[ad_1]

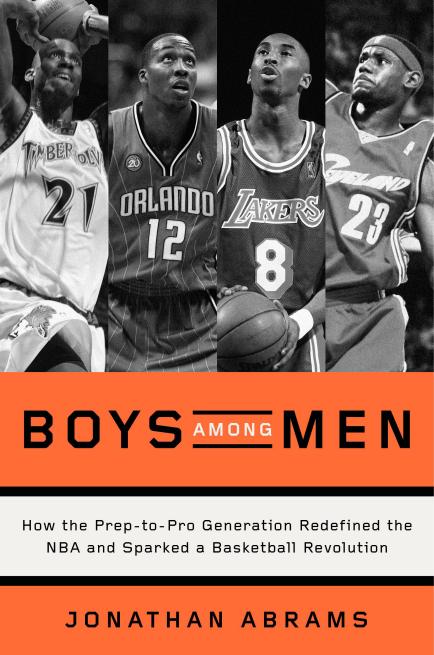

Boys Among Men book cover

Crown Archetype

Between 1995 and 2005, three of the greatest NBA players of all time—Kevin Garnett, Kobe Bryant and LeBron James—and several perennial all-stars, including Dwight Howard, Tracy McGrady and Tyson Chandler, were drafted straight out of high school. Unfortunately, that path wasn’t quite the yellow brick road that it seemed.

Others, like Ndudi Ebi, Korleone Young and Leon Smith, washed out of the NBA after barely getting a seat at the end of the bench. The latter trio was often cited when the NBA instituted an age limit just before the 2006 draft, which effectively closed the prep-to-pros pipeline. Instead, it created the one-and-done phenomenon in men’s college basketball under the NCAA, wherein top talents spend a year on campus before heading to the pros. The rule sparked a debate that rages to this day about its propriety and fairness.

Jonathan Abrams examines this era in his new book, Boys Among Men: How the Prep-to-Pro Generation Redefined the NBA and Sparked a Basketball Revolution. He takes a deep dive into the lives of those who prospered and those who floundered during that era. “They really bridged the gap,” he tells The Root of that era and his subjects. “The NBA was really trying to find itself after [Michael] Jordan retired from the [Chicago] Bulls.”

The book captures that era in glorious detail, focusing on the NBA’s struggle to find a new identity, especially one not defined by hip-hop culture, and goes in-depth into the players who made it and how they did it. For instance, Bryant was the 13th overall pick in the 1996 draft, and 20 years later, many of the 12 general managers who passed on him are still trying to explain their thinking. The book also offers wonderful portraits of the pioneers of this trend—Moses Malone, Bill Willoughby and Daryl Dawkins—each of whom made the leap from high school to the pros in the mid ’70s.

Abrams didn’t set out to become a basketball scribe. He grew up in Southern California and was an avid baseball fan. During his early days at the Los Angeles Times, he was able to cover a couple of baseball games and quickly discovered that it wasn’t for him because of the unpredictable length of the games, the lack of rapport with the players and the long days that beat reporters endure. He was able to land a spot at the paper covering the Los Angeles Clippers, and from there he went to the New York Times, where he wrote about basketball. In 2011 he went to Grantland, the now-shuttered ESPN sports-and-popular-culture site, where he began some of the research that led to the book.

Abrams says he embarked upon the project feeling that the age minimum was unfair, but as he delved deeper into the matter, he discovered that “there was a lot of gray area.” In particular, he was influenced by his interview with former NBA Commissioner David Stern, who lobbied for the rule’s inclusion in the league’s collective bargaining agreement with the NBA Players Association: “He said as an employer, why shouldn’t he have the right to specify the qualifications of his future employees?”

The author says he believes that the one-and-done rule doesn’t serve anyone’s interest. He proposes reopening the pipeline for high school stars to enter the draft, but if they choose college, they should be free to pursue the NBA after two years so that their game and life skills can mature. He cites Ben Simmons, widely regarded as the top prospect in the upcoming NBA draft, and his experience at Louisiana State University, from which he withdrew as soon as the basketball season was over. “His one year of collegiate experience didn’t help Simmons or LSU,” says Abrams.

The prep-to-pros era followed closely the first golden age of hip-hop, which diversified the avenues of economic aspiration in the African-American community. Abrams chronicles the resentment that some of these athletes faced from their peers. “Oh yeah, Tracy McGrady received a $12 million sneaker deal before he ever played a minute of NBA action; it made the guys who paid their dues angry,” he says. A few years later, James received a $90 million deal shortly before the NBA lottery, a clear sign that power had shifted from the veterans to the newcomers.

The harder issue lies in parsing what made K.G., Kobe and LeBron so different from the other enormously talented high schoolers who tried to make it in the NBA and failed to achieve greatness. “They were unique,” Abrams says. “They had a rare ability to really just focus on basketball and improving their game.”

Then, almost sympathetically, he recounts the circumstances that prep-to-pros-era players faced: “You’re young; your day is no longer as regimented as it was in high school and the pressures on your time are less than they’ve ever been. You’ve just been handed a bundle of money, too.” He pauses for a breath. “It amazes me that more of these players didn’t lose their marbles.”

[ad_2]