The more things change, the more things stay the same. Fifty years ago this month marks the uprising in the Watts community of Los Angeles, California in 1965. Spurred by the kind of tense police encounters that minorities fear but that have been a feature of urban American life, the upheaval in Watts demonstrates the utility and futility of urban protest. The Watts uprising illustrates how unforseen setbacks often saddle racial progress. The aftermath offers instructive insights on how activists might craft short-term and long-term visions of justice that can avert the trends of racial progress and relapse. What was the Watts Uprising? On August 6, 1965, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act into law. The law …

The more things change, the more things stay the same. Fifty years ago this month marks the uprising in the Watts community of Los Angeles, California in 1965. Spurred by the kind of tense police encounters that minorities fear but that have been a feature of urban American life, the upheaval in Watts demonstrates the utility and futility of urban protest. The Watts uprising illustrates how unforseen setbacks often saddle racial progress. The aftermath offers instructive insights on how activists might craft short-term and long-term visions of justice that can avert the trends of racial progress and relapse.

What was the Watts Uprising?

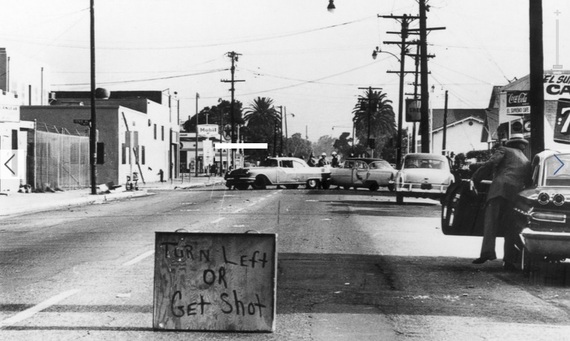

On August 6, 1965, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act into law. The law (which was disemboweled by the Supreme Court in 2012 and has few signs of being restored) was one of the feathers in the cap of the Civil Rights Movement. A week later, a white police officer, Lee Minkus, stopped a black driver, Marquette Frye, in Watts (a predominantly African American community) for reckless driving. Frye’s mother, Rena Frye, lived close to the place of arrest and came to retrieve the car and scold her son.

Stories diverge from here. According to Marquette Frye, he was hit over the head by one cop. An officer also twisted Ms. Frye’s arm behind her back in an attempt to arrest her and caused her to cry out in pain. According to Minkus, the 49-year-old mother agitated the situation by jumping on his back after the allegedly drunk Frye yelled at him “go ahead, kill me.” This all occurred in the view of about 500 people.

Since we are devoid of the kind of camera footage that is increasingly documenting police deception, what really happened will always be up for debate. Regardless of what precipitated the arrest, rumors circulated that police beat a pregnant woman and chaos ensued. The result was one of the largest riots in American history, with 34 casualties and $40 million in damage after a week of upheaval. The Watts uprising is especially significant because it bucked the social movement strategy of non-violence that was in vogue at the time and received unprecedented media coverage.

There were smaller protests in Philadelphia, Rochester, and New York a year before Watts, but these previous upheavals paled in comparison to Watts in death-count and property damage. The events in Watts were a break from how “race riots” traditionally operated. Historically, such riots often involved white attacks on black communities (e.g. Atlanta in 1906, Springfield in 1908, Elaine, Knoxville, Chicago, and Omaha in 1919, Tulsa in 1921, to name a few). After Watts, blacks began to turn their anger toward white-owned businesses in their segregated neighborhoods and occasionally toward innocent whites who were at the wrong place at the wrong time. Civil rights activist Bayard Rustin put it best when he claimed, “the whole point of the outbreak in Watts was that it marked the first major rebellion of Negroes against their own masochism and was carried on with the express purpose of asserting that they would no longer quietly submit to the deprivation of slum life.”

There were existing cultures of armed black resistance in North Carolina, Mississippi, and Louisiana. But these forms of black retaliation did not receive the kind of media scrutiny as the Watts uprising–a scrutiny that was only intensified by the advent of helicopter coverage of the upheaval. Watts was different. It cultivated an ethos of armed militancy that partly inspired organizations like the Black Panther Party, the Brown Berets, and the Young Lords.

These days cities have developed strategies to attenuate the possibility of large-scale uprisings like Watts by militarizing their police forces and incorporating racial minorities across sectors of government. To be sure, these strategies were learned primarily from Watts as well as the various urban upheavals of 1967 and 1968. Nevertheless, determined activists have demonstrated in Baltimore and Ferguson that they have no problem continuing the urban protest tradition that existed before and beyond Watts, albeit with refined tactics.

(F)utility and Change

Accordingly, the Watts uprising is significant for one more enduring reason. It shows that in some instances, urban protest can simultaneously work and be unproductive. Historian Gerald Horne, author of the authoritative book on the events in Watts notes, “uprisings like those in Watts are akin to a toothache in that they alert the body politic that something is dangerously awry. Their dramatic nature…can motivate sweeping social reform and/or repression.”

When a Watts resident was questioned about how the community benefitted from the upheaval, the man responded, “we won because we made the whole world pay attention to us. The police chief never came here before; the mayor always stayed uptown. We made them come.” He was correct. Contrary to one author’s recent insistence in Time that these riots “did nothing for black America, government did respond (although the quality of their response is a separate matter). Before the riots, then-mayor Sam Yorty ignored racial inequality in the city and stubbornly prevented federal War on Poverty funds from being distributed to poor communities in LA. After the upheaval, funds magically appeared for black and Latino community action programs across the city.

Soon thereafter, police brutality and chronic unemployment–issues that multiracial coalitions of activists complained about for years–suddenly received more scrutiny from politicians and academics. For decades, black doctors pleaded with the federal government for a hospital in the medical desert that was Watts, but to no avail. After the riots, local, state, and federal governments cobbled together funds to establish a much-needed hospital and medical school, which created jobs for blue-collar and white-collar minority professionals.

In 1973, the city even elected its first black mayor, Tom Bradley, who ruled over the city for twenty years and was able to forge seemingly unimaginable alliances amongst Blacks and Jews as well as labor and business reforms. The strife of Watts in 1965 and subsequent dissatisfaction generated Bradley’s success; preeminent California historian Kevin Starr commented, “I know of no one with a greater gift for reconciliation and healing.” As grisly as it sounds, in many ways the riot “worked.”

But the events in Watts did not come without consequences. In the same ways that the riot galvanized blacks and allowed them and other ethnic groups to put black leadership in place in LA, it also invigorated whites on a state level. The riot, along with other upheavals in 1967 and 1968, helped solidify suburban conservatism in the state as well as a law and order movement that sought to tame putatively unruly minorities. This social conservatism and tough on crime mentality were central to Ronald Reagan’s playbook. These moves allowed him to mosey into governorship of California from 1967 to 1975 and strut into the White House 1980-1988.

Watts wasn’t the main cause of Reagan’s success but it was unquestionably in the mind of white voters. Once Reagan became president, he gutted the remaining War on Poverty programs that were not already decimated by Nixon. Various government commissions investigated the causes of riots in the late 1960s. Although many of these causes were not novel news to poor blacks, the local and federal government’s lack of consistent commitment to post-Watts initiatives rendered their solutions ineffective. Today, unused commercial space and shoddily-planned residential housing in Watts abound. Martin Luther King, Jr. Community Hospital–the hospital that was created after the riots to address unmet health care needs in the region–closed in 2007 after a variety of management problems. It reopened last month and only time will tell if it will if will meet its mission. In hindsight, it is hard to not agree with Marquette Frye, who grumbled 20 years after his arrest, “after the revolt, they fed us pacification programs.” The uprising cannot be characterized as a categorical win or loss.

The Impasse of Race Relations

Such a stalemate is representative of the almost cha-cha slide-like nature of race relations. Progression then regression. People on the left maintain that although there have been some advancements, in the larger racial order of things, very little has changed. Their position is convincing. They are often armed with statistics that demonstrate the obnoxious and longitudinal persistence of segregation, racially disproportionate unemployment, and educational inequality.

Individuals on the right have a more sanguine view of things. They insist that race relations have transformed in the past half-century. They point to the explosion of the black middle-class, the proliferation of black multi-millionaires, diversified police bureaucracies, and a black president as incontrovertible evidence of racial progress. Some of these individuals might concede that racial bigotry exists–but this is usually understood as a “bad apple” problem. A cop who shoots a retreating black person or an ideologue who shoots up a black church are considered individual actors, but certainly not emblematic of systematic bias. In this camp’s view, systems and institutions have been fumigated of the odious racism that dominated the United States in your grandparents’ lifetime.

Watts illustrates how both sides can be right. Today, Watts sits in a larger county of Los Angeles that has one of the most diverse police forces in the country. Such diversity can reduce the possibility of racialized police violence but it is no surety. Bullets, particularly cop bullets, have no name and they can come from the gun of a white, black, Latino, or Asian American cop. But statistically speaking, they are likely to enter a black and brown body. For example, African Americans comprise 9% of the city’s population but account for 19% of police shootings and 31% of less serious use-of-force cases. So while police diversity offers the kinds of benefits that are missed by a media that is finally paying serious attention to police brutality, it is no racial charm.

Economic life amongst racial minorities also has the kind of booms and busts that support both sides of the progress debate. Since the early 1900s, there has always been a sizable black middle-class in the City of Angels. The movement (but not elimination) of barriers in Hollywood ostensibly increased the collective lot of black Angelinos. The same could be said about the under-discussed Latino middle-class, who has become an important bloc in city and county politics. Population growth and increasing median income suggest that such political power will be national soon.

But modest economic improvements cannot completely address black Los Angelinos’ disproportionately poor health outcomes, bleak employment prospects, and the hemorrhaging of their population due to increasing housing costs and discrimination. Indeed, the Housing Authority of Los Angeles County is fresh off of a $2 million dollar settlement related to housing discrimination against blacks and Latinos. Minorities challenged these matters of inequality in health, housing, and employment before the Watts uprisings; similar issues resonate today in big cities across the country.

Latinos, who now make up the majority of Watts residents, are not unscathed by seesawing racial and economic progress. In Los Angeles, the wage theft capital of the United States, Latinos–particularly women and the undocumented–are primary targets of non-payment or underpayment for services performed. They have the highest rate of income insufficiency (e.g. ability to have an adequate standard of living). Like their black counterparts, they also encounter housing affordability problems. Although their social circumstances are slightly different than African Americans, Latinos’ demands are not that different from black Los Angelinos pre and post-1965: dignified and reasonably-paid work, affordable housing, quality education, and freedom from police violence.

As the country continues to deal with racial strife, fatal police encounters, and dogged economic inequality, the Watts protests has instructional value for advocates of racial justice and their adversaries. For the former, short-term improvements can prove to be fruitful and can be an important respite from the daily onslaught of racial oppression. But racial activists must be mindful of the ways their conservative (and sometimes liberal) opponents can play the long-game and reverse hard-fought gains.

At the same time, opponents of racial progress better recognize that the oppressed will not sit by passively. Martin Luther King’s comments after the Watts uprisings are applicable to more recent protests. “The key error of both Negro and white leadership was in expecting the ghettos to stand still and in underestimating the deterioration that increasingly embittered its life.” Baltimore and Ferguson are no Watts, but that does not mean that people will be content with the two-steps forward, one-step back nature of American racial change.

— This feed and its contents are the property of The Huffington Post, and use is subject to our terms. It may be used for personal consumption, but may not be distributed on a website.

Taken from:

50 Years Later: Racial Outrage and the Importance of the 1965 Watts Uprising