We are three young people working with the Democratic Movement (MoDem) in the Seine-Saint-Denis neighborhood. We are writing to share our experiences 10 years after the riots rocked all of France, not just our neighborhood. Our goal is to assess the changes that have unfolded over the past 10 years, and, above all, reflect on what remains to be done in areas that have been referred to as “priority neighborhoods.” Fadhil, 22 I was 12 years-old when the riots broke out in 2005. They were a real shock for me. I realized that I would be discriminated against because I lived …

We are three young people working with the Democratic Movement (MoDem) in the Seine-Saint-Denis neighborhood. We are writing to share our experiences 10 years after the riots rocked all of France, not just our neighborhood. Our goal is to assess the changes that have unfolded over the past 10 years, and, above all, reflect on what remains to be done in areas that have been referred to as “priority neighborhoods.”

I was 12 years-old when the riots broke out in 2005. They were a real shock for me. I realized that I would be discriminated against because I lived in a neighborhood that was considered “difficult,” because my parents belonged to the working-class, and because I was of foreign origin, even though I was born in France. I became aware of my reality, which featured poverty, discrimination and exclusion. It was the end of my childhood innocence.

Ten years have passed since then, filled with promises and investments, but in the end, today’s reality is not that different from that of 10 years ago. Over the past decade, I saw the urban structure of my neighborhood and my city change, and the same is now taking place in other areas. Thanks to different plans put in place by successive administrations and local governments, the housing projects are gradually being taken down. In my neighborhood of Londeau in the suburb Noisy-le-Sec, there are many ongoing projects to modernize the buildings, as well as to purchase properties that were previously used as housing projects. This is a positive move that has helped to increase social diversity in my neighborhood. And generally, it’s the only positive measure taken over the past 10 years.

“Unemployment has not decreased, and poverty still exists with neither improvement nor end in sight.”

But if the urban fabric of the city is changing, the root of the problem is not. The state has failed at the economic level: in my city, young people seem disenchanted, and there’s a real gap between young people who drop out of school and those who go on to pursue higher education. Unemployment has not decreased, and poverty still exists with neither improvement nor end in sight. Nicolas Sarkozy and François Hollande have both failed in that regard: the establishment of tax-free zones and the arrival of big organizations to the Seine-Saint-Denis neighborhood has not improved the employment situation for the youth there. They still feel abandoned, especially after the false promises François Hollande has made during his term. Not to mention discrimination in the workplace. Last August, 122,340 people in Seine-Saint-Denis were still unemployed; in priority neighborhoods, these figures are two to three times higher than the national average.

There are exceptions, and these offer glimmers of hope for an entire generation. One example is a childhood friend of mine, who attended a Priority Education Zone (ZEP) school with me, and then made it to a prestigious preparatory school, and eventually, a prominent business school. Thanks to these ordinary heroes, we can still dare to dream.

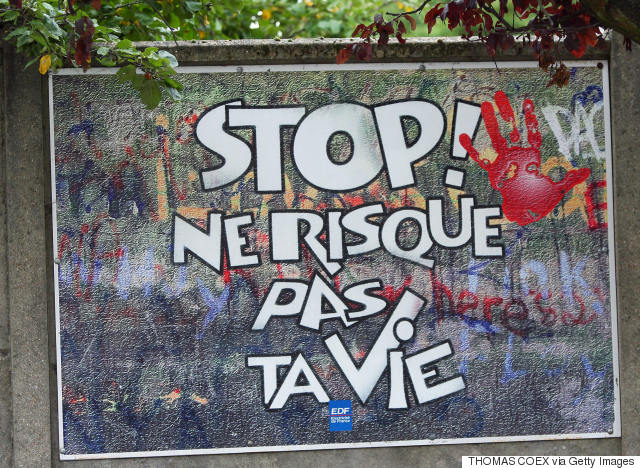

Graffiti near the entrance of a power plant in the northern Paris suburb of Clichy-sous-Bois a billboard reading: ‘Stop ! Don’t Risk Your Life’ at the site where riots erupted on October 27, 2005. Two boys died by electrocution inside a power plant, after being allegedly chased by police.

Graffiti near the entrance of a power plant in the northern Paris suburb of Clichy-sous-Bois a billboard reading: ‘Stop ! Don’t Risk Your Life’ at the site where riots erupted on October 27, 2005. Two boys died by electrocution inside a power plant, after being allegedly chased by police.

I watched the riots of 2005 from my home in the Pays de la Loire region. Like many others, I was glued to the images I was watching on TV, without feeling personally invested in them.

Today, 10 years later, I teach at a school in the Saint-Denis neighborhood that belongs to a ZEP school. In other words, it’s an underprivileged city school. One of the reasons I chose to teach here was to understand the “problem of the suburbs,” as many refer to it. I only recently found out that during the riots, even schools were targeted.

Much has been written on the difficulties of national education in Seine-Saint-Denis. Today, I think that France only needs to understand the background of the people who live in the suburbs.

My school is located in the suburbs, in the ghetto; it is a place where families feel welcome and where they like to meet teachers and take part in their children’s education.

This year, I am teaching a kindergarten class. Every morning before class, I welcome parents who do not speak French; my five year-old students act as my translators. The men and women who I meet are so thrilled to be able to send their kids to school, and through them, overcome the barrier to education. They are proud to vote in the PTA elections, proud to participate in parent meetings, and they become irritated when classes are cancelled.

“Today, I think that France only needs to understand the background of the people who live in the suburbs.”

In many cases, the children are dropped off and picked up by their older siblings. I talk to them as well; I often tell myself that if I have a brief conversation with one of the older siblings, I could dispel, on a small scale, the argument that young people in the suburbs resent France.

Public schools are one of the only places in the suburbs where bonds develop between the people in the suburbs and people in the rest of the country. In school, you are not unemployed, or an immigrant, a delinquent, or an alien. At school, you are the teacher’s main partner in your child’s education.

This is why schools should be appreciated for the role they play in these neighborhoods. They give opportunities to families and their children. They are welcoming homes where teachers and parents work together, in an atmosphere filled with warmth and trust.

Sadly, they are also where there are no substitute teachers, where classrooms are overcrowded, buildings are dilapidated, and equipment is second-hand. The books are always ragged, scribbled over. The boards are just wooden planks painted black.

Two weeks ago, I became very sad when I had to tell the parents that there would be no substitute teacher while I was away for a training course. I hated that I could not give them the real reason: the teacher who was invited to cover for me said they did not want to teach in Saint. Denis. It upset me that the parents were so accustomed to not having substitute teachers. And I was ashamed of my department. Ashamed that it mocked these families by routinely promising them reforms that never happened.

Such is the sad state of the schools of the suburbs. The students and parents protest, but I cannot help but notice that year after year, term after term, their voices are never heard. The national education policy has been somewhat abandoned by the state. There are overwhelming problems: the need to develop new coursework, a shortage of teachers, and the limited budget of the city council.

It’s hard to put on a brave face. But the children’s motivation and the possibility that my determination could help — even slightly — pushes me to teach my class with enthusiasm and perseverance. I don’t do it in the name of my department. I do it to retain my dignity, now that I know that the “problem” of the suburbs is simply that they have been abandoned.

In 2005, I was 13 years old, and living in the center of a city with a population of over 100,000 people. Of the “suburb riots,” I remember the images on TV, and my feelings of incomprehension. I remember the anger, the violence, and the clashes.

The need to understand the social and geographical disparities at the root of these riots eventually led me to Saint-Denis; I now study these issues at University Paris 8. So far, I learned how to get rid of my prejudices, expand my understanding of the world, and in the process, become more tolerant. In my opinion, one of the key functions of college is to liberate people’s minds — intellectually, and socially. But in France today, and particularly in suburbs like Saint-Denis, do colleges have the means to achieve this end?

Schools and higher education universities have an important role to play in integration. Providing schools and universities with sufficient resources, particularly in priority neighborhoods, may encourage the social integration of people who feel ostracized by society, who lose interest in voting, or turn to political parties that claim to be “anti-establishment.”

As a second-year Master’s student at the University Paris 8 in Saint-Denis, I am mentoring undergraduate students this year. Alongside my first year at Saint-Denis, this experience has allowed me to observe firsthand the inequality in French higher education. In France, a preparatory student costs the state four times as much as a university student. Universities lack resources. This is not news, but the fact that “cutting corners” has become the norm is unacceptable. More than 50,000 enrolled students were expected for the 2015 term, and University Paris 8 was not equipped to welcome these new students. In the political science department, the first term had to be postponed due to “a shortage of classrooms.” Many have raised their voices to protest the dire state of colleges, and University Paris 8 in particular. Take for example the Tumblr “Ruines d’Universités” (University Ruins) and the recent report from the Court of Auditors on the financial autonomy of colleges, which revealed that “44 percent of the 15.4 million square-meters of academic institutions property are old or in poor condition.”

“University Paris 8 seems more and more disconnected from its location and the inhabitants of Saint-Denis; the very people it should prioritize.”

President François Hollande’s announcement regarding universities was very disappointing, if not insulting, in light of the current needs. This has reopened the debate on education costs. Besides the cultural importance of having a successfully educated population, sociologists have demonstrated that raising education costs would add an economic barrier that would increase inequality in our education system. While I don’t entirely reject the argument to re-evaluate the costs of education, I think that if they do increase, they should not cripple students from low-income families. And students from the middle class, who are on the border of qualifying for scholarships, should also be taken into account. For this reason, costs should be limited to €500 ($500), in order to avoid aggravating a phenomenon already prevalent in colleges: social selection. I think a review of the scholarship system is equally necessary, so that it may better serve the students who actually need it.

Many of my fellow graduate students also have side-jobs. Working as a mentor, I meet undergraduate students who sometimes work more than 20 hours a week in addition to their coursework. The increase of student employees, which is particularly noticeable at the University of Saint-Denis, is one of the reasons that I am pushing for a more vigilant approach to the college acceptance process. The practice of having an acceptance process between the first and second years of the Master’s program has become widespread. I have seen this firsthand: one of my fellow students, who comes from Seine-Saint-Denis and has completed the first year of the Master’s program and the relevant coursework with honors, was denied entry for the second year of the program. This practice is considered illegal according to recent legislation. She was a victim, however, to the current policy of Paris 8, which is to increase the acceptance rate, notably by accepting a large number of “outside” students, particularly from the Sorbonne. Students who studied at Paris 8 are sidelined. I therefore call for a debate which would involve the students and their representatives, and result in more transparency and honesty with regards to the acceptance process, instead of the opacity that currently shrouds it.

University Paris 8 seems more and more disconnected from its location and the inhabitants of Saint-Denis; the very people it should prioritize. The majority of students who “drop out” are in their first years of their undergraduate programs; which could be limited if the state gave colleges, particularly institutions located within the city’s designated priority neighborhoods, the resources to support students facing economic, social, cultural and language difficulties and obstacles. My hope is that a greater number of students from Seine-Saint-Denis who grew up in the neighborhoods around this institution will make it to Master’s programs and obtain degrees at institutions that are not considered second-class, but as beacons of excellence and places of economic and social dynamism within the city and the neighborhood of Seine-Saint-Denis.

In memory of Zyed, Jean-Jaques, Salah, Jean-Claude, Bouna and Alain.

This post first appeared on HuffPost France and was translated into English.

— This feed and its contents are the property of The Huffington Post, and use is subject to our terms. It may be used for personal consumption, but may not be distributed on a website.

Jump to original:

Ten Years After The Suburban Riots: Three Young People’s Lives in the Paris Suburbs