The sound of the gritty plastic wheels of skateboards rolling on smooth cement echoes throughout Coleman Skate Park just below Chinatown in New York City. The park brims with skaters of all nationalities, including 19-year-old Brooklyn-born Duron. As Duron skates, he performs a “manual,” a trick where the skateboarder rides on the two back wheels of his board, one foot pushing down on the tail and the nose of the board in the air. Duron has high ambitions of one day turning pro and sees skateboarding as a chance to open new doors. I got the most grief from other brothers and sisters — from other blacks. Ray Barbee This melting pot scene at Coleman …

The sound of the gritty plastic wheels of skateboards rolling on smooth cement echoes throughout Coleman Skate Park just below Chinatown in New York City. The park brims with skaters of all nationalities, including 19-year-old Brooklyn-born Duron.

As Duron skates, he performs a “manual,” a trick where the skateboarder rides on the two back wheels of his board, one foot pushing down on the tail and the nose of the board in the air. Duron has high ambitions of one day turning pro and sees skateboarding as a chance to open new doors.

I got the most grief from other brothers and sisters — from other blacks.

Ray Barbee

This melting pot scene at Coleman Skate Park is emblematic of the world of professional skateboarding, where people of color are increasingly being welcomed by the industry and accepted in skateboarding communities. These days black skaters are visible in skateparks, suburbs and inner city streets from New York ;to New Orleans. ;

But diversity in skating wasn’t always the case. ;Pro-skateboarder Ray Barbee experienced the beginning of that cultural shift. In an interview with The Huffington Post, he said that it was a lack of access, mainly due to economic inequality, that kept skateboarding as a racially homogenous sport for decades.

In the fall of 1983, Barbee went back to middle school after spending the summer learning how to ride a skateboard in San Jose, California. He spent time after school shredding the backyard quarter pipe with a motley skateboarding crew and afterwards jammed in his friends’ punk rock band. Barbee had found a passion and a brotherhood, but he couldn’t escape the flack that came from being a black skater.

“I got the most grief from other brothers and sisters — ;from other blacks,” Barbee told HuffPost. “And they were always like, ‘Why are you trying to be white?’ And I was like, ‘I’m just riding a skateboard, I love what I’m doing — ;I hope you dig what what you’re doing.'” ;

Although culturally diverse skaters such as Barbee have gained more exposure since the ’80s, skateboarding started out as a white suburban activity. The sport has integrated over the last three decades as it’s more grown mainstream in popular culture. Black celebrities who also skate, such as Lil Wayne, Lupe Fiasco ;and Pharrell, have changed the assumption of who skaters can be and what they can look like through their presence in the extreme sports.

Skateboarding was pioneered by surfers, which, according to Barbee, was an economically stratified sport. The expenses needed to live near or travel to coastal cities and purchase surfboards and other costly equipment made the sport less inclusive to people of color. ;

“You think [about] the ’70s and the park era, and there’s definitely people of color that were skating in the parks,” Barbee said. “But again because the tone was set early on for the practitioners that got into skateboarding from surfing it became predominantly a white thing — that’s just the reality of it.”

In the ’70s, private investors built skateparks that mimicked the swimming pool skate bowls, but they didn’t last for long. “The skateboards and equipment people used at the time weren’t particularly safe and you ended up with a number of injuries,” said Miki Vuckovich, Executive Director for ;The Tony Hawk Foundation. ;Many of the skateparks shut down when private companies couldn’t support the cost of insurance, ushering in the backyard wooden ramp era ;when skaters built structures up to 12 feet wide at their homes. ;

“Again it’s accessibility,” Barbee said of the newer underground culture. “Now to skate a half-pipe you got to know the dude that owns the ramp. To have to a half-pipe your parents most likely had to have bought their home, have enough property to house a ramp and be able to pay for a ramp.”

While Barbee mentions not encountering discrimination directly from white skaters, he did experience instances of being uncomfortable with undertones of racist iconography in skating counterculture. “It was like everybody was into skateboarding and we indulged in all of the creative aspects of the culture whether it was playing music, making videos, you name it, that stayed pretty undiluted, if you will, that stayed pretty true, and I didn’t have to battle with racism in that aspect.”

According to Barbee, ;street skating ;in the early ’90s prompted a radical shift that opened the floodgate of diversity. Skateboarding rolled out of the backyards and literally into the streets as skaters realized that you didn’t need a ramp to skateboard or turn pro — all you needed was cement. Barbee actually started off as a vert skater, but after an injury kept him from skating ramps he decided to practice in the streets, eventually catching the attention of legendary skateboarder Stacy Peralta and turning pro in 1989.

The industry became more mainstream with the first X-Games in 1995, ;the first Tony Hawk pro skater video game in 1999, and the extreme sport cartoon Rocket Power, ;all of which popularized the sport in communities of color where access might be limited. ;These watershed moments in the sport made way for new pro-street skaters like Nike’s Theotis Beasley, Baker’s Cyril Jackson ;and former BET reality TV skater Terry Kennedy.

Kennedy, 29, ;grew up in Long Beach, California where it was difficult to find places to skate. “We just kept skating, pushing each other, meeting up and then eventually starting to progress,” Kennedy told HuffPost. “From there we ended up getting a skatepark in our city.”

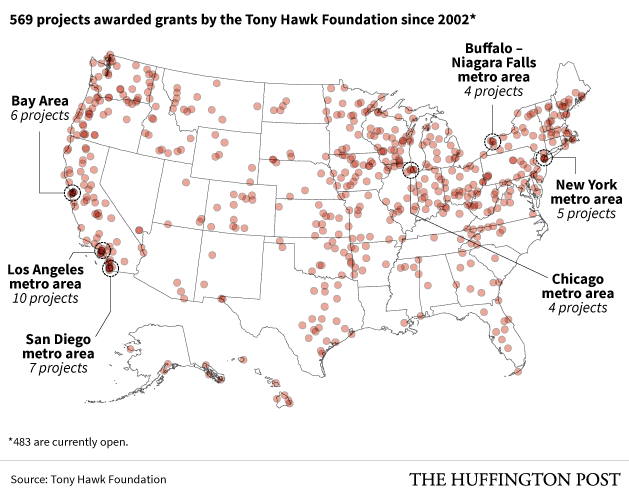

In the past decade, ;skateparks have resurfaced as publicly owned facilities like city ballfields or athletic courts. The Tony Hawk Foundation has been instrumental in building these establishments ;where youth can have a place to skate safely and legally for free, particularly in low income and marginalized neighborhoods.

“The Tony Hawk Foundation works with local advocates and city administrations to help them through some of [the] steps, and to make sure that they’re asking the right questions, and making the right decisions, and creating a good compelling skatepark that’s actually going to attract kids get them to use them,” Vuckovich told Huff Post. ;

“People of color are more prominent riding skateboards now,” Barbee said. “It’s clear that it’s no longer just a white thing.” ;

Also on HuffPost:

— This feed and its contents are the property of The Huffington Post, and use is subject to our terms. It may be used for personal consumption, but may not be distributed on a website.

Excerpt from: