[ad_1]

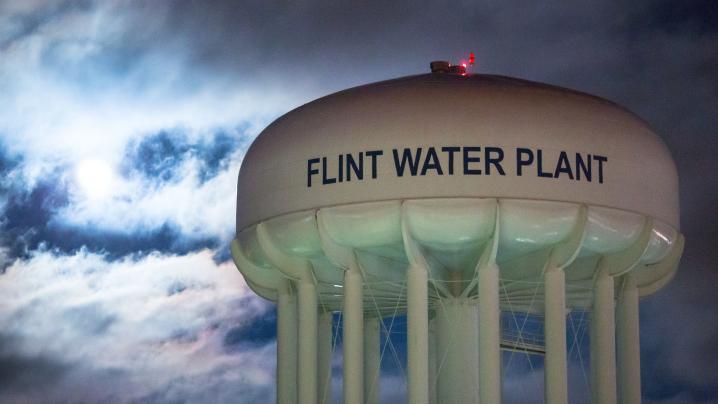

The City of Flint Water Plant is illuminated by moonlight on January 23, 2016 in Flint, Michigan. A federal state of emergency has been declared in Flint due to dangerous levels of contamination in the water supply.

Brett Carlsen/Getty Images

It’s easy to view the bubbling toxic water crisis in Flint, Michigan as yet another majority black city victimized by institutional neglect. Michigan itself is a cautionary tale on once thriving northern manufacturing towns, once the heart of black northern migration, now disintegrating from economic malaise.

But, in reality, Flint serves as primary example of what could become Black America’s most pressing problem in the 21st century: a failing infrastructure.

We all take hated potholes and cracked freeway bridges for granted. Yet, as dreary fact-of-life as infrastructure appears, it’s unavoidable as one of the most crucial quality-of-life issues for African Americans – if not the most crucial. Infrastructure is the nuts and bolt foundation of a city. Without it, societies can’t survive. If a city can’t keep itself together, then where will you live?

“Typically out of sight and out of mind, many pipes are more than a century old and are expected to need $1 trillion in repairs nationally over the next 25 years alone,” was Brookings’ Joseph Kane raising red flags about the infrastructure conundrum.

But race could define why, as Kane notes, governments keep the issue low key even as water pipe degradation and contamination crises in urban cores grow in frequency, exacerbated by rampant disregard for the plight of underserved or low income communities as occurred in Flint.

Black voters who are living it sense something’s wrong, as reflected in a July 2014 YouGov poll that gauged national attitudes on the issue. When asked if the federal government should spend more on infrastructure projects, a far greater share of black respondents (56 percent) said yes compared to whites (45 percent) and Latinos (40 percent). A 2015 AAA survey found an even larger gap between black and white sentiments on infrastructure investment.

And black Mayors have been sounding off on it, too, like Jackson, Mississippi’s Tony Yarber during a Mississippi Conference of Black Mayors summit last spring. When The Root caught up with him, Mayor Yarber explained a bleak situation of mass “infrastructure disinvestment.”

“Particularly, when we look at cities that have experienced white flight [like Flint], Yarber tells The Root. Disinvestment has taken the place of infrastructure stability. But when you look at predominantly white areas, or suburbs, that’s where the investment flows to for better streets, better roads, better water treatment systems.”

Yarber stresses infrastructure as the most basic function of government. As black populations are persistently concentrated in metropolitan cores (with trending “black flight” to suburbs creating rings of working and barely middle class pockets), infrastructure is also the top, yet most ignored black agenda item on tap. President Obama himself, with mixed success, raised it as a central element of post-recession national recovery. Remember the nearly forgotten American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, a.k.a. the $832 billion “stimulus package?” Pitching it as an ambitious, shy-of-$1 trillion anti-Depression fund, that was the Obama administration’s major public works play, a simultaneous push at job creation spurred by desperately needed infrastructure improvements.

Despite good intentions, and the hassle of Republican obstruction, the issue never took off for Black America beyond the limited promises of job creation. Jobs, of course, are a big part of it: infrastructure jobs account for over 11 percent of the workforce and, by 2022, will grow by 10 percent. That could put a huge dent in high black unemployment if governments funnel money where it’s needed.

But no one, including the president, framed it as the life-and-death matter that it is.

The greater the concentration of underserved communities, the greater lack of access to clean water resources – and, yes, in the United States. “There is a widespread assumption that safe, affordable water for drinking and household use is available to all residents in the United States,” notes Pacific Institute researcher Amy Vanderwerker in A Twenty First Century U.S. Water Policy. “The reality is that some low-income communities and communities of color lack access to water for the most basic human needs.”

Just take a quick look at the Environmental Protection Agency’s list of cities under federal consent decree for Clean Water Act violations and you’ll find a majority with populations that are a quarter or more black.

Nor is it confined to one-off crises easily contained once the water pipes are replaced, caulked and sealed. Devastating long term socio-economic and clinical consequences can linger for generations. ThinkProgress’ Carimah Jones demonstrates how developmental disabilities from lead poisoning in Flint will eventually overwhelm the city and state’s criminal justice system.

Quiet as it’s been kept, even low income neighborhoods in Washington, D.C. were gripped in a horrific lead poisoning crisis just a decade ago – but, because it’s the nation’s capital, we were either too cute or too diffident to make noise about it. A 2009 study on it obtained by The Washington Post “raised concerns about the 42,000 D.C. children, [ages 4 to 9 at the time of the report], who were in the womb or younger than 2 during the water crisis. Those children might be at risk of future health and behavioral problems linked to lead.” As Kevin Drum points out in this scary 2013 Mother Jones piece, lead levels have been linked to spikes in delinquent behavior.

Of course, in heavily gentrifying D.C., the lead crisis has become a distant memory. Professional whites are steadily moving in, folks of color are pushed out and the city bends over backward to accommodate new homes, refurbished old ones and the big fix of aging water pipes (because, God forbid, you can’t have that happening to white kids).

Flint then is just the tip of the lead-tainted iceberg. There’s a larger discussion on infrastructure failures exacerbated by institutional racism. Rampant disregard for the plight of underserved or low income communities isn’t an isolated thing.

And it gets worse when the city, heavily black and politically blue, is in a sea of political red. In Flint, it’s the majority black city with its black Democratic mayor and black Democratic state representative against the state’s detached white Republican governor and white Republican dominated state legislature unwilling. Michigan State Rep. Sheldon Neeley (D-Flint), who warned Gov. Rick Snyder (R-MI) a year before the crisis popped, told The Root that Snyder “hasn’t even reached out to me about the place where I live … where my family lives, where my mother lives.”

Political battles over infrastructure investments might seem remote and dry. But they are, for sure, some of the biggest and most impactful conflicts along race, geography and class. Many state legislatures led by consolidated and politically powerful pockets of exurban and suburban conservative lawmakers put up stiff resistance (“Urbanophobia” as Governing’s Alan Ehrenhalt pins it) against city prioritized mass transit and public works projects. Jackson’s Yarber points to his own case as he, and other black mayors in poverty stricken Mississippi, spar with a white Republican state government.

“As big as this issue is for African Americans, there is not one question about infrastructure in recent Democratic debates,” Peter Groff complains to The Root, a former president of the Colorado State Senate while representing the state’s largest pocket of black residents in Denver. “America’s grade on infrastructure is constantly below average, and that’s just on maintenance. We are failing on innovative approaches to keeping our people safe at home, on the roads, on rail and in the air.”

CHARLES D. ELLISON is a veteran political strategist and Contributing Editor to The Root. He is also Washington Correspondent for The Philadelphia Tribune, a frequent contributor to The Hill and the Weekly Washington Insider for WDAS-FM (Philadelphia). He is also Host of “The Ellison Report,” a weekly public affairs magazine broadcast and podcast on WEAA 88.9 FM (Baltimore). He can be reached @ellisonreport.

[ad_2]