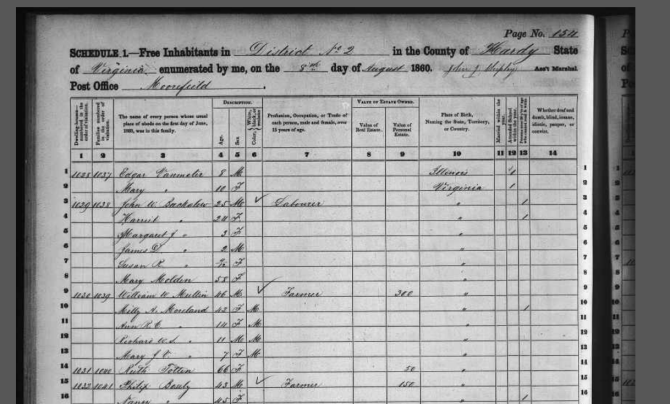

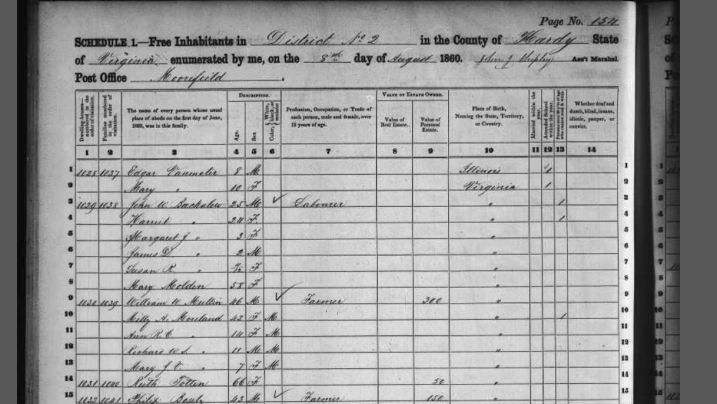

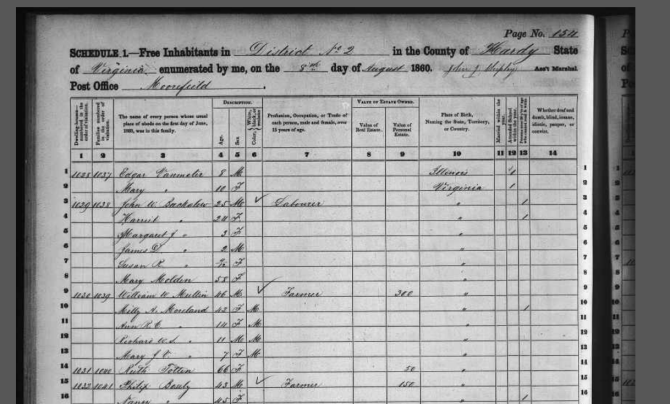

1860 U.S. census for Hardy County, Va.

U.S. census

I recently discovered that I have an ancestor listed as “mulatto” on the 1850 and 1860 census records. Her name is Amelia “Millie/Milly” A. Moreland, born in 1818 in Virginia. She is listed as living with William White Mullin and three children, Richard Winfield Scott Moreland, Anna R.C. Moreland and Mary J.V. Moreland—all children also listed as “mulatto.” By the 1900 census, son Richard changed his surname to Mullin (he was still listed as Moreland/Mooreland on the 1880 census) and was listed as “white.” He is my fourth-great-grandfather. They were located in Hardy County, Va. (now in West Virginia).

These census records are all I can find. I can’t find anything on Milly except her birth year and place, and I’m not sure if she was free or a slave. Can you help me find out more about her, please? —Amber Simmons

It just so happens that three sets of Professor Gates’ fourth-great-grandparents (all free Negroes) lived in Hardy County, Va. (now West Virginia), in the 18th and 19th centuries. In fact, many of their descendants continued to live there; in fact, Professor Gates was born in Keyser, W.Va., which is 36 miles from Moorefield, Hardy County’s county seat! So he knows this area very, very well, and finds your question especially intriguing because of this personal connection.

What does a “mulatto” designation mean in the census?

Let’s start with a surprising fact about racial designations and census takers: The status of a person listed in the federal census (black, white or mulatto) was ultimately the personal interpretation of the census taker, based on assumptions made regarding skin color and other aspects of an individual’s appearance, regardless of what the occupant of the home told her or him. Therefore, one can’t necessarily infer parentage, complexion, or much else based on that designation in a census record. However, in this case, it’s an indication that a local person was making a declaration of mixed-race ancestry (either recent or older) in your relative’s family tree.

In fact, when we consulted professional researcher Jane Ailes, who worked on Professor Gates’ own family history for the PBS series African American Lives, she pointed out to us in an email that the census taker for Hardy County in 1850 was John C.B. Mullin, brother of William White Mullin, the white man identified in the 1860 census as the head of the household in which Amelia “Millie/Milly” A. Moreland lived. (John C.B. Mullin also ran the Mullin Hotel in Moorefield.) As you noted, Amelia “Millie/Milly” A. Moreland was listed as “mulatto” in the 1850 census. No doubt, the census taker knew her heritage.

Young Richard Winfield Scott Moreland’s adoption of William’s surname Mullin in later records, and the change in his identity from “mulatto” to “white” are certainly worth noting in this context. Information revealed further on in this column underscores the significance of that action; but clearly, Richard was light-skinned enough to be identified as white in later periods. Whether he deliberately decided to “pass” as white cannot be deduced from the census record, although it is possible. Ailes suggests another possible scenario: that he was designated as white in the census as a “recognition of status” relating to his affiliation with the Mullin family.

Was Milly Moreland enslaved or free?

A significant aspect of the history of Milly Moreland can be ascertained simply by paying attention to the years in which she appears in the U.S. census. We know that she was free at least as early as 1850, since most persons who were enslaved do not appear in the census records until 1870.

What is more difficult to determine is whether Milly started her life as free or was formerly enslaved and freed upon the death of a former owner prior to 1850. Most formerly enslaved people, of course, had received their freedom from white slaveholders. And some slaveholders did, in fact, free their mixed-race children, but not all did. Sometimes, though much more rarely, a mixed-raced person could trace her or his freedom back to a white mother. FamilySearch notes on its “Virginia African Americans” page, “many free people of color descended from black slave men who had children by white indentured servant women.” However, that lineage is relatively rare, compared to the scenario of white man fathering a mixed-race child with an enslaved black woman.

We asked Ailes to provide further insight on how to investigate Milly’s status. She told us in an email, “[In Virginia] during Milly’s lifetime, a child followed the status of the mother, never the father, so her mother may have been a free woman of color, or a white woman who had a child with a man of color who was either free or a slave.” (Rules for determining the status of mixed-race children changed over time and varied by state; in neighboring Maryland, the child’s condition followed the father’s between 1664 and 1681.)

Ailes suggests going through Hardy County court records, beginning with a few years before Millie’s assumed birth in 1818 (just in case the source of that birth date is inaccurate). “If her mother was white, it’s likely that she was taken into court to require the father to provide financial support, or accuse him of rape, or both,” explained Ailes. “After the child is born, the child is sometimes named in the court record. Of course, there were also the times when the family kept it out of court, so there would be no record.”

It’s also possible that either Milly or her mother was freed by deed or will, Ailes offered. You could look for Milly in the free Negro registration records for Hardy County and neighboring counties. The original registration book itself for Hardy County isn’t extant, “but each time someone came in to register, it was approved in court, so there are a few lines in the County Court Books for each registration.” You’d have to search page by page through the court books.

To search for more clues to the Moreland lineage, you would want to begin by identifying all other households with the surname Moreland/Mooreland in the vicinity of Milly Moreland. It can be tricky to find relevant matches for areas that have changed state lines, like Hardy County, because in popular database search engines, like those available through Ancestry.com, there will not be the option to search for Hardy County, Va. Instead, you should designate your search location as simply “Virginia” and then specify “Hardy” in the keyword bar. Employing this technique for the 1850 U.S. census, we learn that there were a number of white Mooreland families living in Hardy County at the same time as Milly Moreland, all of which you should analyze for anything that might connect them to her.

For example, in the 1850 household of Isaac and Mary Mooreland, there is a girl by the name of Elizabeth J.V. Mooreland, which is somewhat similar to the name of Milly Moreland’s daughter, Mary J.V. Moreland, and might signify a connection between the two families. Keeping with the search for related names, often middle names signify certain family relationships, so you might want to look for other instances of the name “Winfield Scott” in case Richard W.S. Moreland was named after a relative of his mother, although it is worth noting that there was a Gen. Winfield Scott who was active during this time period, and it was not uncommon for people to name their children after well-known political or military figures.

Another factor to look for would be older, widowed women with the Moreland surname. If Milly had been enslaved and then freed after the death of a slaveholding father prior to 1850, identifying households absent an older white male could point you in the direction of her ancestral ties. You will note that there are three older, widowed women in these households: Christina, Hannah and Mary Mooreland. Determining the identity of these women’s husbands will allow you to search for information on when they died and if they left probate records that you can search for mentions of Milly Moreland.

You can also search for Moreland/Mooreland probate records more broadly with Ancestry.com’s newly expanded collection of probate records.

You will want to browse each page of these probate records to search for any mention of Milly/Amelia Moreland. If these do not yield results, you can also order microfilm for Hardy County, W.Va., to be sent to your nearest Family History Center to browse the full collections yourself. FamilySearch has a list of resources for Hardy County, many of which can be ordered via your nearest Family History Center.

You can also search for other records available online through volunteer-maintained sites or other organizations. For example, we discovered through the website West Virginia Culture that an Amelia Mooreland bore a stillborn male child with no designated name on May 7, 1856, in Hardy County. The child was described as “free” and “colored,” and his father is listed as unknown. However, just above Amelia’s name you can see that Rebecca and June Mooreland also had children in Hardy County in 1856. Their husbands were William and Henry, respectively, and the children born to these couples (Hiram L. and Ann V. Mooreland) were described as white. Looking into these individuals might provide you with more information and family links to help learn something of Millie’s history.

Who was the father of her son Richard?

Also through West Virginia Culture, we found records regarding Richard W.S. Moreland, including a marriage record for him and Hannah Catherine Mumbert filed on Sept. 28, 1869. In the record, Richard W.S. Moreland explains that his father was deceased and his mother was named Anna Amelea (sic) Moreland, which provides you with an alternative name for Milly that you might not have come across in other records.

You will also want to view Richard W.S. Moreland/Mullin’s death record from Oct. 27, 1924, in case it contains any additional information about his parents. West Virginia Culture offers this record, which names a W.S. Mullin’s father as W.W. Mullin (perhaps this is William White Mullin?) and for his mother’s maiden name, it appears to state “not Moreland,” though Ailes reviewed it and noted an erasure with the word “not” written over it.

This record, which we assume is for Richard W.S. Moreland/Mullin, is quite curious as it suggests that Milly Moreland may have been previously married and there is the possibility that William White Mullin was not the father of all of her children. However, it is likely that he was the father of Richard W.S. Mullin given that the latter was born so close to 1850 when they were found in the census together and that William (“W.W.”) was listed on Richard’s death certificate. We should note that Ailes did not concur with this scenario, noting that no family relationships were specified in the census record.

What’s next in the search for Milly’s origins?

The best place to turn from here would be to contact or visit local libraries and other organizations that might have other records such as vital records, land records or old newspapers that can shed more light on this family history. It will likely be tricky to determine Milly Moreland’s history prior to 1850, especially if her maiden name was not Moreland, but taking advantage of institutions in and around Hardy County will give you the best chance of finding more information.

Locating a death record for Millie Moreland would be particularly helpful, as it could list her parents or place of birth. Another helpful source would be a marriage record for William and Milly, although there remains the possibility that they were never formally married.

Finally, you will want to research the other two children of Milly Mooreland: Anna R.C. and Mary J.V. Moreland. They seem to disappear from the records we were able to browse after 1860, but finding other records that mention them might be as revealing as those we found for Richard W.S. Moreland, if not more so.

For a list of organizations that you can reach out to, consult West Virginia Culture, which provides both a page dedicated to Hardy County resources and a research request option. The Hardy County, W.Va., GenWeb page offers a list of fellow family historians according to associated surnames. You could contact those individuals connected to the Mooreland surname in the event that they have family records that are useful.

Finally, you might find the Hardy County Public Library and the Hardy County Historical Society to be helpful.

Henry Louis Gates Jr. is the Alphonse Fletcher University Professor and founding director of the Hutchins Center for African and African American Research at Harvard University. He is also chairman of The Root. Follow him on Twitter and Facebook.

Send your questions about tracing your own roots to TracingYourRoots@theroot.com.

This answer was provided in consultation with Anna L. Todd, a researcher from the New England Historic Genealogical Society. Founded in 1845, NEHGS is the country’s leading nonprofit resource for family history research. Its website, AmericanAncestors.org, contains more than 300 million searchable records for research in New England, New York and beyond. With the leading experts in the field, NEHGS staff can provide assistance and guidance for questions in most research areas. They can also be hired to conduct research on your family. Learn more today about researching African-American roots.

Like The Root on Facebook. Follow us on Twitter.