Earlier this month, Nigerian military forces rescued hundreds of women and girls from a Boko Haram stronghold in the Sambisa forest of Nigeria. According to the UNFPA, 214 of the 234 women and girls rescued were pregnant. This bittersweet development should help us gain a better understanding about the discourse surrounding critiques of French satirical weekly newsmagazine Charlie Hebdo and its cartoons, particularly the one below: Many consider drawing sex slavery victims as ugly, angry, pregnant “welfare queens” to be racist apathy towards the real destruction Boko Haram causes in Nigeria, and an extension of France’s xenophobia of immigrants and Islamophobia towards Muslims. Others …

Earlier this month, Nigerian military forces rescued hundreds of women and girls from a Boko Haram stronghold in the Sambisa forest of Nigeria. According to the UNFPA, 214 of the 234 women and girls rescued were pregnant.

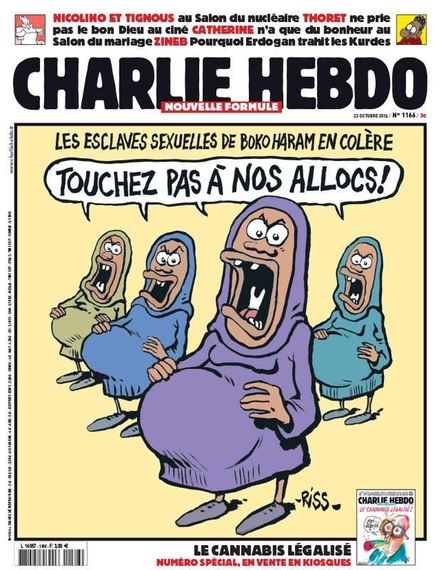

This bittersweet development should help us gain a better understanding about the discourse surrounding critiques of French satirical weekly newsmagazine Charlie Hebdo and its cartoons, particularly the one below:

Many consider drawing sex slavery victims as ugly, angry, pregnant “welfare queens” to be racist apathy towards the real destruction Boko Haram causes in Nigeria, and an extension of France’s xenophobia of immigrants and Islamophobia towards Muslims.

Others see the visceral drawing as a scathing critique of France’s political right. The French right often characterizes immigrants who receive welfare as parasitic to the nation’s economy. Many contend that the cartoon is saying French conservatives are so unreasonable, they would even try to convince French citizenry that Nigerians who escaped sexual slavery are there to steal welfare.

Regardless of the meanings or our reactions to any of Charlie Hebdo’s cartoons, it is difficult to imagine any art so deplorable that it warrants terroristic violence. The attack on the magazine’s office resulted in twelve tragic deaths, leaving the international community shocked, mournful, outraged, and united under “Je Suis Charlie.”

But in the wake of the attack, many have equated criticism of Charlie Hebdo’s cartoons as censoring free speech, disrespecting the victims of the attack, or sympathizing with terrorists. All of these assertions are mostly reactionary and ultimately fallacious. In regards to the above drawing, the criticism is merely a call for empathy towards hundreds of women forced into sexual slavery, made pregnant from mass rape. For many, arguments about who or what is sacred or not is a red herring that privileges certain people’s lives over others.

The wider criticism of stereotypical depictions of Arabs, Muslims, and the prophet Muhammad stems from sensitivity to the dilemma of Muslims around the globe when terrible acts of religious extremism occur. The peaceful vast majority of Muslims have to verbally and physically denounce terrorists (who in their eyes are not truly observing Islam, but subverting it for political gain) while others construe their efforts to debunk global Islamophobia as being “sympathetic” to terrorists.

Though the slain dozen have since been martyrized, Charlie Hebdo was pushed back into the news when a group of authors boycotted PEN America for giving its annual “Freedom of Expression Courage Award” to Charlie Hebdo.

One of those authors, Teju Cole, condemned the terrorist attack, but was concerned that the magazine has gone “specifically for racist and Islamophobic provocations.”

It should be noted that there is much lost in translation for both the non-French critics or supporters of Charlie Hebdo who aren’t privy to French history, culture, and politics. America doesn’t quite have an adequate analogy for France’s long history of political satirization.

Many see the magazine as a free speech champion, rejecting all forms of censorship by challenging taboos and promoting France’s secularist tradition of separating church and state. In regards to its satirization of the prophet Muhammad, Charlie Hebdo essayist Jean-Baptiste Thoret says the magazine is trying to forcefully reject “the efforts of a small minority of radical extremists to place broad categories of speech off limits.”

While Thoret’s words are fair in light of the tragedy, we are snowballing down a slippery slope by conflating negative reactions to Charlie Hebdo’s cartoons as tacit approval of hateful violence. Decrying terrorism and taking issue with racist or xenophobic cartoons aren’t mutually exclusive actions.

As writer Arthur Chu said in his piece for The Daily Beast:

“The public discourse isn’t between people who think they ‘asked for it’ and people who don’t–it’s entirely among people who agree that the violence was unacceptable, but some of whom feel that this obligates them to elevate Charlie Hebdo to heroes and to hold up “Je Suis Charlie” signs, and others who don’t.”

It also raised questions about double standards in free speech. Charlie Hebdo and its supporters often buttress the “equal opportunist” ideology behind satirical cartoons that utilize stereotypical depictions. But in 2009, cartoonist Maurice Sinet was fired from Charlie Hebdo and put on trial for an anti-Semitism.

What has often gone missing from recent mainstream discourse about free speech is that satire can question power, but it can also preserve it. In the NYT, author Saladin Ahmed critiqued the widely accepted “no one is off limits” premise of satire for its tendency to privilege those in power over marginalized groups.

“The belief that satire is a courageous art beholden to no one is intoxicating,” Ahmed said. “But satire might be better served by an honest reckoning of whose voices we hear and don’t hear, of who we mock and who we don’t, and why.”

Counterintuitively, the rebuttals of many Charlie Hebdo supporters to criticism raise deeper questions about the provocateur role if the satire is not truly aimed in all directions.

If satire is meant to shame society into bettering itself, can satire be shamed by society into bettering itself? What is it to be gained by making depictions of rape victims fair game? Would the above cartoon exist if Boko Haram had kidnapped white Parisian Catholic school girls and made them pregnant from sex slavery? If so, would the depiction or the point be different? Would the public be more critical or would it be sentinels of free speech?

Regardless of anyone’s opinion of the publication, no one should be killed because of a political cartoon. Anyone praising the loss of life over an artistic and political issue is an opponent to much more than free speech. But critics of the above cartoon were simply upset with those who think it is fair to use the rape of hundreds of African women and girls to make an ironic point.

The cultural war behind free speech has created victims and martyrs on all sides. So even if we disagree about ideas around free speech, the role of the provocateur, or the criticism of Charlie Hebdo cartoons, at least we can now more fully understand pain and anger from those witnessing nightmares come to life. Arguing to preserve the dignity of raped women and mourning the lives lost at Charlie Hebdo isn’t an either or thing.

To quote Cole, “Moments of grief neither rob us of our complexity nor absolve us of the responsibility of making distinctions.”

— This feed and its contents are the property of The Huffington Post, and use is subject to our terms. It may be used for personal consumption, but may not be distributed on a website.

Excerpt from:

Rescued Nigerian Girls Should Help Us Understand Criticism of ‘Charlie Hebdo’ Cartoons