The scar over my grandfather’s left eye tells a story, and it is this: In 1930, my maternal grandparents Prisciliano and Francisca Sánchez were married in Indiana Harbor, Indiana (pictured above). Though technically across the state line, Indiana Harbor is part of Chicago’s sprawling metropolitan empire, not too far from downtown’s picture postcard shoreline. My grandparents lived in a neighborhood that was predominantly Mexican: They rented a small apartment and began buying pieces of furniture to outfit their new life. They had their wedding photo framed. A year later, Francisca gave birth to their first child, a girl they named María de la Luz. (Mary of the Light, if English leant itself to such lyrically faith-filled names….

The scar over my grandfather’s left eye tells a story, and it is this: In 1930, my maternal grandparents Prisciliano and Francisca Sánchez were married in Indiana Harbor, Indiana (pictured above). Though technically across the state line, Indiana Harbor is part of Chicago’s sprawling metropolitan empire, not too far from downtown’s picture postcard shoreline.

My grandparents lived in a neighborhood that was predominantly Mexican: They rented a small apartment and began buying pieces of furniture to outfit their new life. They had their wedding photo framed. A year later, Francisca gave birth to their first child, a girl they named María de la Luz. (Mary of the Light, if English leant itself to such lyrically faith-filled names.)

In 1932, Francisca became pregnant with their second child, who would be a son. Also in 1932, white cops stopped Prisciliano and almost beat him to death: Another punch, maybe another kick or two, and my grandmother would have been a widow on the eve of her thirtieth birthday.

This is the story that Prisciliano’s friends, who carried him home to the little apartment, told Francisca, and which she in turn told her children: The cops often harassed Mexican men, less-than-welcoming to the new immigrants on the block. Many of the police were also Catholic, according to Francisca, but in 1930s Chicago, that meant nothing. The old fairy tales of Irish American soldiers deserting U.S. forces during the 1846-48 War, and joining their fellow Catholics on the Mexican side, were just that – fables of a very distant past.

The police were white, American white, at least in their own minds. My grandparents, on the other hand, possessed only the most fragile, tenuous claims to any Europeanness. Between them, three of their four parents were, in old terms, criollos: Mexicans of Spanish ancestry. In the United States, though, that term was meaningless, as weightless as old alliances recorded in history books; even my grandparents themselves never would have used the word.

Prisciliano and Francisca were not white in this country, and that was that. Thus the cops would stop Mexican men like my grandfather, mocking their accents, belittling their darker skins, and they would ask the men for their names. In an effort to defuse the situation, many Mexicanos would adopt Irish surnames right on the spot. “My name is Juan O’Reilly.” “Manuel O’Brien.” “My name, it’s Felipe O’Malley, señor.” O’Reilly, O’Malley, O’Something — whatever names they had heard and knew.

No one believed any of this, according to my grandfather’s friends. It was a charade for the moment, an imposed deference to the greater power of the men with badges — an obeisance to the greater social legitimacy of the police and the institution that paid them. Everyone knew it was a farce, and everyone joined in. They were supposed to, at least.

Prisciliano, however, wore his national pride with the same swagger with which he dressed himself in tailored suits and carefully chosen fedoras. He’d come to the United States, to Chicago, almost ten years earlier during Mexico’s endlessly brutal revolution. In his retelling, the flight from his homeland was imagined and then acted upon in less than a day. In the middle of the war — when it seemed to have gone on so long already, and yet still had so long to go — federal forces came to my grandfather’s home town, and shot two of his brothers dead. The boys “failed to volunteer” to join the federalistas, and thus they died.

Later that night, before his siblings were even buried, my grandfather kissed his mother goodbye, and began the two thousand mile journey from Encarnación de Díaz, in the southern state of Jalisco, to Chicago. Leave quickly, and live another day. Two thousand miles: Through war zones, and then through a strange country with a language he didn’t then know. And yet he made it. If he could survive that, he could survive anything, right? So when the cops stopped my grandfather and his friends that night in 1932, my grandfather did not join in the charade. He spoke his name clearly and slowly: Prisciliano Sánchez Olmedo. He held his head high. And then the first cop hit him.

Francisca said that she thought my grandfather would die that night. The blood obscured the features of the man she loved, and the blood was surrounded by noise — his moans, his friends’ frantic debate over what to do first, her toddler daughter beginning to cry. Someone went for a doctor, and someone else went for Francisca’s sister and brother-in-law who lived nearby. A neighbor came and picked up baby Luz, trying to rock her and comfort her. Another made my grandmother tea; when my great-aunt arrived, she hovered over her younger, pregnant, and terrified sister. My great-aunt was scared too; everyone was.

Fear was the strongest thing in the room, pulling at and controlling everything and everyone. The doctor came. My grandfather was in bed for days, not working. Friends came, brought food, watched the baby; my great-aunt never left her sister’s side. Eventually my grandfather got better. Even with healing injuries, he was still young and strong, and of course, he was cheap immigrant labor, so he got another job quickly. The Great Depression, though, was settling in for a long stay, and the fear that had entered the apartment with my grandfather’s limp body never left, not for Francisca. Times were hard, and people became hard with them. My grandparents’ second baby had come, and Francisca worried about her husband constantly. What if it happened again? What if they were not “lucky” this time?

My grandparents gave their notice, packed the furniture and the wedding photo, and bought train tickets. They did not go to Jalisco, but to Coahuila, Francisca’s home state in the north of the country. There they found a small house near that of her parents, on a street where everyone — Riveras, Adáns, Martinezes, Gómezes – was related in some way.

When they were older — María de la Luz, José, and then later, Antonieta and Conchita — Francisca told her children about how the racist police had nearly killed their father. How they had ruined our life in Chicago. How they threatened other men, and thus other women and other children, every single day. In Coahuila, though, everyone liked her husband, and her, and her children. No one made fun of their accents, their skin, their food, their Virgin Mary, their anything. Aunts and uncles, cousins, in-laws, and the large soft web of familia were everywhere. No threats, and no fear.

This is the story that Francisca told her children, and that they told me. Prisciliano did not tell the story of his beating at the hands of white cops. The stories that he did tell — to me, his only granddaughter — were actually stories of love. Chicago was the place where his escape led him: A huge expanse of lights and life, of refuge from war. In Chicago he got good jobs, and could buy the nice clothes he took so much pleasure in wearing. Chicago was where he met the most beautiful woman in the world, the norteña with reddish-brown hair whose picture he kept tucked into his Bible. We found it there when he died, protected in a small plastic sleeve amongst the pages of the Psalms. (“Surely goodness and mercy shall follow me all the days of my life, and I shall dwell in the house of the Lord forever.”)

My grandfather only told me how much he loved Chicago — and Jalisco, and mariachi, and baseball, and a shot of tequila in his morning coffee “to start up my heart.” He loved growing tomatoes and peppers in the backyard; he loved the pale sunsets of the Midwest in winter. He loved his wife, and his children, and me. And I, in turn, adored him — adore him still, in his grave.

There was one part of the story, though, that told itself despite him: The scar above his left eye. A small rift of skin, joined eventually by wrinkles and yet, not quite of them. I knew that scar. And so his reticence was of no matter: When my mother, and my aunts, and my uncle, told me the story of his beating, I recognized it. I knew it as well as I knew his kind and loving face.

***

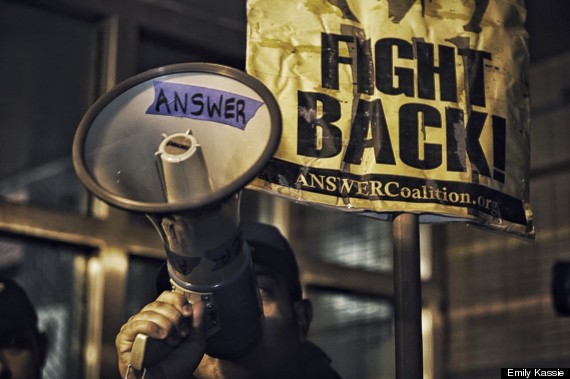

I have been thinking of these stories, the one uttered and the one worn in my grandfather’s skin, ever since Michael Brown’s death in Ferguson, Missouri on August 9th.

I actually think of these stories frequently: I think of them every time I hear of a black man or a Latino man being killed by police. I think of related stories over the years from friends, colleagues, and students I have taught: men being stopped, questioned, followed, treated with disdain and disrespect, suspicion, and always, with violence looming, instantly there, filling up a car, a street, a campus, materialized as if plucked from the air. Mostly men, though not always.

And I think, well, it happened to my grandfather. It happened to Sara’s brother, and my student Jaime, and my mom’s friend Rudy, and on and on and on. I mean, we’re fucking Latino in the United States — what are the chances I wouldn’t know stories of our men, and of our black neighbors, friends, lovers, coworkers, fellow citizens, being harassed by police? Do I really have to say that is almost always white police? (I am trying to think, as I write this, if any of the stories I know are not about white police, and I am coming up empty.)

The point of this is not to provide hard data — the numbers and facts that are volleyed back and forth, like so much ammunition, in every form of media we have. The data are meaningless, and they do not move us; activists and politicians, lobbyists and prosecutors, friends about to unfriend each other and family about to sit down to very uncomfortable dinners, scream numbers at each other every day, and nothing changes.

What I care about most is story: It is stories that crawl inside our hearts, lodge themselves in our consciences, make themselves comfortable and at home in our memories. How could I ever forget that scar on my grandfather’s face? Can I forget how it felt to be held with such love, to be smiled at as if I were, in fact, “una princesa” just like he said? The moment when I learned why that scar was there is just as permanently settled in my mind as my grandfather’s love is settled in my heart.

Stories like these cannot be untold and they cannot be undone. More constant than law, than nation, than theories such as “we hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal,” stories put down roots, they live and persevere. They survive.

Thus, when I hear of black and Latino men being stopped, being searched, being harassed, being beaten, being shot, being killed, I never think, well, this has nothing to do with race. Laughable; contemptuously laughable. The very idea that somehow, of all areas of life, this is the one where race does not enter, makes me shake with anger.

It’s always about race. Every dawn I have lived and every story that has come with that dawn has taught me this. But I do not expect to convince anyone with this telling of my own. I write it down, in part, because I am thinking of the stories that Michael Brown’s family will now tell. I have seen the pain etched into his mother’s face, and I recognize it. I’ve heard the anger in his father’s voice, and that, too, is as familiar as my own mother’s tones. I believe them, I believe their son was murdered, and I believe our “justice system” failed them. I believe it as instinctively as I believe that right now, I am typing, reading, correcting, breathing, telling. So many stories: Mike Brown’s, and Eric Garner’s, and Tamir Rice’s, Oscar Grant’s, John Crawford’s… but none of them as “lucky” as my family. All of their stories take the place of their lives.

Both Prisciliano and Francisca are dead. So are two of their children. But I have inherited their stories, the ones they told, and the ones they wore written on their faces. So now these are my stories, and I pass them on. Right now, I tell them to you. Make of them what you will — I tell them nonetheless.

Originally from:

The American Stories That Cannot Be Untold