[ad_1]

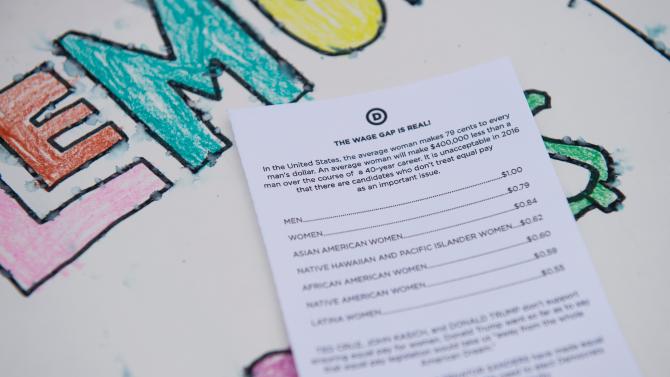

Democratic National Committee women host an Equal Pay Day event with a lemonade stand “where women pay 79 cents per cup and men pay $1 per cup, to highlight the wage gap,” on April 12, 2016, in Washington, D.C.

MOLLY RILEY/AFP/Getty Images

“Lots of people have heard the 79 cents on a dollar that women make on average compared to men,” says Emily Martin of the National Women’s Law Center. But the level of salary loss for a woman starting her career today is staggering. “Nationally, a woman stands to lose about $430,000 over a 40-year career if we don’t take action to close the wage gap.”

An analysis by the Washington, D.C.-based nonprofit advocacy group shows that the numbers for women of color are even more egregious in comparison with the salaries of white, non-Hispanic men. For African-American women, the lifetime wage gap is $877,480. For Latina women, the gap is more than $1 million. NWLC, using numbers from the U.S. Census Bureau, did an interactive map with state-by-state rankings. The largest gap, for both black and Latina women, is in the nation’s capital.

“For Latinas,” says Martin, NWLC’s general counsel and vice president for workplace justice, “it’s $1.8 million. For African-American women, it’s about $1.6 million.”

The study found that the widest lifetime wage gap for Asian-American women is in Alaska, where the spread is $1.2 million. The gap is over $1 million for African-American women in six states, including Louisiana. It’s more than $1 million for Native American women in 13 states, including California; for Latinas, it’s more than $1 million in 23 states, including New York and Texas. Why is the gap so large for women of color?

“For Latinas in particular, likely a primary reason for this is occupational segregation,” Martin explains. “Latinas are very overrepresented in a lot of low-wage jobs—for example, cleaning jobs. Latinas are 6.6 percent of the workforce overall, for example, but 15 percent of the low-wage workforce. On the other hand, Latinas are much underrepresented in the highest-paying jobs in the economy—for example, executives, attorneys, surgeons and engineers.”

She adds that white men are very overrepresented in high-paying jobs. Other causes for the wage gap are basic, such as the fact that women are still being paid less for doing the same work.

“When you see studies that control for all the things that should affect someone’s pay, like experience and how many hours they work and their education, there’s still a wage gap between men and women that is not explained,” Martin says. “Another cause of the gap is when women are parents or have other caregiving responsibilities. Often their income takes a hit … because their working conditions don’t allow them to succeed at work in the same way once they have caregiving responsibilities.”

One can see this on a daily basis in the restaurant industry, says Gaby Madriz, director of the Restaurant Opportunities Center United in Washington, D.C., and a former restaurant worker. Part of the reason for that, she says, is racism, citing a report issued by her nonprofit advocacy group.

“There’s a drastic lightening in shades when you go from the lowest-paying jobs to the highest-paying jobs,” Madriz explains. “The folks in the back of the house doing the cooking and the prep and the line cooks tend to be black and Latino folks, a lot of immigrants. … The chefs and the sous chefs tend to be white males.”

The optics are even clearer, she says, once you get to the front of the house.

[ad_2]