MALINDI, Kenya — Heroin addicts in the Kenyan coastal town of Malindi used to call Mohamed Said Mapera “The Doctor.” He was one of the first people in the area to inject heroin in the late 1980s, and taught new addicts how to shoot up, in exchange for a cut of their drugs. These days, ‘The Doctor’ is 46 years old, clean, and a trained paramedic. He works for The Omari Project, a pioneering community-based organization in the struggling tourist town of Malindi, providing treatment and support to heroin addicts in this forgotten hotspot of the international drugs trade. Around half of its staff are themselves recovering addicts. &ldquo…

MALINDI, Kenya — Heroin addicts in the Kenyan coastal town of Malindi used to call Mohamed Said Mapera “The Doctor.” He was one of the first people in the area to inject heroin in the late 1980s, and taught new addicts how to shoot up, in exchange for a cut of their drugs.

These days, ‘The Doctor’ is 46 years old, clean, and a trained paramedic. He works for The Omari Project, a pioneering community-based organization in the struggling tourist town of Malindi, providing treatment and support to heroin addicts in this forgotten hotspot of the international drugs trade. Around half of its staff are themselves recovering addicts.

“He’s the one who used to inject us,” Ummi Khalid, a 39-year-old outreach worker at the Omari Project who has been clean for ten years, told The WorldPost. “But now we work together as colleagues,” she said. Mapera feels sick about those earlier days, when he sat at the center of Malindi’s heroin epidemic. “I didn’t know myself,” he said.

Mapera hasn’t used heroin since 2007, after spending a year at The Omari Project’s rehabilitation center. “Most of the people in Malindi didn’t believe that I could quit this stuff,” he told The WorldPost. He had been into the drug for so long that he was reduced to injecting heroin into his penis. Now, addicts and their families look to him as a role model. He is living proof that people can recover.

The Omari Project was founded in 1995, named after the first injection drug user in Malindi who died after using a contaminated needle. Since then, heroin addiction has been on the rise in Kenya, as the eastern African route for the heroin trade has exploded.

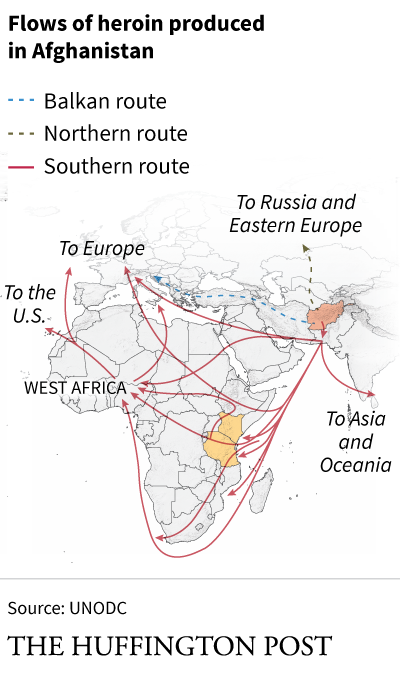

Most of the world’s heroin is produced in Afghanistan, and reaches markets in Europe and North America via Central Asia and the Balkans. Yet the amount of heroin seized off the coast of Kenya and neighboring Tanzania has increased exponentially in the last six years, leading United Nations’ experts to surmise that the “southern route,” also known as the smack track, is growing in importance to drug cartels.

Last year, for example, a 30-nation maritime force meant to protect ships from pirates seized more heroin in the Indian Ocean than the previous three years combined, the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime said. The shift, UNODC officials say, is likely due to a crackdown on drug trafficking in central Europe and the war in Syria, pushing cartels to experiment with new routes.

As more heroin floods into East Africa, more and more Kenyans are getting hooked on the drug. While data on heroin users in Kenya is limited, the UNODC has warned that heroin addiction appears to be on the rise in the country, particularly along the coast, including the city of Mombasa, home to East Africa’s largest port, and the town of Malindi, 70 miles north of the city. The United Nations estimates that around 18,000 people inject drugs in Kenya, with 10,000 of them living on the coast. “It’s clear that the coast is an entry point, and wherever there’s a path, there are some crumbs left behind,” Sylvie Bertrand, regional adviser for HIV/AIDS at UNODC’s Eastern Africa office, told The WorldPost.

Heroin first became readily available in Malindi during the 1980s tourism boom. In the 1990s, the most commonly available form of heroin switched from “brown sugar,” which is often inhaled, to “white crest,” which can be smoked or injected. Injection drug use slowly took off.

At the time, British social anthropologist Susan Beckerleg, who died in 2012, began investigating Kenya’s burgeoning heroin epidemic, and along with colleagues at the Bristol Drugs Project, helped the community establish The Omari Project. The project has been working to tackle Malindi’s heroin problem for two decades.

Today, The Omari Project has a 24-bed rehabilitation center, (which originally was free, but now has to charge patients around $150 per month because of a lack of donor funds), a free outreach program, a drop-in center and offers counseling, medical treatment and other forms of support to drug users.

The Kenyan government has vowed to crack down on the drugs trade, but few high-level arrests have been made. Many Kenyans say authorities either have been in denial, turned a blind eye, or took bribes from the cartels over the years as the heroin epidemic spiraled.

Though Kenya has made little progress combatting the trade, the country is gradually moving forward with a groundbreaking shift in responding to addiction. Historically, law enforcement and some drug treatment programs in Kenya, as in many other countries, have focused on eliminating drug use, but now the country is embracing a move towards treating drug addiction as a public health, rather than solely a criminal justice, issue. This includes Kenya’s recent adoption of “harm reduction” strategies, which seek to reduce the health risks and other harms caused by drug use. The concept of harm reduction is new and very limited in Africa — out of 42 countries in mainland sub-Saharan Africa, only five, including Kenya, have some form of harm reduction strategies, according to Harm Reduction International.

Harm reduction strategies, such as needle and syringe exchanges, or methadone treatment, are politically controversial in many parts of the world, including in the U.S. Critics argue for example that providing clean needles encourages drug use, or that methadone programs, which alleviate heroin’s grueling withdrawal symptoms, just replace one addiction with another. The World Health Organization, however, says that such measures do not cause an increase in drug use and are the most effective way of reducing HIV prevalence among drug users.

Combatting the transmission of HIV is a major challenge for Kenya — the country has one of the world’s largest AIDS epidemics. Injection drug users are among those most at risk of being infected by HIV. Some 20 percent of Kenyan injection drug users already live with HIV, compared with around 6 percent of the total population.

Organizations like The Omari Project have been at the forefront of Kenya’s shift towards harm reduction strategies. The project introduced one of Kenya’s first needle and syringe exchange programs in 2012, despite initial resistance from both the community and local police.

Legal confusion has added to the difficulties surrounding the exchange program. While the program is part of a government-backed initiative, it remains illegal in Kenya to possess injecting paraphernalia.

“There is a contradiction between the right to health, which is enshrined in law, and the criminal laws,” Omari Project program coordinator Showsee Mohamed, 51, told The WorldPost in an interview last month. “But we said we’re going to do it, and we’ll see who will take us to jail. Drug use is an offense, but HIV prevention while using drugs shouldn’t be offense.”

Mohamed says the police visited him in response to community complaints several months after the program launched. However, he managed to convince them that the program had the support of government health authorities. The police in Malindi no longer interfere with the needle and syringe program, even though pockets of the community remain uncomfortable with it, according to Mohamed.

The program has also faced funding problems. The largest donor to HIV prevention in the country, the U.S. government, bans federal funding for needle and syringe exchange programs. President Barack Obama tried to end the ban in 2009 but was overruled by Congress two years later. “That is a big problem as the U.S. is by far the largest donor to HIV prevention in Kenya and Tanzania,” Ancella Voets, the training and resource centre coordinator for Kenya and Tanzania for French humanitarian organization Médecins du Monde, told The WorldPost.

Across the globe, the United States made up more than half of all foreign government spending on HIV response last year. “In the long term, it’s really worrying … For those who are not ready to quit, needle and syringe programs are literally their lifesaver,” Voets said. “If you don’t provide clean syringes you can tell people what you want, but they’re going to use syringes, and get HIV, and die, in the end.”

It was difficult for The Omari Project to find non-U.S. funds for its needle exchange program, Mohamed said, but they eventually found other donors — the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, and the Netherlands-based Mainline Foundation.

The organization’s outreach workers patrol the back alleys of Malindi, providing education, medical care and clean needles to hundreds of addicts.

After years of advocacy from international organizations and local groups like The Omari Project, Kenya began its first methadone program this summer in partnership with the UNODC and the University of Maryland, and with funding from the U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Over 700 people have already been enrolled in methadone treatment in three locations — in Malindi and Mombasa on the coast, and in the capital city of Nairobi. The Omari Project has enrolled 145 people in the national methadone program since it was launched in Malindi in February.

Omari Project staff screen participants, provide counseling and support, and accompany them to a clinic in a nearby government hospital where the methadone is administered.

Kenya is slowly following in the pioneering footsteps of neighboring Tanzania, which introduced the first methadone program in East Africa in 2011, and has since enrolled over 1,000 people in the program in the capital city of Dar es Salaam.

Methadone was the “missing link to protect people who inject drugs” in Kenya, the UNODC’s Bertrand said. “Kenya is a powerhouse for the region, so the influence and importance of this project is trailblazing,” she said. “For the first time there is a comprehensive response, where the needs of people who inject drugs are met, and they have a say in the delivery of their services.”

On a late October afternoon, a group of men who are taking part in the methadone program at The Omari Project drop-in center showed off their biceps and full figures proudly — they did not look so healthy just a few months ago, they said.

“They put on weight, they reconnect with their families, they reconnect with their faith … there are so many changes that happen in the lives of a person that embarks on this program,” Bertrand said, describing the impact of the methadone program along the Kenyan coast.

The Omari Project says it has helped around 80 percent of the people in the methadone program to get back to work, including 49-year-old Mwikali William, who had been using heroin for 21 years before she became the third person to sign up to The Omari Project’s methadone program in February. Now she has a roadside stall where she cooks chapati, french fries and beans to sell to minibus drivers.

“Methadone has been really helpful as I don’t need to worry about drugs or where I’m going to get my next dose,” William told The WorldPost. “I’ve not been home to see my children in eastern Kenya for 10 years and now I’m looking for money to get home.”

Getting former addicts back into work is crucial, Mohamed explained, because heroin users who are not able to hold down a job may resort to crime, and in economically-depressed Malindi, thieves are treated harshly. “If you touch somebody’s property, you’ll be beaten to death,” Showsee said. “So many people have died through mob justice here.” The Kenyan coast is suffering from the economic fallout of attacks by Somali militant group al-Shabab, which has damaged the area’s tourism-driven economy.

Heroin users are still frequently arrested by police — there were mass arrests in nearby Mombasa recently — but The Omari Project has an agreement with the probation office to offer treatment as an alternative to incarceration in certain cases. “I went to jail many times, so I know how prison is, especially for women,” Monica Wanjaa, 32, The Omari Project’s paralegal officer, who has been clean for seven years, said. She now argues in court on behalf of organization’s clients. “When we were addicts we didn’t know our rights. Anything can happen to you and you don’t know where you can go.”

For all the methadone program’s successes, the need is so great that The Omari Project is struggling to keep up. They had to stop enrolling new participants in the methadone program in April, just two months after it had begun.

Heroin users see people on methadone looking clean and healthy, and come begging The Omari Project to open up more spaces on the program, Wanjaa said.

That late October afternoon, one man hurtled into their offices in rage and desperation, demanding to be let into the methadone preparation meeting underway in the conference room. “Give me methadone, give me heroin, or let me die!” he bellowed. But, he is already on a waiting list for when a new space opens up, and the staff gently turned him away, his yells echoing down the orange, dusty road.

The partnership between government health authorities and civil society has not been always been easy. Mohamed said some of the government health workers in the methadone clinics do not have experience working with drug users and still carry prejudices and misunderstandings.

Yet, Bertrand insists this partnership will be critical to the success of the program, and could be a good example to other African countries with heroin epidemics. Community organizations “were there well before other service providers, so they have the advantage of knowing the epidemic and knowing the clients,” Bertrand said.

“Making history is not always easy, of course,” she said.

And many of The Omari Project’s staff have an intimate knowledge of the epidemic — because they were once a part of it.

“I do this job because I was there” said 39-year-old outreach worker Bakari Hatib, trailing off in a long sigh as tears swum in his eyes. Hatib started using heroin when he was 18 years old, and has been clean for seven years. “Now when I am in a support meeting, I see the faces of the clients and I think ‘Wow, I’m not alone anymore.’”

“I can go anywhere, and talk to anyone, without being shy,” Wanjaa said about her outreach work with heroin users in Malindi. “They all know me from a long time ago. We ate from the dustbin together once upon a time.”

Even staff who have never used heroin are painfully acquainted with its effects. Mohamed started working at The Omari Project in 2000 because one of his closest friends was addicted to heroin and he had no idea what to do about it. He got his friend into the rehabilitation center, but he relapsed after one month and died three months later from liver complications. His friend’s brother died two months later after an overdose. His friend’s sister is alive, but still addicted to heroin. Her two children also got hooked, but they are now in the methadone program.

Mohamed says breaking the widespread stigma around addiction is critical to the project’s success. His friends often wonder at the respect he gets from heroin users when they walk together around town. “I tell people: ‘The difference between us is that you treat them as junkies and criminals, and we treat them as humans,’” he said. “It’s nothing new I’m doing here. This world is a mirror. If you smile it smiles back. If you frown it frowns back at you.”

Also on HuffPost:

— This feed and its contents are the property of The Huffington Post, and use is subject to our terms. It may be used for personal consumption, but may not be distributed on a website.

Originally posted here: