[ad_1]

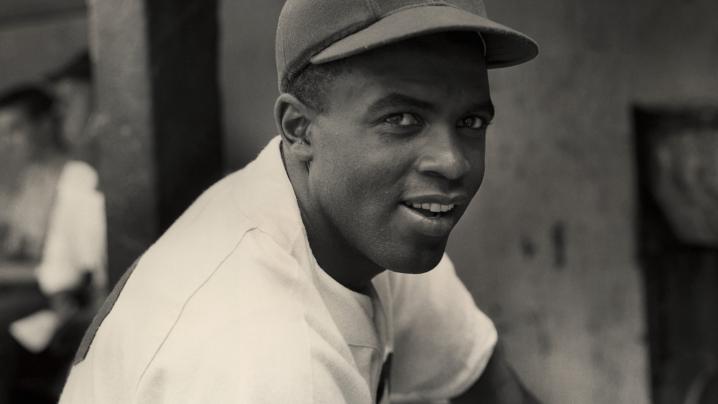

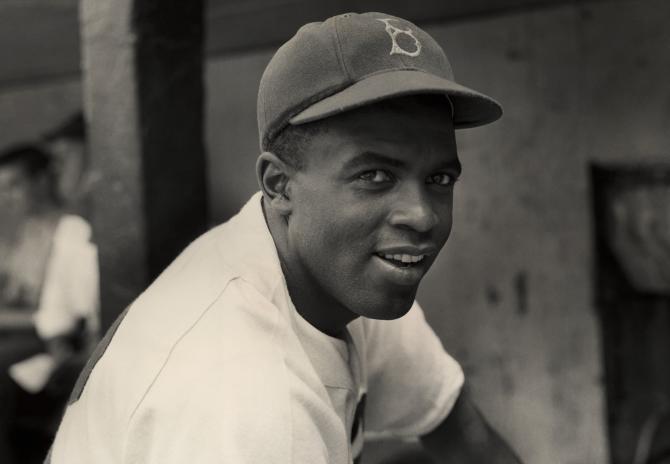

Jackie Robinson

Courtesy of Hulton Archive/Getty Images

It’s never too late to make amends, even 69 years after the fact. The Philadelphia City Council proved as much on March 31, when it unanimously passed a resolution honoring Jackie Robinson and officially apologizing for the treatment he endured while visiting in 1947, the year he broke Major League Baseball’s color line.

“Unfortunately in Philadelphia, Jackie Robinson experienced some of the most virulent racism and hate of his career,” Councilwoman Helen Gym said in introducing the action. “Our colleagues decided to introduce this resolution to celebrate Jackie Robinson.”

He has been celebrated many times before, most recently in 42, a 2013 movie starring Chadwick Boseman. Robinson is also honored each April 15—the anniversary of his major league debut—when every player and coach on every team wears his jersey number. And he certainly will be remembered fondly for generations to come, in recognition of his pioneering legacy that transcends sports.

But thanks to a new documentary from noted filmmaker Ken Burns, we’re able to see and appreciate Robinson in an entirely different light. This is no fictionalized script, such as in 42 or The Jackie Robinson Story, a 1950 movie starring the player as himself and Ruby Dee as his wife. In Jackie Robinson, a two-part film that airs Monday and Tuesday on PBS, Burns delivers the unvarnished truth that Hollywood treatments often whitewash.

He previously played myth-buster on Robinson’s tale in Baseball, a 1994 Emmy Award-winning nine-part documentary that attracted 41.3 million viewers to become the most watched miniseries in public television history. Robinson was an integral figure throughout the series, with a section devoted to him in eight of the nine episodes (Burns would release a 10th episode in 2010). When Robinson’s widow, Rachel, asked Burns to do a stand-alone project on her husband, the filmmaker was eager to comply.

“I’m glad we did this,” Burns said in a recent phone interview. “Earlier films were made using long-held myths and superficialities that we were happy to liberate him from. If we can free him from the tyranny of mythology he has become, he can be used as inspiration today, no matter what’s going on, including Black Lives Matter.”

Robinson was a helluva ballplayer, earning the Rookie of the Year Award in 1947 and being inducted into the Hall of Fame in 1962. But he was a soldier for civil rights more than anything else, fighting for African Americans’ equal treatment before and after his baseball career. The sport simply gave him a platform and opportunity to make history.

“Jackie Robinson is without question the most important person in the history of baseball, America’s most important sport,” Burns told The Root. “I also suggest he’s the most important person in the history of sports and one of the greatest Americans. When Jackie joined the Brooklyn Dodgers, Martin Luther King Jr. was in college. The military wasn’t integrated, there were no sit-ins and there was no Rosa Parks. He was a Freedom Rider before there were Freedom Rides, and we have to understand that issue.”

Through an impressive array of pictures, stirring original music by Wynton Marsalis and a lineup of interview subjects—including 93-year-old Rachel Robinson (who looks amazing and steals the show), President Barack Obama, Tom Brokaw, Harry Belafonte, historians, journalists and former teammates—Burns re-creates Robinson’s life and times in detailed fashion.

He came from a proud, strong family of sharecroppers who migrated from Cairo, Ga., to Pasadena, Calif., after his father deserted them in 1920. One of Robinson’s older brothers, Mack, finished second to Jesse Owens in the 200-meter at the 1936 Olympics in Berlin. Robinson attended UCLA and became the first athlete to letter in four varsity sports (baseball, basketball, football and track). He later entered the Army and faced a court-martial for refusing to move to the back of a bus. Robinson won the case and received an honorable discharge in 1944.

[ad_2]