This piece was originally published on TakePart.com Ten years ago, the football team at O. Perry Walker High School in New Orleans was grinding confidently in the late-summer heat. The Chargers, as the team is known, had a deep bench of talented players and were led by a top-flight coaching staff, some of whom had worked at the college level. The team was viewed as a serious contender for Louisiana’s 2005 high school football championship–a significant point of pride for the school, which is nestled in a relatively hardscrabble neighborhood along the Mississippi River. Then, Hurricane Katrina barreled through New Orleans. Fragile …

This piece was originally published on TakePart.com

Ten years ago, the football team at O. Perry Walker High School in New Orleans was grinding confidently in the late-summer heat. The Chargers, as the team is known, had a deep bench of talented players and were led by a top-flight coaching staff, some of whom had worked at the college level. The team was viewed as a serious contender for Louisiana’s 2005 high school football championship–a significant point of pride for the school, which is nestled in a relatively hardscrabble neighborhood along the Mississippi River.

Then, Hurricane Katrina barreled through New Orleans. Fragile levees burst and sent floodwater across nearly 80 percent of the city. The catastrophe triggered the largest and most rapid human migration in North American history: More than 350,000 New Orleanians fled the region by car before the storm, and another 100,000 boarded buses and planes, bound for points across the United States. About one-quarter of those who left were children. The players and coaches of Walker (which is now known as L.B. Landry-O.P. Walker College and Preparatory High School) landed in Milwaukee and Atlanta, Los Angeles and Houston, and formed a remarkable sliver of the Katrina diaspora.

In the chaotic days after Katrina, the school’s coaches and players had no way of communicating. New Orleans’ main telephone network equipment flooded, making it nearly impossible to reach anyone who had a cell phone number with the city’s 504 area code. Social media was in its infancy: There was no Facebook for non-college students, no Twitter, and no Instagram.

It’s now commonly understood that a good share of New Orleans’ evacuee children endured high levels of hostility in the hallways of their new schools, especially if they landed in cities such as Houston and Atlanta, which were teeming with evacuees. Most missed months–even years–of school.

A researcher studying resilience in the 2005 Walker team would conclude, understandably, that football was not only their passion–it was a protective force. The researcher would find some key ways the Walker team is an important anomaly in the Katrina diaspora. Many evacuee children were viewed as a burden by school staff and local officials. After Katrina, however, coaches across the Gulf Coast quietly bucked high school recruiting rules and courted talented football players. Players from Walker–a known powerhouse in New Orleans–were welcomed by schools when they arrived.

It was also football season, so the Walker players were motivated to quickly reenroll in school and determined to stay in one place, partly because of their passion for the gridiron. So their post-Katrina schooling was much more stable than that of other evacuee children, many of whom moved several times to reunite with family members. Players’ families also benefited from this unexpected protective force: Given the uncertainty of the time, some New Orleans players were glad to land at schools that also secured housing for their families–and, in some cases, even arranged jobs for parents.

National sports reporters who tracked Katrina-displaced players invariably wrote about that year’s star Walker player, Kendrick Lewis, who was considered one of America’s best high school wide receivers. By the time Katrina struck, Lewis had committed to the University of Mississippi’s football team. He moved to Atlanta after his mother found a public housing apartment within a bus ride from Gainesville High School, where he became an overnight sensation. He now plays for the Baltimore Ravens. “Being an athlete that somebody wanted on their team meant these kids were able to provide for their families,” says Corey McCloud, who was one of Walker’s football coaches at the time.

In the world of sports, bonds between football standouts and their coaches are endlessly discussed. But the role that McCloud and another coach, Donald Cox, filled in their players’ lives after Katrina has been unusual. It gave Walker’s players yet another surprising advantage over other evacuees: an extra set of adults committed to their success, especially in the aftermath of catastrophe.

McCloud evacuated to a cousin’s apartment in Atlanta and was swiftly hired as a coach at Westlake High School. Within a few weeks of the evacuation, McCloud and his two roommates in Atlanta had taken in two Walker football players whose families had been displaced elsewhere. The boys’ parents visited and were supportive but chose to give their sons stability in the wake of the storm by allowing them to live with three “big brothers” and play football under McCloud at Westlake for the year.

Despite the advantages Walker’s players had over some evacuees, they still struggled deeply and suffered dashed dreams and disappointments because of Katrina-prompted relocations and instability. A decade later, a core group of Walker players and coaches who saw each other as fathers, sons, and brothers talk about the deep bonds they shared and how that got them through their time spent in the Katrina diaspora.

Here are their stories. The coach and the player who treated each other like father and son–until Katrina separated them overnight. The player who felt sure he was headed to the National Football League. The young player who became a two-time collegiate All-American and then put on his snow boots and played professional football in a small town in Minnesota for several months. The kindhearted coach who served as a connection to New Orleans for all Katrina-displaced students in his school–and, for his players, was always just a phone call away.

Derek Rose, 25. Football coach. New Orleans Recreation Development Commission. New Orleans

In August 2005, Derek Rose was hyped up for a football jamboree in New Orleans. He was only a sophomore, but he’d been chosen to be a starting linebacker on O. Perry Walker’s football team because of his tackling ability. No one got by him. “I was ready,” he recalls.

When Rose and his teammates showed up for the Saturday-morning jamboree, they learned it had been canceled because Hurricane Katrina was looming in the Gulf of Mexico. On the following morning, Aug. 28, New Orleans Mayor Ray Nagin issued the city’s first-ever mandatory evacuation order. “We’re facing the storm most of us have feared,” Nagin said, warning residents that the storm’s surge “most likely will topple our levee system.”

Rose stuffed a bag with a few T-shirts and shorts, expecting that he’d be back at football practice in two days, maybe three. That was typical when hurricanes threatened. His bag included nothing football-related except his Nintendo PlayStation 2 and a specially altered Chargers version of the video game NCAA 2005.

Even as the Rose family drove out of town, his team was oddly within reach: At one point, while they sat in gridlock traffic, he saw a teammate, Kendrick Lewis, in a nearby car. The family found its way to a relative’s house in College Park, Georgia, 20 minutes south of Atlanta. The family was relieved to watch initial television news reports that New Orleans had emerged unscathed by Katrina. Soon, however, came bleak images: Some of New Orleans’ levees had burst, drowning the city and leaving thousands of people pleading to be rescued as conditions worsened. “This is real,” Rose recalls thinking as he watched the chaos unfold. “I may not be going home. I’ll have to start a whole new life.”

Rose’s parents enrolled him in the school closest to his aunt’s house, North Clayton High School. Though he heard about brawls between New Orleans evacuee children and students in Houston–one of which was televised on CNN–his school was relatively quiet.

All Rose wanted to do was get back to the football field. On the field, he wouldn’t have to think about relatives whose whereabouts weren’t yet known. He wouldn’t have to hear his parents on the phone, trying to get assistance from the Federal Emergency Management Agency. He wouldn’t have to trudge along to their visits to the Red Cross centers to sign up for further assistance and to look through used clothes. At his aunt’s three-bedroom suburban home, Rose slept on the couch and a cousin slept on a pallet of blankets on the floor. So the football field was an escape, the only place where life seemed normal.

He immediately began to play junior varsity at North Clayton, but like most of his Walker teammates, he couldn’t play varsity ball until the state athletic board cleared him, which took a few more weeks. Once he got to the varsity level, he tried to adjust. His new teammates were friendly–but, he says, “I don’t think they wanted to get too close. They pretty much knew I was going to go back home.” Also, North Clayton’s football team already had a strong linebacker, so Rose couldn’t start at his position. “I used to get down about not playing football,” he recalls.

When Rose got depressed, he’d look to his New Orleans teammates. “I’d hear about Eldric dominating in Houston, or Kendrick making plays in Gainesville. They were representing O. Perry Walker the right way,” he says. “It made me feel good.”

After a month or so, Rose called Corey McCloud’s old 504 telephone number, and to his relief, his favorite coach answered. At Walker, McCloud had pushed Rose on the field and in the classroom. McCloud and Rose had both kept their original numbers, a rarity that allowed them to reconnect after weeks of not talking. After that, once or twice a week, Rose called McCloud, who kept his spirits up.

In Atlanta, Rose hoped to transfer to Westlake so he could play for McCloud. The two were so close, Rose wore a football jersey that bore the number 57–the same number McCloud had worn in high school. “I looked at him like a second father,” Rose says, adding, “I really missed being around him.”

Rose’s father found a job at the Atlanta airport, and would have let his son stay in Atlanta and transfer to Westlake for junior year. But Rose’s mother, a social worker, had been called back to New Orleans for work and wanted their son there. Rose moved back with his mother and reenrolled at Walker for the 2006 fall semester. Now Rose understands his mother’s rationale: His grades were slipping, and she wanted to check his homework and enforce curfew. “She wanted to be more hands-on,” he says, “and she wasn’t ready for me to leave the nest.”

Not long before leaving North Clayton, Rose broke his ankle during springtime football drills. Back in New Orleans, he found that few doctors had returned, so it was hard to find suitable rehabilitation. As a result, he sat out most of his junior year at Walker.

But by senior year, he’d returned to the team, and he was a standout player. Rose earned a football scholarship to Northwestern State University in Natchitoches, Louisiana, where he became a two-time All-American athlete, shattering records. He was pushed by another player from Walker, Eldric Cambrice. Cambrice warned him to focus on academics. It paid off: In 2012, Rose graduated with a bachelor’s degree in criminal justice. For six months, he played with an Indoor Football League franchise in Bemidji, a town in northern Minnesota. “I got my full snow experience,” Rose says, recalling wintry drifts two feet high. In the end, he decided the IFL was not for him. He moved back to New Orleans in 2013.

Rose thinks back to his arrival at Northwestern State, after not seeing Cambrice for three years. “But once we talked with each other, the love was still there,” Rose said. “We’ll always have that bond. It’s family.”

Corey McCloud, 40. Football coach. McDonogh 35 High School. New Orleans

Nearly every night after Hurricane Katrina, Corey McCloud talked by phone with some of his former Walker players. Two players were staying with him in a three-bedroom house owned by an Atlanta teammate’s father, so the players would often throw him the phone after they were done speaking with a former teammate displaced in Texas or South Carolina or Wisconsin. Sometimes he’d hear about new coaches or girls. Often, they just wanted someone to tell them that everything would be all right.

McCloud had gone to college on a football scholarship. But he quit the game after graduation and worked in the accounting department of a prestigious New Orleans business-law firm. Then, a few of his college teammates convinced him to follow his convictions and become a high school coach. “My whole motivation was to show young black men that there was more to life than the inner city of New Orleans,” he says. “I know from experience that football can take you to college–and help you see the world.” For some of his New Orleans players, expanding horizons meant as little as showing them how to order at a sit-down restaurant, or traveling across the state line for the first time to a tournament in Georgia.

After Katrina, McCloud hated to hear how their potential had been narrowed–how a few of his starters had been demoted to junior-varsity-level play or ordered to sit out four games because of “eligibility” reasons that didn’t seem to make sense. For most of his players’ careers, McCloud had been the person who helped make things right on the field. Suddenly he had no control. “It was tough. You felt helpless,” he recalls of the months after the storm. “Guys we knew so well were not getting a fair shake.”

McCloud sympathized with coaches who had to reconfigure their line-ups to make room for a guy who’d evacuated from New Orleans. In some cases, that meant benching players who’d been on teams for years. “This Katrina thing was new to all of us,” McCloud says. “There was no blueprint.”

McCloud and two friends had evacuated to the Atlanta apartment of his cousin, a flight attendant, who took her New Orleans guests to a barbecue on Labor Day weekend. There, a substitute teacher from nearby Westlake High School told him that the school had a strong football team. He recalls saying, “Tell your coach that I got some players who need a home.” A few minutes later, she walked up to him with her cell phone and said, “It’s the head coach.” The two talked, and McCloud agreed to attend a practice on Labor Day.

On Monday, Labor Day, McCloud came to the field and walked around with the head coach, who asked him to run some linebacker drills, his specialty. A feeling came over him, and he ran drills like he’d never run them before. “Everything, Katrina and all we’d been through, was just gone for those two minutes. I just lost myself emotionally,” McCloud remembers.

As they walked off the field that day, the coach asked him, “Coming back tomorrow?”

That continued for 10 days, until the day before Westlake’s next game. “I want you coaching on this staff,” the coach said. McCloud took the job. Led by Westlake quarterback Cam Newton (who now plays for the Carolina Panthers), the team–whose ranks had been bolstered by McCloud’s former players from Walker–went on to win all but two games. They made the play-offs but lost in the third round to Gainesville, Kendrick Lewis’ team.

At Westlake, which is about 20 minutes southwest of Atlanta, the student body was all black, but family income levels were more varied than at Walker, where almost all the kids were low-income. “Westlake had kids that came from nothing and kids who lived in million-dollar homes,” recalls McCloud, who soon joined the school staff as a behavior interventionist. He embraced his job and immediately began to iron out friction between Westlake’s original students and the dozens of New Orleans children who’d landed there. Some of the students started fights for typical teenage reasons, such as seeing a boyfriend or girlfriend flirt with a New Orleans arrival. Other fights began because an Atlanta student called an evacuee a “refugee” or–thanks to television news coverage of looting in New Orleans–crudely suggested that New Orleans students should probably be watched more carefully.

Throughout the year, the school’s office manager would frequently request McCloud’s assistance over the school’s public address system: “Coach McCloud, come see about your people.” The term “your people” meant students from New Orleans. He’d often find New Orleans students who were exhausted and stressed out. So he’d pull them aside. “One day, we’d talk about something our grandmothers used to cook”–like Patton’s hot sausage, filé gumbo, or stuffed green bell peppers–“or about music, about second lines,” he recalls. “The kids were on edge, so I tried to be that comforting person.”

One night, eating wings at a sports bar, some coaches from Westlake’s rival, Tri-Cities High School, told him they, too, had hired a coach from New Orleans. “And you know what?” one of the coaches said. “You sound alike.” They described their newly hired coach as chanting and frequently doing push-ups and squats alongside players. McCloud knew he’d finally found coach Donald Cox, who was known for leading players in chants during practice. Soon the two were back to normal, talking often and comparing notes.

Later, McCloud became a sounding board for Walker player Darren Hunter at Savannah State University, where he worked after coaching at Westlake for a few years. He moved on from Savannah to a series of other coaching positions at the college and professional levels before taking a coaching job in New Orleans in 2013 at McDonogh 35 High School, his alma mater. He moved home, bought a house in the city’s Gentilly area, and plugged back into the high school sports scene.

Today, as McCloud looks back at his 2005 team, he wonders what might have been. “Imagine if we could’ve gotten all of them on the field,” he says.

Ten years ago, that was the question of the year for McCloud as he talked on the phone with his players. “It always came back to ‘Would your team now beat the 2005 Walker team, if it was together?’ ” The answer was always the same: “Nah, they’re not that good, coach.”

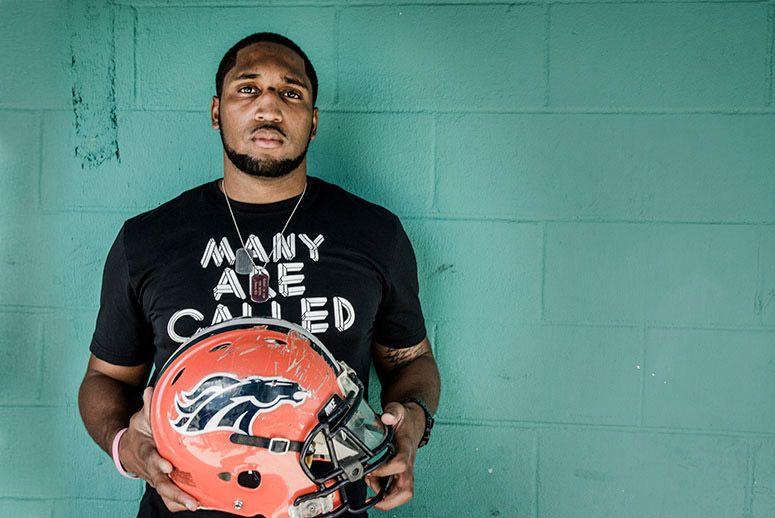

Eldric Cambrice, 28. Behavioral interventionist and football coach. L.B. Landry-O.P. Walker College and Career Preparatory High School. New Orleans

Eldric Cambrice was aiming for the top. He wanted high school numbers that looked good enough to attract college scouts, a full scholarship, and a ticket to the NFL. That occupied his mind most of the time he played cornerback and safety on O. Perry Walker’s football team. “I even used to work on my autograph. I was in deep with it,” he says, writing a capital E with a flourish.

After Katrina, his family–mom, dad, and siblings–were displaced from their quiet New Orleans neighborhood, Algiers Point, which borders the river across from the French Quarter. They landed in Houston, where he enrolled at Westbury High School. Soon, he became a go-to player on Westbury’s varsity football team, returning punts and playing cornerback and filling holes wherever else the team needed him. His brief stint on the junior varsity team was laughably short: In one game, he scored six touchdowns, and he was swiftly given a permanent spot on the varsity team. By late fall, he’d helped Westbury reach the play-offs.

But things at Westbury were tough for some Katrina evacuees. It was the site of a brawl so terrible that it made national headlines. The incident started as a verbal argument in the cafeteria between two girls, one from Houston and one from New Orleans’ Ninth Ward. Then, as other people joined in, the fight became physical, moving down the hallway and outside. Cambrice recalls seeing nearly a dozen Houston guys punching a young man from the Lower Ninth Ward on the blacktop outside the cafeteria’s door. Overhead, a CNN helicopter hovered, recording the blows.

Cambrice, watching from the other side of the cafeteria, thought seriously about jumping into the fray and helping his fellow New Orleans student. But his coaches and teammates pulled him away. “It was still football season,” he says, “and they didn’t want anything to happen to me.”

Originally, right after Katrina, Cambrice heard that one of his closest New Orleans friends, Kendrick Lewis, was in Georgia, and he wanted to head there. But his parents insisted he stay in Houston. That seemed like the right decision as Cambrice tore up the field in Houston and scouts from top colleges began to notice him. But then, halfway into the season, Cambrice’s mom told him that she and his father were ready to move back to New Orleans and work on their flood-damaged house. The next day, he told his coaches. “They went berserk,” he recalls. He was able to stay in Houston after a teammate’s mother asked Cambrice to stay with her family. She treated him like a second son–to the point where he drove the family car. She also paid for tutors for the young men before they took their ACTs. He ended the season at Westbury on a high note.

Then things started to fall apart. Somehow, Cambrice lacked a world-geography class with a Louisiana credit. Texas and Louisiana classes have different class hours attached to each credit, making the credits utterly incompatible, a problem that many students experienced after Katrina. He knew the Walker office would figure it out for him. The only way for him to make up his credit and graduate on time was to move back to New Orleans.

He arrived back in New Orleans in January, still with high hopes. But once he returned, most of the college scouts quit following him. He received two full scholarship offers, one from the University of Houston and the other from Northwestern State University in Natchitoches, Louisiana. He chose Northwestern State.

Not long after he started play at Northwestern State, the NCAA flagged his high ACT score–earned in Houston after intensive tutoring–because it was more than three points above an earlier result. He retook the test but didn’t do as well, was placed on academic probation, and lost his financial aid.

Cambrice began to work long hours to pay tuition. The loss of aid was a setback. Even worse, he realized that a professional football career was no longer a possibility. “I had been playing football since the age of five. That’s all I knew,” he says. “When it didn’t come through, I wondered, ‘What’s plan B?’ “

He was still about a year short of a degree, but he called Walker. When he graduated in 2006, the principal, Mary Laurie, told him there would always be a place for him at the school. In September 2011, she brought him onto her staff as a behavioral interventionist. He now lives in Algiers with his wife and their three children, works days at Walker, and also coaches the football team’s wide receivers. He hopes to return to college next year to get his diploma.

“I think Katrina sidetracked Eldric because he didn’t have us around, pushing him, reminding him to do the little things,” says coach Donald Cox, who is impressed by what he sees in his former player as a coach. “Eldric is mentoring tougher kids than we had to mentor. He is an outstanding high school coach, and he will be a great head coach because he has a tremendous good in his heart.”

Cambrice hears Cox’s analysis and nods. For instance, Walker staff would have recognized that he’d be flagged for the difference in his two ACT scores, he said. They would have known that his schedule lacked a world-geography class. And they would have encouraged him through his hardships. “I did bounce back, and I had a good season my senior year,” he says. “But it was nothing like playing your senior year at home and having that senior-year experience.”

Donald Cox, 46. Football coach. John Ehret High School. Marrero, Louisiana

Darren Hunter, 25. U.S. Army National Guard recruiter. Atlanta

When Darren Hunter was a freshman at O. Perry Walker, coach Donald Cox took him under his wing. “Anytime I asked about anything, he was there,” Hunter recalls. “He was the one who taught me to drive. He let me drive his car most times.”

Cox says he’d given Hunter a ride home one night after practice and realized they lived near each other. Cox also realized that Hunter’s dad wasn’t in his life. “Darren was a very quiet young man,” he says. “He had a nice mom, a nice family. He was also really smart, a 4.0 grade average.”

Cox had no children at the time. The two developed a father-son relationship. He called Hunter “Son.” Hunter called him “Pops.”

Then came Katrina, and the two lost contact for nearly a year.

In the days after the storm, a friend referred Cox to Tri-Cities High School in East Point, in southwest Atlanta. Though Cox didn’t know it at the time, Hunter had settled with his family in Chamblee, in northeast Atlanta, where he was attending Chamblee Charter High School, “an outstanding school,” Cox says.

Cox found his players at Tri-Cities to be calmer, he says. “Tri-Cities was more of a middle-class area,” he said. The school, though in the inner city, specialized in arts and performance. “The kids still needed guidance. But they weren’t as angry as New Orleans kids were,” Cox says, noting that the football team was decent, though nothing like Walker’s.

In the spring of that year, Cox took a health-certification class at Chamblee Charter High School. As he walked through the school hallway, Hunter came down the steps. “Son!” Cox recalls saying. He describes it as “the happiest day.”

“It was the greatest moment to know where he was at,” Cox says. “It was instant tears. I think we must have hugged for about five minutes. It felt like it was god-sent for Darren and me to be in touch with each other.”

Within a week or two, Hunter and his mother had found a new apartment near Tri-Cities so that he could attend school there. “It shocked me how fast that happened,” Cox says. “His mom told me, ‘I wanted him to finish up his senior year along with you.’ “

Hunter settled in, content to be back in the same place with his pops. For his part, Cox was ecstatic. “We had lost so many guys, and we lost our school,” he says. “But Darren was one of the most outstanding young men I have ever coached. He was more than a player to me. And having the chance to coach him senior year was one of the greatest blessings ever.”

Cox coached at a series of other schools before moving back home. Though he and his wife had separated, they reunited after Katrina and now live in Algiers with their young son. “We found our way back to each other,” he said, noting that for him, the storm clarified what was important in life. “It made you understand that life was not always about playing ball. Because in the blink of an eye, everything can change,” he says.

Hunter got a four-year scholarship to Savannah State University, where he was coached by Corey McCloud. Hunter graduated cum laude with a bachelor’s degree in criminal justice. But all through college, he would often seek out McCloud, who would talk him through whatever he had on his mind.

Hunter still keeps in close touch with Cox and gets sentimental as he talks about times on the Walker field. As a coach, Cox would get on the field with his players, running drills with them, lifting weights alongside them. And then he had his chants. “It took the nervous tension out of the kids. I made up a lot of chants, to get the kids hyped up,” he says.

One chant in particular stuck out among the players, who recall saying it every day at practice: “Am I my brother’s keeper? Yes, I am.”

Cox’s rationale for the chant was simple. “Sometimes kids are so caught up with themselves,” he says. “It’s a way of getting the kids to understand, you need to ask, ‘How can I help somebody else out?’ “

Hunter remembers this well: “The chant itself, it means, ‘Take care of the person next to you. No matter what happens, take care of them.’ “

For the coaches and players from the tossed-and-turned Walker team of 2005, the sentiment holds especially true, Hunter says. “We embodied that.”

Visit TakePart.com for more on Project Katrina.

— This feed and its contents are the property of The Huffington Post, and use is subject to our terms. It may be used for personal consumption, but may not be distributed on a website.

See the original post –

Brothers’ Keepers: How the Walker High Football Team Survived Katrina–and Its Aftermath