide of racism.” He continued: “That stimulus was provided by William English Walling in his article.” Although buried deep in the record, most historians and biographers agree that it was English’s article that galvanized the group that formed the most prolific civil rights organization in American history.

But you may still wonder why English’s call to arms — especially from a white man from Kentucky and son of a former slave owner — became the catalyst for rallying US citizens to form a national civil rights group to advocate for black citizens. James Boylan, author of Revolutionary Lives: Anna Strunsky and William English Walling, characterizes English’s position as, “[f]ar beyond what even enlightened opinion was ready to support.”

So although his position was radical for his time, it was palatable to many in the movement because of the profound eloquence and daring that it encapsulated. It also helped, as Boylan highlights, that English was a “kind of spiritual counterpart” to black leader W.E.B. DuBois, famed author and civil rights crusader. In fact, English actively recruited DuBois to the NAACP as its first director of public relations. The two men shared similar philosophies about the civil rights movement — mainly a broader societal realignment than other activists of that time, particularly esteemed black leader Booker T. Washington, who advocated that blacks should operate within the confines of Jim Crow discrimination laws and policies. DuBois so famously challenged Washington by writing, “In all things purely social we can be as separate as the five fingers, and yet one as the hand in all things essential to mutual progress.”

I believe my great-uncle’s story resonated so strongly more than a century ago because English fully understood what many still don’t today — that racial injustice, social marginalization, and severe economic inequality are among the most serious threats to American democracy. His early and uncompromising realization of this fundamental truth gives me tremendous pride in carrying his name.

View original article: