[ad_1]

My grandmother had a morning ritual: She’d wake up around 6 a.m.; have some variation of coffee, crackers and sausage for breakfast; and then watch the Channel 4 news. Later, she would drive to the gas station for a few scratch-off tickets and to pick her lottery numbers. She’d always take the service road because she was afraid to drive the Dallas, Texas, freeways.

When I was in my late teens, I received a call from her in a state of panic. She was unsure where she was and knew nothing except that she’d parked in a parking lot. We were somehow able to get her home, but my family and I began to “watch her” after that incident.

In our minds, we were doing it to make sure she was safe. But looking back, I worry the loss of her independence ― her ability to do things like make herself coffee and go to the store ― broke her heart.

My grandmother encouraged me to see the sky as the limit of my dreams ― I credit much of my boldness to her. She could steal your heart but would get you right if you crossed her.

It was hard to learn about her diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. At the time, I was taking a psychology course and we were learning about the effects of dementia on the brain. I would share the information with her after class. I would also write her letters and try to explain what I knew and I’d always finish with “you’re going to be okay.” I told her “you’re not crazy or stupid” more times than I could count.

She was scared and so was I. Alzheimer’s and other dementia-related conditions are particularly terrifying because there is no course of treatment available ― no cure or even a method of slowing the disease’s progression.

During visits to my grandmother’s house, I would play her Sam Cooke songs and her favorite gospel music. I’d get false hope when she would remember lyrics. Within a few years my strong-willed, independent grandmother was unrecognizable and bedridden. I watched her fight until the end.

Alzheimer’s is the sixth leading cause of death in the country and it’s estimated that every 66 seconds someone develops the disease in the United States, according to the Alzheimer’s Association. More than five million Americans currently have Alzheimer’s and that figure is expected to jump as high as 16 million by 2050.

But not all Americans have the same risk level ― nearly two-thirds of those with Alzheimer’s are women, according to the Alzheimer’s Association. And black Americans are twice as likely as their white counterparts to develop Alzheimer’s and dementia. As a black woman, my grandmother was at greater risk due to multiple factors.

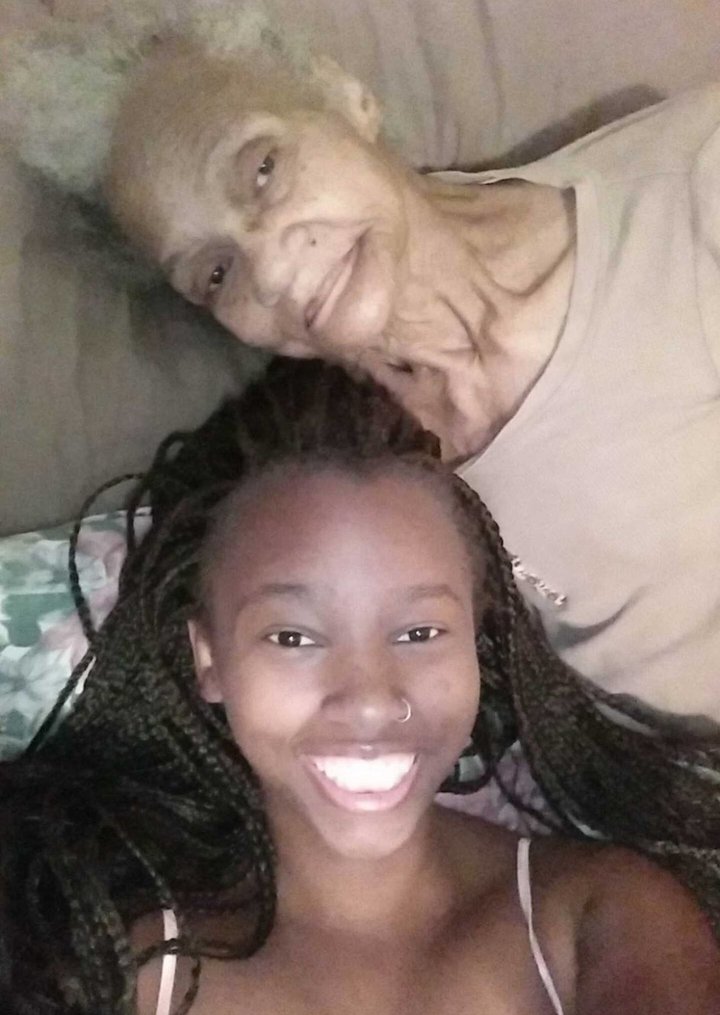

Courtesy of Rochaun Meadows-Fernandez

Hardly a new phenomenon in the community, variations of the term Alzheimer’s can be heard in colloquial expressions, like “old-timers” and “all-timers” among elders in the black community.

Black Americans are disproportionately affected by Alzheimer’s for some of the same reasons other health problems are more prevalent in their communities: A history of systemic discrimination has amplified poverty, hindered access to education and health care and left a legacy of physical and mental stress. These three factors contribute to a constellation of health problems, according to an analysis from RTi Research.

While doctors don’t have the full picture, it’s well established that risk factors for dementia include high blood pressure and diabetes ― two conditions that plague black Americans at a rate far higher than other groups.

Recent data suggests that black Americans are more likely to develop dementia if they are born in the “stroke belt,” a band of southern U.S. states with high stroke mortality rates, which includes Louisiana, Mississippi, Oklahoma, and Tennessee.

While all Americans who live in the stroke belt have higher rates of dementia, black Americans are 10 times as likely to live in this region than their white counterparts.

Racial bias in health care contributes to worse outcomes for black patients, including a lack of quality medical care. This history of this phenomenon often leads to a heightened distrust of doctors in black communities. This last issue in particular can contribute to later diagnoses in black Americans, which in turn affects their treatment. Though there is no cure for Alzheimer’s, catching it early can improve the life quality of the individual.

Not all is lost, though: Increasingly, organizations ― like the Purple Power Champions initiative in Colorado ― are working to reach out specifically to older black Americans for Alzheimer’s screening and prevention. But we could all do our part.

Black families need to prioritize health conversations, and the nation as a whole needs to better prioritize the consequences of systemic injustice. Perhaps if health were a bigger discussion prior to the loss of my grandmother, we could have extended our time together. I will never know. But among the lessons she taught me, I take with me the importance of fighting to reduce the stigma related to health problems like hers. If we talk about them, we can find a way to fight them.

[ad_2]

Source link